In December 2001, U.S. forces captured an American Taliban fighter named John Walker Lindh in Afghanistan. Though he was soon thrown in prison, the story didn’t end there.

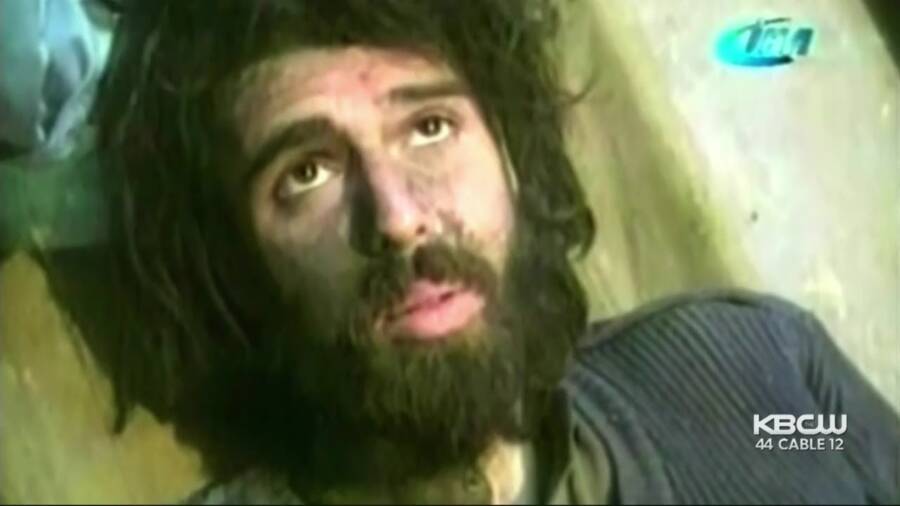

YouTube John Walker Lindh was captured with Taliban fighters in November 2001.

Shortly after the American invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, U.S. troops came across a shocking sight — an emaciated American in an allied prisoner of war camp. But 20-year-old John Walker Lindh wasn’t just in enemy territory. He was an American Taliban fighter.

By all accounts, Lindh had had an average American upbringing. He grew up in affluent Marin County, California, and studied hard at school. However, as other teenagers began to think about colleges, Lindh became increasingly fascinated with Islam.

Lindh’s fascination led him to travel to Afghanistan in the spring of 2001. There, he pledged himself to Taliban fighters and trained in al-Qaeda camps.

His discovery — just months after the 9/11 attacks — sparked fury throughout the United States. But who is John Walker Lindh, the so-called “American Taliban”?

Who Is John Walker Lindh?

Twenty years before al-Qaeda terrorists attacked on 9/11, John Walker Lindh came into the world at a Washington D.C. hospital.

He was born on Feb. 9, 1981, and named for Beatle singer John Lennon and 19th-century Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. Lindh spent his early years in the Maryland suburbs with his parents, Frank Lindh and Marilyn Walker, and two siblings.

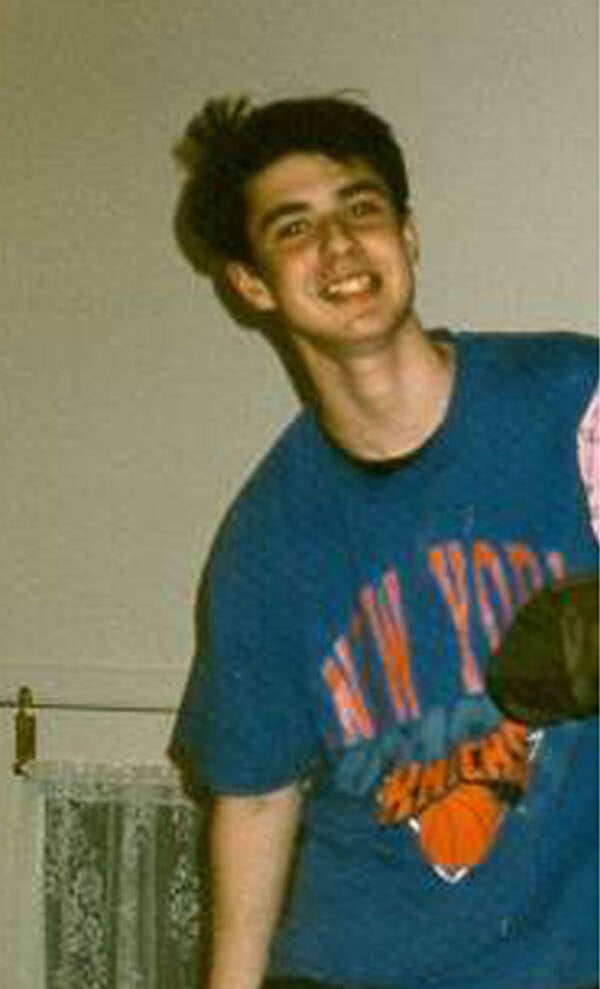

Lindh Family/Getty ImagesJohn Walker Lindh at 14, two years before he converted to Islam.

“He was a regular kid,” said Andrew Clernon, one of Lindh’s closest childhood friends. “Me and him were rambunctious. Our parents were always yelling at us for being loud and obnoxious.”

Lindh’s childhood — like many others — was jolted by a transcontinental move after his 10th birthday. He and his family settled in the affluent enclave of Marin County, California, in 1991, where Lindh learned to play the flute and told adults he wanted to help poor people when he grew up.

But when Lindh was 12, his life abruptly changed course after watching the film Malcolm X. He was enchanted by the movie’s discussion of Muslim pilgrims in Mecca and wanted to learn more about Islam.

“He wanted something pure, and he was definitely questing at an early age,” Frank Lindh recalled. “We encouraged him to look.”

As the years passed, Lindh’s exploration of Islam deepened. He asked questions in internet chat rooms and visited mosques in San Francisco. Soon, he grew a beard, wore an Islamic robe and cap, and asked friends and family to call him Suleyman.

But Lindh wanted more. At 16, he converted to Islam. A year later, in 1998, he set off for Yemen in hopes of learning Arabic and deepening his faith.

How A Kid From California Joined The Taliban

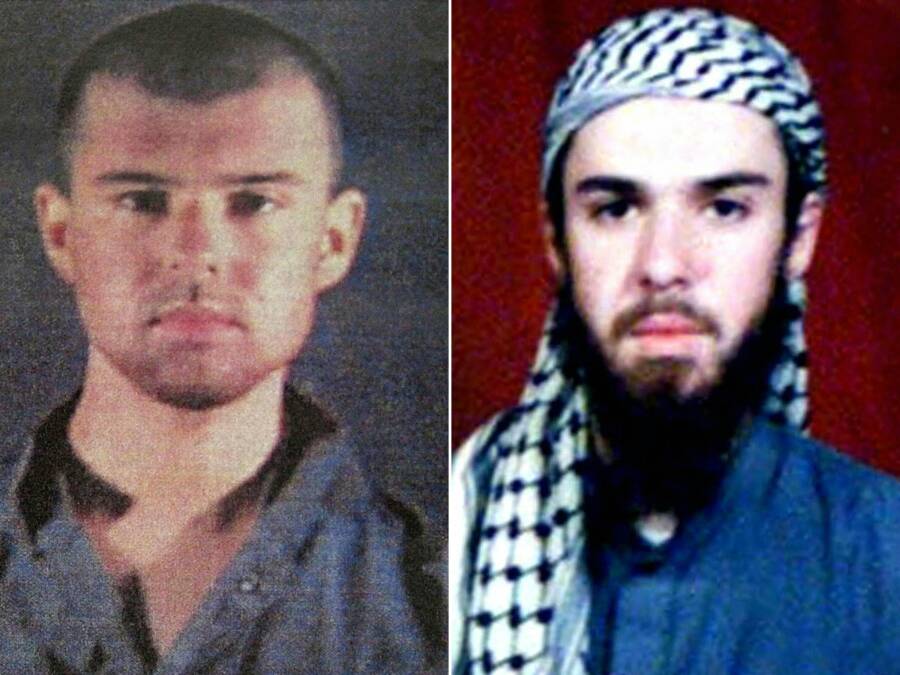

TARIQ MAHMOOD/AFP via Getty ImagesAs his interest in Islam deepend, John Walker Lindh began to dress in traditional Muslim clothing.

In Yemen, John Walker Lindh found nothing but disappointment. He returned to Marin County after 10 months abroad in 1999.

“[People in Yemen] weren’t as orthodox as he thought — they weren’t as strict on Islam as he thought,” explained Abdullah Nana, a friend Lindh had made at a San Francisco mosque.

But Lindh didn’t feel at home in California, either. In his absence, his parents had separated. After eight months, feeling lonely and unsettled, he decided to return to Yemen in February 2000. That October, he went to Pakistan to attend an Islamic school, or madrasah.

There, Lindh would find what he was looking for: the Taliban.

“I was a student in Pakistan, studying Islam,” Lindh later explained. “I came into contact with many people who were connected with the Taliban.

“[People] there, in general, have a great love for the Taliban. So I started to read some of the literature of the scholars, and my heart became attached to it. I wanted to help them one way or another.”

Meanwhile, Lindh’s parents had no idea what was happening. They last heard from their son in April 2001 when he said he was “moving somewhere cooler for the summer.”

In fact, Lindh had gone to an al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan. There, he would meet and make small talk with 9/11 mastermind Osama Bin Laden.

He also underwent training to learn about weapons, maps, explosives, and fighting on a battlefield. However, Lindh claims that he swore allegiance to jihad – holy war against Islam’s enemies — and not al-Qaeda. He also says that he refused to participate in operations against the United States or Israel.

But whether he knew it or not, such an operation was already afoot. On Sept. 11, 2001, al-Qaeda terrorists launched an attack in the United States.

The Discovery Of John Walker Lindh In Afghanistan

David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

President George W. Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld survey the damage at the Pentagon following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The al-Qaeda-led attack on 9/11 left almost 3,000 people dead. As the United States and its allies drew up plans to seek vengeance, they looked to the Taliban-led government in Afghanistan, which sheltered al-Qaeda terrorists.

“I said to the Taliban, turn them over, destroy the camps, free people you’re unjustly holding,” President George W. Bush said. “But they didn’t listen. They didn’t respond, and now they’re paying a price.”

On Oct. 7, 2001, the U.S. launched Operation Enduring Freedom. By that November, the American-backed Northern Alliance of Afghan rebel fighters had captured scores of Taliban fighters — including John Walker Lindh.

The Northern Alliance brought Lindh and Taliban members to a prison on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif. Two American CIA agents, Dave Tyson and Johnny “Mike” Spann, sorted through the prisoners, looking for al-Qaeda fighters. They could tell something was different about Lindh.

“Irish? Ireland?” Spann asked him. “Who brought you here?” Spann went on, snapping his fingers in Lindh’s face. “Wake up! Who brought you here? How did you get here? Hello?”

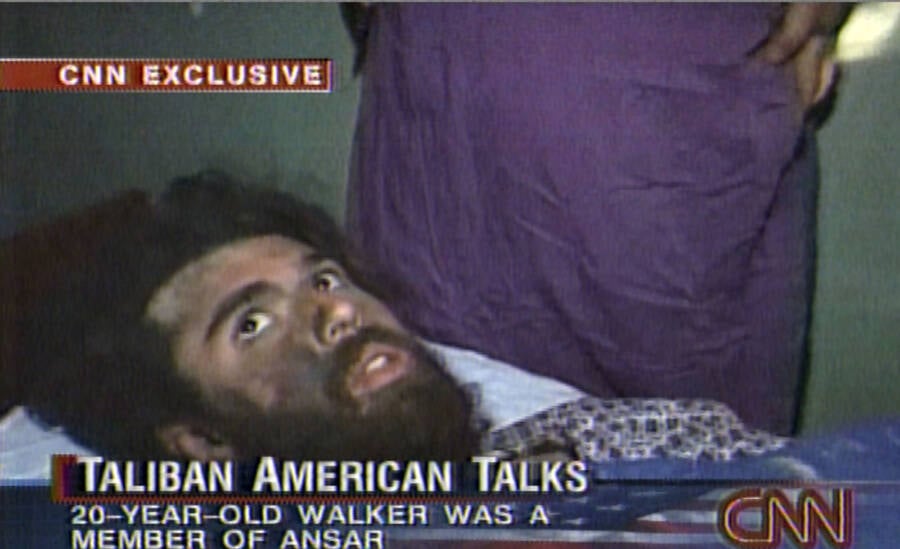

YouTubeA CNN correspondent stumbled across Lindh in an Afghanistan hospital, shocking Americans across the country.

Lindh didn’t say anything. He didn’t offer his name, and he didn’t tell Spann — though he may have known — that other fighters had grenades. Minutes later, the Taliban prisoners rose up and fought against their captors. Spann was killed. Lindh was shot in the leg.

Though some Taliban kept fighting, Lindh and others sought refuge in a basement. There, they huddled for seven days as explosions rocked the building. The Northern Alliance tried to flush them out with grenades, gasoline, and freezing water.

By the time they finally emerged — shaken but alive — American journalists had joined U.S. troops on the ground. Before long, a CNN camera crew broadcast John Walker Lindh’s image to his horrified fellow countrymen back home.

The Trial Of The ‘American Taliban’

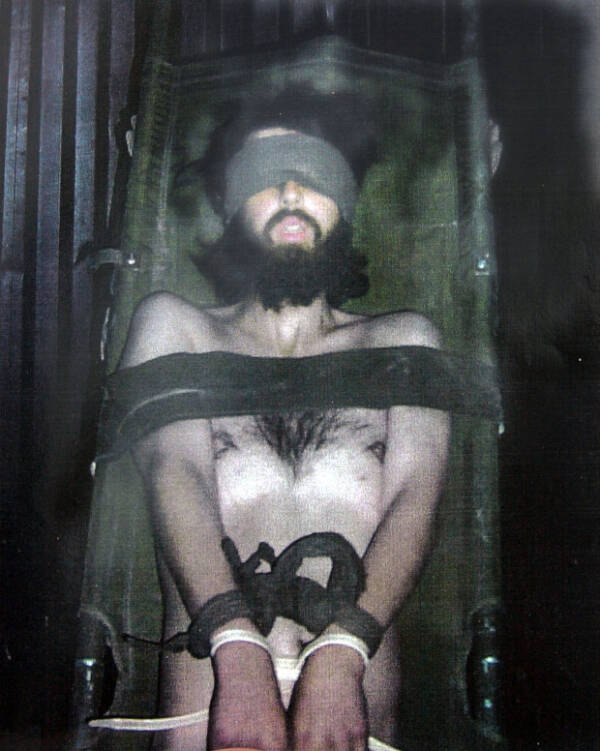

Wikimedia CommonsThough American officials deny it, Lindh’s father claims he was tortured.

For months, John Walker Lindh’s parents had struggled to track him down. Then they saw their son’s face on CNN.

“They couldn’t believe it,” said Bill Jones, a family friend. “He’s a good American kid. He must have got swept away in something, because he was on a mission of mercy.”

Others were less sympathetic to Lindh’s plight. Attorney General John Ashcroft avowed that “Americans who love their country do not dedicate themselves to killing Americans.” New York mayor Rudy Giuliani called for the death penalty. And Newsweek put Lindh on their December 2001 cover, labeling him as the “American Taliban.”

All the while, Lindh’s parents stood by his side.

“He must have been brainwashed,” Marilyn Walker told Newsweek. “He was isolated… When you’re young and impressionable, it’s easy to be led by charismatic people.”

“He’s not someone that would, that I would have ever imagined, could pick up a gun at all,” Frank Lindh insisted.

Meanwhile, Lindh underwent interrogation by American troops. His father claims that he was taunted, threatened, stripped naked, and bound with plastic restraints that caused permanent scars.

Though he’d already been convicted by the court of public opinion, Lindh was found guilty in 2002 for aiding the Taliban and carrying weapons. He was also accused of conspiring to kill Spann, which Lindh denied.

“I condemn terrorism on every level, unequivocally,” Lindh said at his sentencing.

“I made a mistake by joining the Taliban. I want the court to know, and I want the American people to know that had I realized then what I know now about the Taliban, I would never have joined them.”

In October 2002, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

A Terrorist Or A Victim?

Shawn Thew/AFP via Getty ImagesJohn Walker Lindh’s father, Frank Lindh (center), with attorney James Brosnahan (left) and Walker Lindh’s mother, Marilyn Walker (right), on 24 January, 2002.

For 17 years, John Walker Lindh lived a quiet existence behind bars in Terre Haute, Indiana. He spent his days reading the Quran and studying Islamic scholarships. The outrage surrounding his case died down, and — though the war in Afghanistan continued — the country began to move on.

But in 2019, Lindh left prison early due to good behavior. Suddenly, the questions that had peppered his discovery in 2001 shot back to the surface. Who was the “American Taliban”? And was he a threat?

Some would say yes. Lindh’s detractors pointed to statements he made in 2015 describing the Islamic State (ISIS) as “doing a spectacular job.”

Lindh also engaged in a correspondence with Atlantic journalist Graeme Wood that same year, in which he shrugged off Wood’s concerns about ISIS’s violence toward journalists.

“I understand your concerns about being killed or enslaved,” Lindh wrote. “However I believe that your apprehensions are misplaced.”

In addition, a 2017 report by the National Counterterrorism Center claimed that Lindh — without offering hard evidence — “continued to advocate for global jihad and to write and translate violent extremist texts.”

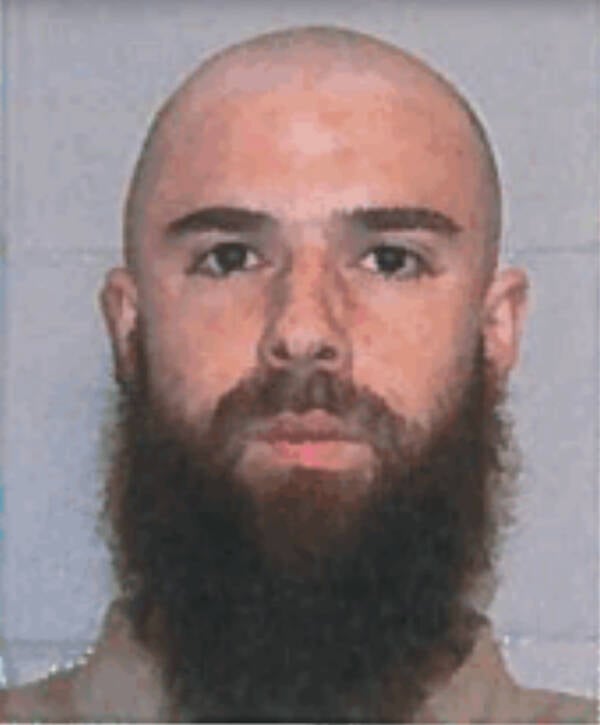

Federal Bureau of PrisonsJohn Walker Lindh pictured in 2017, two years before his release.

His release outraged Mike Spann’s family, who called it a “slap in the face,” and it rankled many on the right. President Donald Trump criticized the decision, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called it “deeply troubling.”

But John Walker Lindh’s supporters — including his family — tell a different story. To them, he’s a victim of an overzealous and shellshocked country.

“The U.S. has… been affected by post-traumatic shock,” Lindh’s father wrote in The Guardian in 2011. “I can find no other explanation for the barbaric mistreatment and continued detention of a gentle young man like John Lindh.”

And Lindh’s lawyer, James Brosnahan, once accused the U.S. government of having “brought up the cannon to shoot the mouse.”

But since his release, John Walker Lindh has stayed quiet. Under the terms of his probation, he cannot travel abroad or communicate with “known extremists.” Lindh must also undergo counseling and ask permission to use the Internet.

Though Showtime’s 2021 documentary Detainee 001 will attempt to unravel what happened to John Walker Lindh, his story — the true story — remains knowable only to him.

After reading about John Walker Lindh, the so-called “American Taliban,” look through these photos of 1960s Afghanistan before the Taliban took power. Or, explore these photos from the Soviet-Afghan war.