Harriet Tubman had been married to John Tubman for five years when she escaped slavery in 1849. She came back for him — but he'd already found another partner.

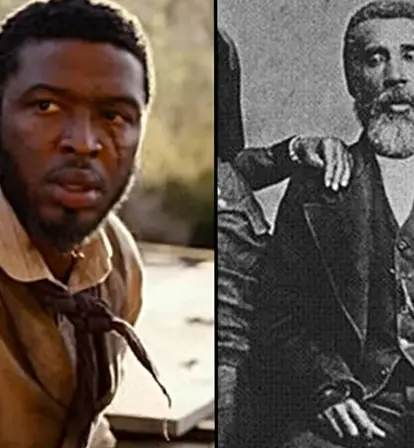

NY Daily NewsThis may be the only photograph of Harriet’s first husband, John Tubman (right), though its origins are unconfirmed.

John Tubman was a freeborn black man who became Harriet’s first husband. Their separation, brought on by Harriet’s will to gain her own freedom in the North, represents the divide between her old life as a slave and the strength of will she possessed in order to be free.

John Tubman Meets Harriet

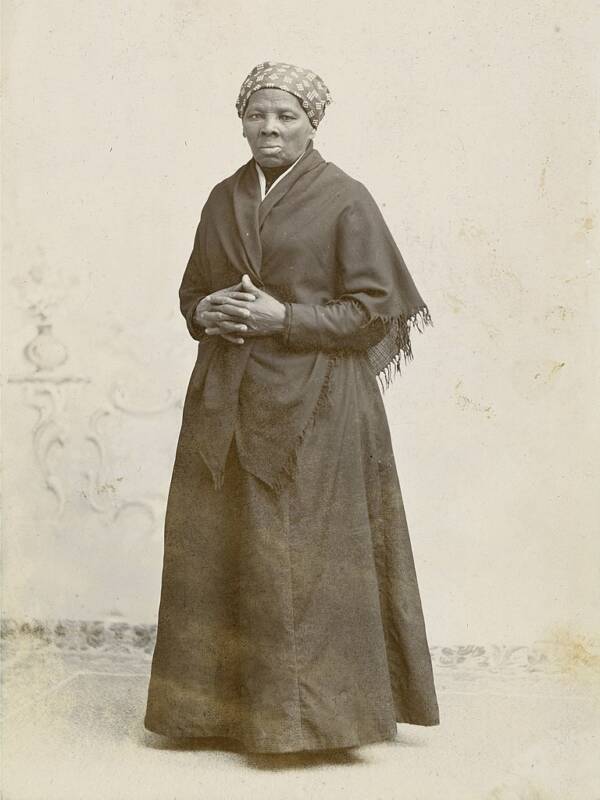

Library of CongressThis newly-discovered portrait of Harriet Tubman is from the 1860s, when Tubman was in her 40s. She married John Tubman when she was in her early 20s.

Harriet Tubman first met John Tubman in the early 1840s on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland, back when she still went by Amarinta “Minty” Ross. John Tubman had been born free and worked various temporary jobs.

Not much is known about their courtship but by all accounts the pair were very different from each other. Harriet was witty with an ebullient spirit and strong will. John Tubman, on the other hand, may have been brash, aloof, and even haughty at times.

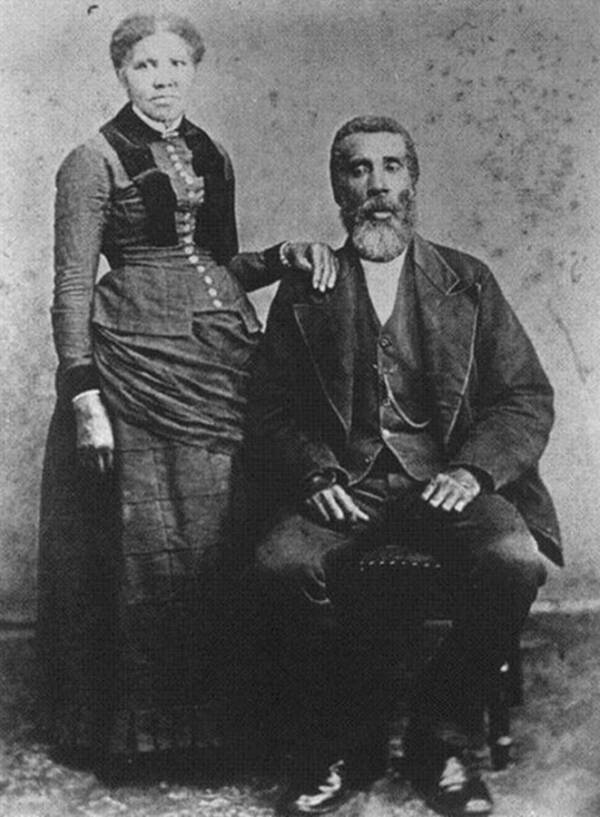

Library of CongressAn older portrait of Harriet Tubman, who became one of the most prominent ‘conductors’ of the Underground Railroad.

Unlike John, Harriet had been born into slavery. Marriages between free and enslaved blacks were not uncommon back then; by 1860, 49 percent of Maryland’s black population was free.

Still, marrying an enslaved person took away many rights from the free party. By law, children took their mother’s legal status; if John and Harriet were to have any children, their children would be enslaved like Harriet. Plus, their marriage would only be made legal if Harriet’s master, Edward Brodess, approved of it.

Yet in 1844, they married anyway. She was about 22 years old, he was a few years older.

Harriet Tubman Leaves Her Husband To Gain Her Freedom

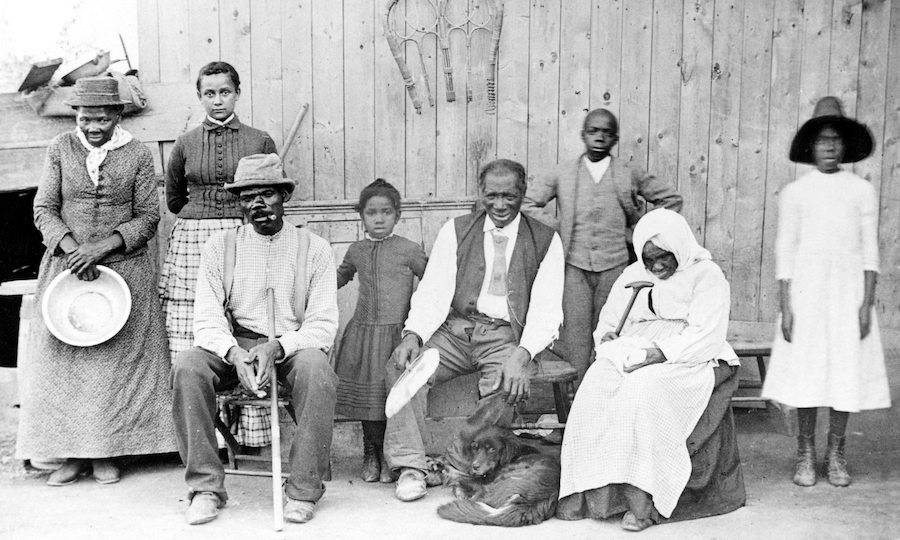

Wikimedia CommonsHarriet Tubman (left) with her friends and family, including her second husband, Nelson Davis (seated next to her) and their adoptive daughter, Gertie (standing behind him).

Harriet Tubman had suffered from narcolepsy and severe headaches since she was 13, when a white overseer threw a two-pound weight at her skull. Deeply religious, she believed her hazy dreams were premonitions from God.

The writer Sarah Hopkins Bradford incorporated Tubman’s ailment in a tale of John Tubman that has stuck to this day, despite a lack of other historical evidence. In Bradford’s second biography of Harriet, published in 1869, she paints John as a stubborn husband who writes off his wife’s visions as utter foolishness:

“Harriet was married at this time to a free negro, who not only did not trouble himself about her fears, but did his best to betray her, and bring her back after she escaped. She would start up at night with the cry, “Oh, dey’re comin’, dey’re comin’, I mus’ go!”

“Her husband called her a fool, and said she was like old Cudjo, who when a joke went round, never laughed till half an hour after everybody else got through, and so just as all danger was past she began to be frightened.”

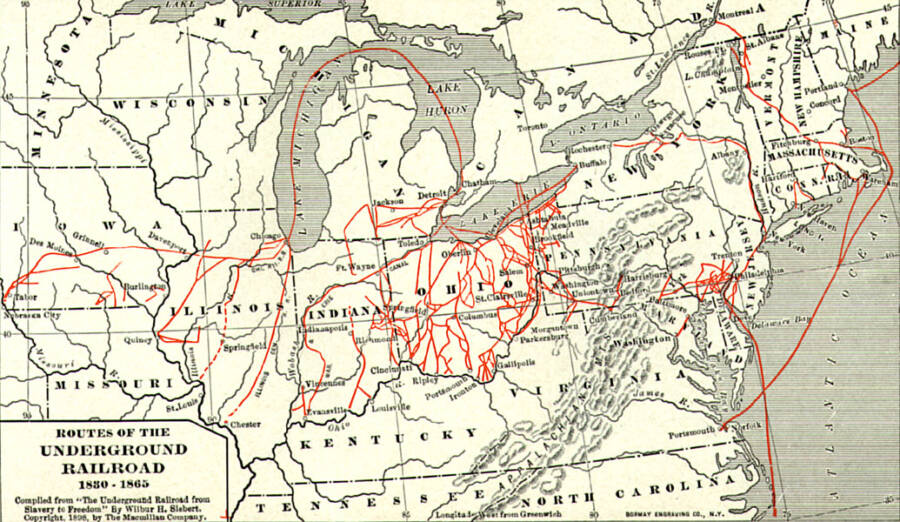

Wikimedia CommonsMap of the safe routes through the Underground Railroad network.

Later historical accounts have challenged this narrative.

In her 2004 biography Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero, Kate Clifford Larson maintains that John Tubman “has been treated quite unsympathetically in the various narratives of Harriet’s life.”

Bradford believes that John Tubman’s decision to marry her “appears the choice of a man deeply in love with or at least powerfully drawn to Harriet.” They may have even been trying to save enough money to buy Harriet’s freedom.

John Tubman probably wasn’t the devil that Bradford made him out to be. In fact, Bradford may have described him as such in order to sell more books; Harriet Tubman was, after all, one of the first women to make money from her own biography (she used the money to open a nursing home for indigent people of color in upstate New York).

Wikimedia CommonsDuring the Civil War, Harriet Tubman became the first woman in American history to lead an military raid.

But no matter how romantic their union was, their differences eventually broke them apart.

Harriet Tubman’s Escape To The Underground Railroad

Early in her life, young Harriet witnessed her sisters being sold off to other slave owners by their master, Edward Brodess. Her youngest brother almost suffered the same horrifying fate.

Wikimedia CommonsWhen her husband John Tubman refused to come with her to the free territory up north, Harriet left him behind.

The constant threat of being torn away from her family combined with the immense trauma brought on by life as a slave consumed Harriet’s psyche. It was clear that the only way to keep the family together for good — and save her own life — was to escape.

After a failed attempt to flee with her brothers, Harriet managed to escape on her own. She walked 90 miles to the free state of Pennsylvania, and then to Philadelphia, trekking under the dark of the night through treacherous and marshes.

Her owners placed a $100 bounty on her head, but her knowledge of Maryland’s wild areas and the abolitionists of the Underground Railroad helped her evade fugitive slave hunters.

Harriet tried to persuade John Tubman to come with her so that they could enjoy life as a free couple, but John refused. He did not share Harriet’s dreams of complete independence and even tried to dissuade her from her plans. But there was no question in Harriet’s mind about what she needed to do.

“There was one of two things I had a right to,” she later told Bradford, “liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have de oder.”

Harriet Tubman escaped her Bucktown, Maryland farm in the fall of 1849. She returned to Maryland the next year, to shepherd some of her friends and family to safety. The year after that, despite the risks, she returned to her former home to bring her husband up to Pennsylvania.

The Later Life Of John Tubman

But by 1851, John Tubman had taken another wife, and he refused to go up north with Harriet. Harriet was hurt by his betrayal and repeated refusals to go with her, but she let it go. Instead, she helped some 70 slaves reach freedom, becoming one of the most prolific conductors of the Underground Railroad.

In 1867, John Tubman was shot dead by a white man named Robert Vincent after a roadside quarrel. Tubman left behind a widow and four children, while Vincent was found not guilty of murder by an all-white jury.

Now that you’ve learned about Harriet Tubman’s first husband, John Tubman, take a look at 44 astounding photos of life before and after slavery. Then, meet John Brown, the white abolitionist who was executed after staging a failed raid to free black slaves.