Terror and Counter-Terror

Wikimedia CommonsSurvivors gather the victims of a massacre of suspected Mau Mau fighters.

The British in the colony had limited options for dealing with the Mau Mau. The group had spent years organizing underground, and none of the captured fighters seemed willing or able to provide useful intelligence about the higher-ups. Informants were hard to come by, and those whose cover was blown died horribly before they could be moved to safety.

In this vacuum of information, and with nothing but their experiences and prejudices to guide them, the British developed a narrative of the Mau Mau as ignorant savages who acted without reason; merely a kind of brute animal that had gone wild, rather than as an emerging black political movement.

This led the authorities into a series of miscalculations that ultimately doomed their position in Kenya.

One of these miscalculations was to try using counter-terror to crush the popular support for the rebels. Mass arrests were followed by beatings and killings. Public whippings and hangings became commonplace events. Native, predominantly Kikuyu, women were fair game for any British or allied native rapist who could get at them.

Colonial administrators became obsessed with the secret Mau Mau oath, and they arrested tens of thousands of Kikuyu to learn who had taken it and who had not. Interrogators burned suspected Mau Mau, deprived them of food and water, and sometimes crushed their testicles with pliers or hammers.

Surprisingly few subjects confessed to having taken the oath, though whether this means the Mau Mau were doing worse things to turncoats or the British were arresting innocent people is not known even today.

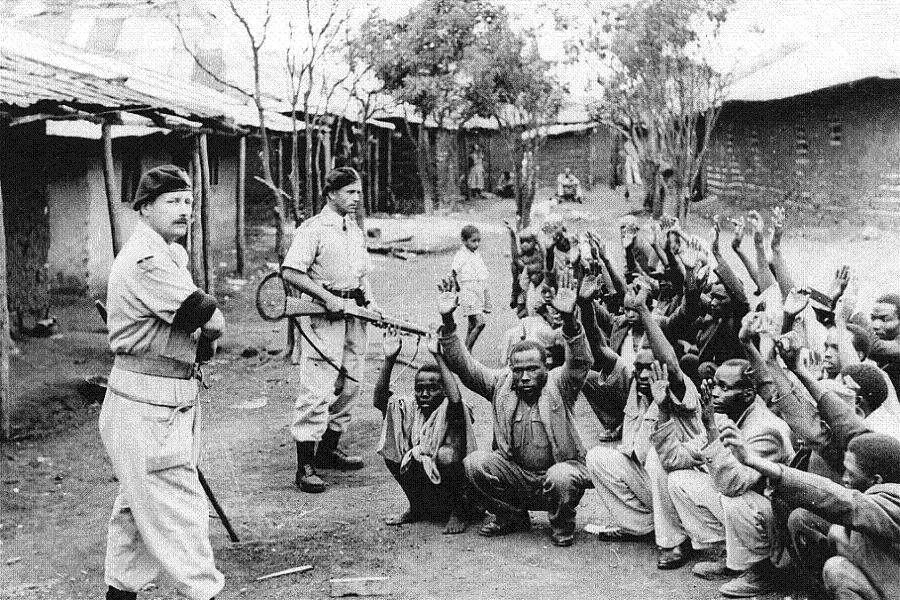

Mass Arrests, Public Executions

Wikimedia CommonsBritish Home Guard troops hold suspected rebels under guard during a mass arrest.

To facilitate the interrogations, the British built a network of concentration camps across the colony to hold suspected rebels. They divided internees into three classes, according to their degree of perceived cooperation.

The British sent Kikuyu who confessed to taking the Mau Mau oath and fully cooperated with investigators to relatively mild camps, where they were fed and housed as long as they were willing to help their captors. Resistant, or “Grey” prisoners went to harsher camps, while “Black” detainees, who flatly refused to cooperate at all, went to maximum security facilities for more starvation and torture.

In time, the camps expanded to hold hundreds of thousands of Kikuyu. On one single day in Nairobi, the British arrested something like 130,000 men and shipped them off to the camps, while another 170,000 women and children were sent to the reservations. Even some “loyal” Kikuyu were herded into the camps as the British policy seemed to shift into full-scale genocide.

Very little food made it to the prisoners in these camps, and hunger-related disease was rife. Tens of thousands of inmates had to use just two or three outbuildings for sanitary purposes, and Kikuyu women carried out the buildings’ waste atop their heads in large bowls for rinsing in nearby water.

Those Kikuyu lucky enough to not be arrested or shot on sight found themselves forcibly relocated to rural “villages,” ringed with barbed wire and trenches and patrolled by guards with orders to kill escapees.

Outside of the camps, reservations, and “villages,” the colonial government had resorted to open violence and routinely displayed the corpses of executed prisoners at crossroads as a warning. Even the Royal Air Force got involved, while British manpower was tied up in population centers.

In just 18 months, RAF Lincoln bombers dropped over 6 million bombs into Kenya’s forests to disrupt guerrilla activity. After one particularly gruesome massacre, the RAF dusted Kikuyu areas with photographs of mutilated women to intimidate the populace.

While initially set to expire in the summer of 1955, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill authorized the campaign’s indefinite continuation.