While Lee Kuan Yew ushered in an era of wealth for Singapore, it came it a high cost. Open markets do not equal open societies.

Flowers left in memorial of Lee Kuan Yew following his death in March 2015. Source: Flickr

In 1989, the Chinese government massacred hundreds of protesters who had gathered at Tiananmen Square. A few years after the slaughter in Beijing, Singaporean political leader Lee Kuan Yew told an interviewer, “If you believe there is going to be a revolution of some sort in China for democracy, you are wrong. Where are the students of Tiananmen now? They are irrelevant.”

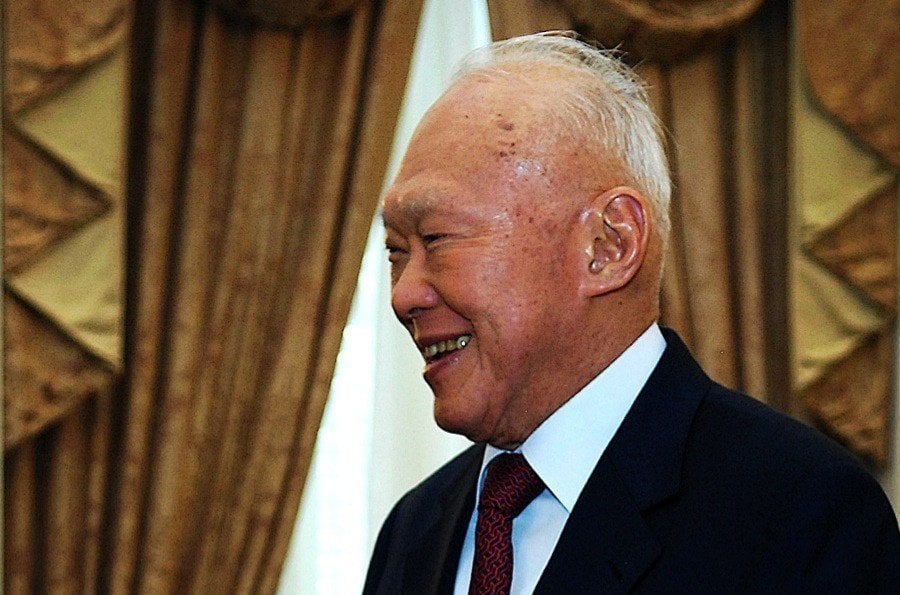

Lee Kuan Yew, who recently died at the age of 91, was Singapore’s first Prime Minister. He held that office from 1959 until 1990 and continued to preside in various high-level positions until his death in March of 2015. Singapore experienced a dramatic transformation over the half-century of Lee’s life in public office. In Asia and around the world, his public tenure is often praised as an economic and political model that developing countries should follow.

Lee’s model, however, relied on suppression of speech, the jailing of political opposition, and frequent use of court systems to financially cripple his critics. In many ways, Lee got lucky. Singapore, more of a city-state than a country, sits at one of the most important crossroads of international trade. It has succeeded in spite of its Prime Minister’s heavy-handed leadership, and it is entirely plausible that another leader could have charted a course to equally impressive economic success while avoiding human rights violations. Lee was an outlier, not an exemplar.

The island-nation of Singapore is home to 5.4 million people. Source: Flickr

The reason many look to Lee for guidance is that Singapore did achieve remarkable economic development during his time in office. His administration emphasized economic openness, ease of doing business, and international trade, and Singapore benefitted tremendously from its strategic location on the Strait of Malacca, one of the most important waterways for Chinese trade with the rest of the world.

In the last half-century, the small country saw its GDP per capita grow astonishingly. From less than $500 annually in 1960, GDP per capita grew to over $55,000 annually in 2013, making Singapore the third (or fourth, depending on the ranking) wealthiest country in the world by that measure.

Still, despite his country’s rapid economic success, Lee’s legacy is stained with significant abuses of power. He once cited the British colonial empire and the Japanese army of World War II as inspirations for how to govern. He said they knew how to “dominate the people.” While he opened up the economy, Lee only partially opened up the political process to his country’s citizens. In Singapore, as in China as of late, open markets have not coincided with an open society.

Lee Kuan Yew in Berlin, 1979. Source: Quartz

Lee’s abuses of power began in earnest in the 1960s when he jailed large numbers of political opponents in the name of “national security.” Another of Lee’s favorite tactics was to sue critics for defamation. The courts, filled with Lee loyalists, almost always ruled in his favor and imposed withering fines on his enemies. These Hugo Chávez-style tactics have kept Lee’s Political Action Party (PAP) in uninterrupted control of the government since 1968.

Lee took a similar approach to journalists, and a large part of his legacy is that, to this day, Singapore does not have a free press. Non-profit watchdog groups consistently classify Singapore as one of the world’s worst performers for press freedom. Freedom House ranks Singapore as 152nd out of 197 countries in their index, and Reporters Without Borders scores Singapore as 153rd out of 179 countries, below such serious human rights violators as Venezuela and Myanmar.

The worst part of Lee’s legacy is that many developing countries continue to look to his governing style as a model for their own ambitions of rapid economic development. Of course, Ethiopia, Vietnam, China, and other countries looking to emulate Lee can never hope to reproduce the conditions of small, strategically-located Singapore. What they can appropriate is Prime Minister Lee’s tendency to restrict the speech of his political opponents, journalists, and citizens.

For truly harmonious societies to emerge in developing countries, leaders will more likely have to abandon rather than embrace Lee’s model in the future. Many Singaporeans have been trying to do so themselves for decades, even if the government’s oppressive tactics have often silenced them. It is unclear whether they will have greater success now that the so-called benevolent authoritarian is gone.