The U.S. government terrorized, outed, and fired at least 5,000 people suspected of being homosexuals during the Lavender Scare from 1947-1961.

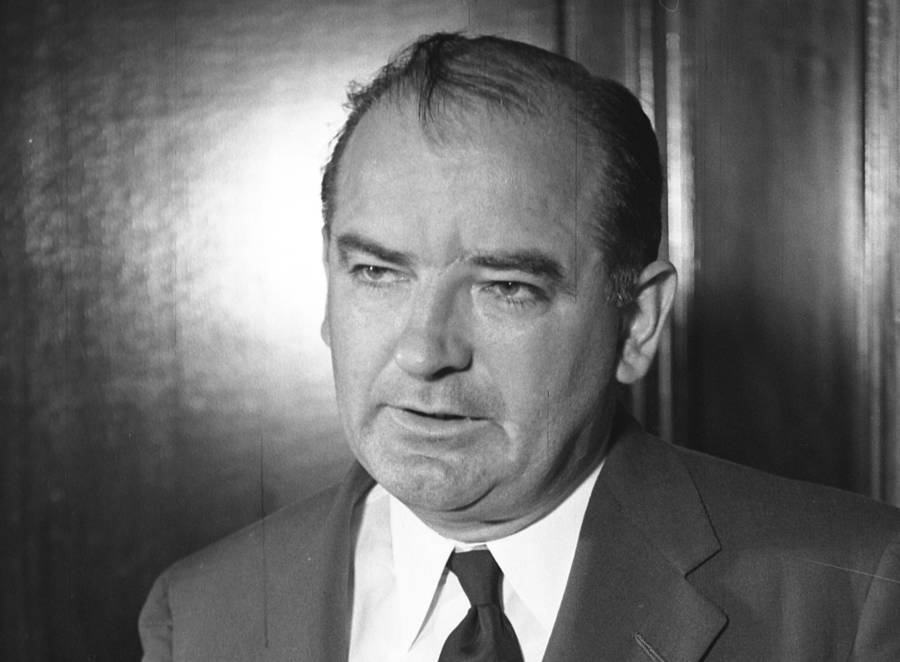

National ArchivesSen. Kenneth Wherry (left) and Sen. J. Lister Hill conducted the first congressional investigation into homosexuality in the federal workforce in 1950 as part of what’s become known as the Lavender Scare.

“These people are frightened to death,” said George Raines. A professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Raines was testifying before a U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating homosexuality among the federal government’s workforce in 1950. And the frightened people he was referring to were the men and women being targeted as part of a campaign now known as the Lavender Scare, the systematic removal of at least 5,000 suspected homosexuals from their government jobs.

Lasting from roughly 1947 to 1961, the Lavender Scare happened in conjunction with the Red Scare, the 1950s congressional witch hunt against communists spearheaded by Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

But while the Red Scare has been far more extensively documented, the Lavender Scare, according to the U.S. National Archives, lasted much longer and impacted many more people.

The Red Scare Gives Rise To The Lavender Scare

Library of CongressSen. Joseph McCarthy

In 1950, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy made his infamous speech in West Virginia during which he claimed to have a list of more than 200 employees of the State Department that were “known communists.” In doing so, he kicked the Red Scare into high gear and stoked fears that communists were infiltrating the U.S. government.

That same year, political rhetoric linking communism with homosexuality became prevalent.

McCarthy and other government employees made statements alleging that gay men and lesbians were either as dangerous or more dangerous than communists because they were easily susceptible to blackmail. At a time when homosexuality wasn’t widely accepted, McCarthy claimed that in order for a homosexual to keep their sexual orientation private, they would reveal government secrets to those who were threatening to out them.

Thus the Lavender Scare (its name taken from the fact that Sen. Everett Dirksen referred to gay men as “lavender lads” at the time) became inextricably linked with the Red Scare.

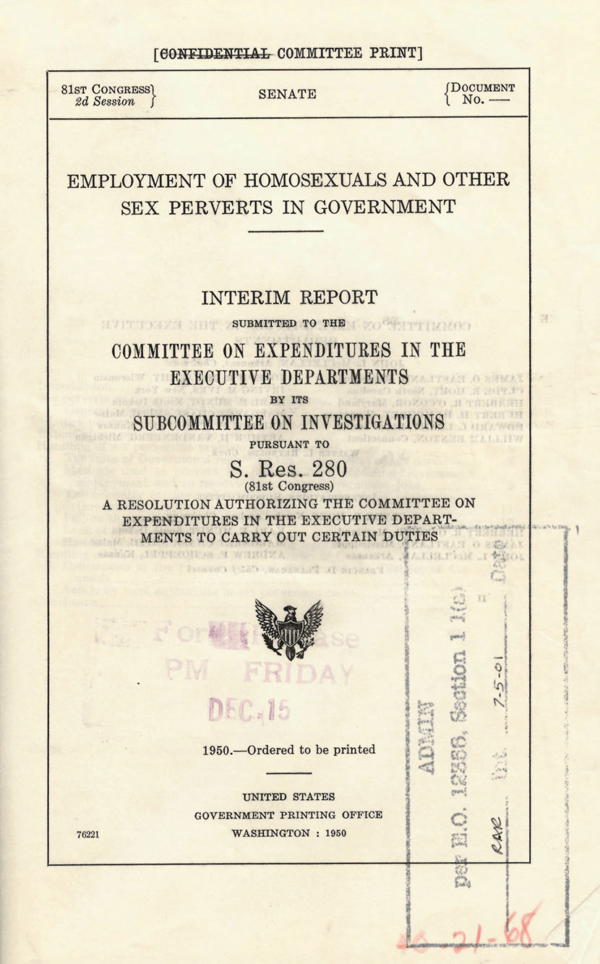

National ArchivesThe Hoey committee report.

The Lavender Scare came to national attention in its own right largely thanks to the 1950 Senate subcommittee (known as the Hoey committee after its chairman, Sen. Clyde Hoey) before which George Raines testified. By the time they released their report on Dec. 15, 1950, they’d concluded that the State Department was overrun with “sex perverts,” namely homosexuals.

Earlier that year, another small Senate subcommittee led by Sen. Kenneth Wherry and Sen. J. Lister Hill had claimed that there were at least 3,000 homosexuals working in the State Department.

With these committees stoking fears about homosexuals infiltrating the government, the State Department fired about 600 employees on so-called morals charges by the end of 1950. But the worst was yet to come.

Executive Order 10450

National ArchivesDwight D. Eisenhower

More so even than the Senate subcommittees of 1950, what truly solidified the Lavender Scare as an all-out witch hunt was Executive Order 10450. Signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, it set security standards for federal employment. And because gay people were seen as a security threat, the executive order barred homosexuals from working in the federal government.

Several actions paved the way for Executive Order 10450. In 1947, federal law enforcement initiated a “Sex Perversion Elimination Program” designed to arrest and intimidate gay men in Washington, D.C.

The following year, Congress passed an act “for the treatment of sexual psychopaths” that allowed people who acted on same-sex impulses to be arrested and classified as mentally ill.

But after Executive Order 10450 went into effect, anti-gay action reached new heights. Estimates claim that at least 5,000 suspected homosexuals were fired from their positions with the government, military, or even government-affiliated private contractors between approximately 1947 and 1961.

And it wasn’t just jobs that were lost. Some people who couldn’t cope with the terror of the Lavender Scare wound up committing suicide (with the whole thing covered up by federal agents, no less).

YouTubeNewspaper report on the death of Andrew Ference.

One State Department employee, Andrew Ference, was on assignment in Paris when he confessed that he was gay to federal agents who interrogated him over the course of two days in August 1954. The agents forced Ference’s resignation and less than a week later, he killed himself with gas from his kitchen stove.

The official report on his death listed the cause as “inactive lung lesion.” Ference’s family didn’t learn the true cause until two years after he died.

Resistance To The Lavender Scare

While government pressure on suspected homosexuals was fierce, several resistance groups fought back against the Lavender Scare. Perhaps the most famous gay activist in question, Frank Kameny was an astronomer who was fired by the Army Map Service in 1957 because he had been arrested a year earlier for “consensual contact” with another man.

However, Kameny fought back and filed an appeal that took his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

Although that appeal failed in 1961, the case raised awareness and Kameny went on to help found the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C. in order to fight anti-gay discrimination. The group even protested outside the White House in 1965 in what’s sometimes called the first gay rights demonstration in American history (above).

The Legacy Of The Lavender Scare

Wikimedia CommonsObama signs the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act of 2010 into law.

Despite resistance efforts and the 1956 Supreme Court ruling that limited discriminatory firings to federal employees directly involved with matters of national security, the Lavender Scare persisted well after the Red Scare faded away.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the first real progress was made in reversing the damage of the Lavender Scare. In 1973, a federal judge ruled that sexual orientation alone wasn’t grounds for termination from federal employment. In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced that gay people could no longer be barred from federal employment based on sexuality.

Executive Order 10450 nevertheless stayed on the books until 1995, when President Bill Clinton rescinded it. By the time it was rescinded, more than 10,000 men and women had been forced to leave their jobs. Clinton, in turn, put in place the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for gay people in the military, which was itself repealed in 2011.

It wasn’t until January 2017 that the State Department formally apologized for the Lavender Scare in a statement issued by the then Secretary of State John Kerry.

“In the past—as far back as the 1940s, but continuing for decades—the Department of State was among many public and private employers that discriminated against employees and job applicants on the basis of perceived sexual orientation, forcing some employees to resign or refusing to hire certain applicants in the first place,” Kerry wrote.

“These actions were wrong then, just as they would be wrong today.”

After this look at the Lavender Scare, take a look at some of the most powerful images from the early days of the gay rights movement. Then, discover the story of David Kirby, the 1980s gay activist whose iconic deathbed photograph put a face on the AIDS crisis.