It’s often been said that much of the United States’ history has been “whitewashed”: That school history textbooks focus primarily — and unduly — on the achievements of Caucasians, and more specifically, Caucasian men.

Critics say that this lack of diversity not only does a disservice to American students who deserve a complete portrait of their nation’s history — it’s downright inaccurate.

Of course, no one can undo centuries of erasure in one fell swoop. What we can do, however, is highlight the stories of under-acknowledged people whose achievements should make them household names. Here are five of those people:

Susan La Flesche Picotte

Biography

Historians generally regard Susan La Flesche Picotte as the first Native American physician, and one who devoted her life equally to study and activism.

Born on Nebraska’s Omaha Indian Reservation on June 17, 1865, Picotte’s early life was informed by a period of flux and hardship for Native Americans. At this point in time, the federal government had started relocating Native Americans to reservations — typically land that no one wanted — where residents would often become mired in poverty and disease.

In spite of these conditions, Picotte excelled at school and pursued an education at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, one of the only institutes of higher education that admitted women at the time.

After she graduated (and received top marks, no less), Picotte returned to the reservation, where she served as the community’s officially appointed physician. There, she would care for over 1,000 patients of various races, earning only $500 a year — ten times less than a U.S. Army or Navy Doctor.

While treating her patients, Picotte observed that many of the patients’ conditions could be avoided had they taken certain measures in advance. One measure, Picotte concluded, was proper hygiene. Thus, Picotte became an early advocate of preventative medicine, which while commonplace today was a relative rarity back then.

Picotte’s work on the reservation eventually led her to found her own hospital, and later lead her to Washington, D.C., where she called on the U.S. government to make improvements in Native Americans’ legal status and citizenship, and provide them legal protection against land fraud and speculation.

While Picotte devoted the majority of her life to improving those of others, her own life was quite short. The doctor and activist died at the age of 50, most likely to bone cancer.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Wikimedia Commons

Although her name doesn’t appear alongside figures like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer’s efforts in the civil rights movement are surely worthy of widespread recognition.

Born in 1917 in Montgomery County, Mississippi, Hamer’s early life would shape much of her future endeavors in social justice. The youngest of 20 children, Hamer dropped out of school at age 12 to pick cotton and support her family — a decision which would give her the kind of education a classroom simply can’t provide.

Hamer found her true purpose, however, in 1961, when a non-consensual hysterectomy left Hamer infertile. At the time, the forced sterilization of African-American women against their will — usually when they were in the hospital for minor, unrelated surgeries — was common.

After experiencing the event herself, Hamer worked to draw public attention to the practice, which she called the “Mississippi appendectomy.”

This trauma — along with other harrowing experiences she endured as a black woman in the South of the 1960s — prompted Hamer to attend meetings with local political activists. Throughout the course of these meetings, Hamer and her husband met prominent civil rights activists, and Hamer realized that she wanted to spend her life working alongside them.

As an activist, Hamer first set her sights on the issue of voting rights. At the time, individual states — particularly those in the South — passed voting registration requirements (such as literacy tests, property ownership requirements and payment of poll taxes) that had the effect of preventing African-Americans from registering to vote, thus rendering them second-class citizens.

Alongside 17 other African-Americans, Hamer traveled to Indianola, Mississippi to register to vote — a move which would cost Hamer her job at the plantation on which she worked. That experience, while devastating, only furthered her resolve.

As Hamer later said of that event, “I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared — but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

Undeterred, Hamer went on to organize demonstrations in order to grant full voting rights to African-Americans, an act which would see Hamer arrested, beaten, harassed, and even shot. In fact, Hamer once suffered a beating so severe that it inflicted permanent damage upon her kidneys.

Despite the consistent and sometimes potentially fatal adversity Hamer faced, she did not succumb to the status quo, and instead helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which formally challenged it.

At the time, the Mississippi Democratic Party’s platform dictated that only whites could participate in the party, despite the fact that blacks made up nearly half of the state’s population. The non-exclusionary MFDP ran alongside the Democratic Party, and soon had over 80,000 members — black and white.

In 1964, the MFDP sent a handful of delegates to that year’s Democratic convention, demanding that it be treated as the only democratically-constituted delegation from Mississippi. A convention compromise offered the MFDP two seats, which the party refused.

“We didn’t come all this way for no two seats, ’cause all of us is tired,” Hamer said.

After the convention, Hamer delivered an impassioned speech about voting rights — one which, despite President Lyndon Johnson’s attempts to keep her from speaking (and to keep others from viewing Hamer’s speech on TV) would lead to a flurry of calls for equal voting rights for all.

The next year — due in no small part to Hamer’s efforts — Johnson convinced Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which prevented states like Mississippi from passing or imposing discriminatory voting registration requirements.

Despite being diagnosed with breast cancer, Hamer continued her fight for equal rights up until her death in 1977 at the age of 59.

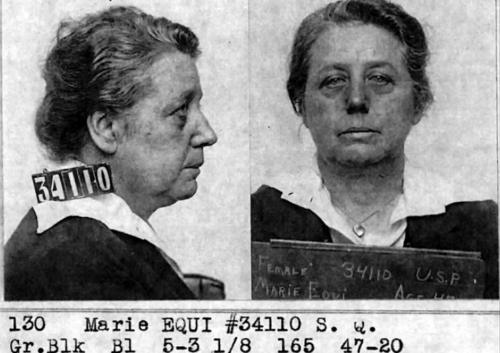

Marie Equi

Daily Emerald

While a contemporary of Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, history has buried many of Marie Equi’s contributions to women’s health (including birth control and access to abortion). This historical erasure may stem from the fact that — besides being a rebel physician of her time — Equi was also a lesbian.

Born to immigrant parents, Equi grew up in Massachusetts, where existing social mores may have given her some insight into her sexuality early on in life. At the time, professional and wealthy women in New England would occasionally engage in same-sex relationships known as “Boston Marriages,” where the couple would live under the same roof to varying degrees of emotional and sexual intimacy.

Equi eventually left Massachusetts for Portland, Oregon, where in 1905 she founded her own practice and became one of just 60 female physicians in the state. Shortly thereafter, Equi began providing abortions — and to any woman, regardless of age, race, or social status (though she did admit to charging wealthy women more, in order to help cover the costs of running her practice). This tiered payment scheme offered an early model of the “sliding scale,” which many private medical practitioners employ today.

Unlike many of her colleagues, Equi managed to avoid arrest for providing abortions. She did, however, get into trouble for offering birth control and disseminating information about it to women in her practice and community.

It was during this time Equi met Margaret Sanger, with whom she was arrested in 1916. Equi continued to write to Sanger for many years following their encounter, and did not attempt to conceal her infatuation with her.

Equi did have a partner of her own, Harriet Speckart. Together, the two adopted a baby. While that may merely raise some eyebrows today, at the turn of the 20th century same-sex adoption was virtually unheard of — and often punishable by law.

Furthermore, Equi did not advocate for women alone. She also lobbied for the eight-hour workday, and opposed U.S. involvement in World War I, saying that it was little more than an imperial land grab.

Her opposition to the war — Equi famously unfurled a banner in Portland that said “Prepare to die, workingmen, JP Morgan & Co. want preparedness for profit” — ultimately rendered her a “security threat” in the eyes of the federal government, and in 1918, she was convicted Equi of espionage.

Originally sentenced to three years in San Quentin prison, President Woodrow Wilson lifted her sentence to just over a year — which Equi didn’t serve in its entirety due to good behavior.

Although Equi continued to practice medicine and advocate well into old age, health problems certainly did slow her down. When she died, at the age of 80 in 1952, her obituary ran in newspapers across the country.

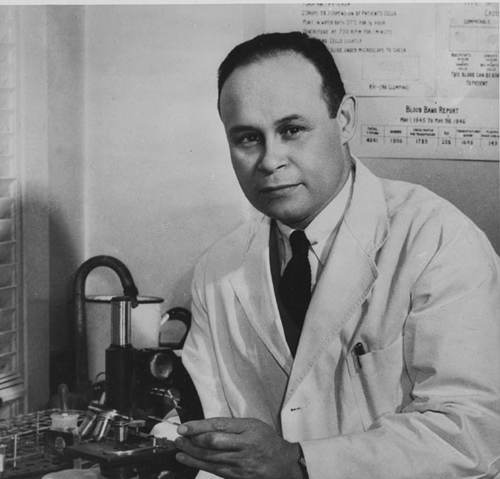

Charles R. Drew

Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t just female physicians like Marie Equi whom history often forgets, but also African-Americans like Charles Drew.

A physician and medical researcher during World War II, Drew’s development of the blood bank not only changed the course of the war, but human history.

Drew was born to a middle-class family in Washington, D.C., which gave him the opportunity to pursue a college degree. In 1933, after receiving his medical degree from McGill University in Montreal, Drew returned to the States to train as a surgeon, and became the first African-American physician appointed to the American Board of Surgery.

A few years later, Drew added another “first” to his belt when he became the first African-American to receive a graduate degree from Columbia University — which he completed, in Medical Science, just prior to the outbreak of WWII.

After the carnage of World War I, which left 17 million dead and 20 million wounded, the race to advance battlefield medicine was on, and the United States recruited Drew to help win it. Specifically, the idea of blood banking — storing blood in large amounts for future transfusions — needed refinement before the U.S. could put it into practice.

The States also expressed a need to transport blood to Great Britain, where the greatest threat existed at the beginning of World War II. Drew led the collection side of this program, which was based in New York City, and came up with the strategy and method which would enable all donations occur to at a central location.

As Drew continued to develop methods that would refine this process, he created what we now call the American Red Cross Blood Bank. If you’ve ever donated or received blood, you have Drew to thank for that.

Despite Drew’s game-changing work, he ultimately resigned from his post after legislation passed that prohibited people of color from donating blood. And in 1950, a fatal car accident closed the door on whatever else Drew may have achieved in his life.

Following the car accident, a myth circulated which said that Drew died because doctors refused to give him a blood transfusion on the basis of his skin color. But those who were with him and survived said that this wasn’t true: In fact, Drew’s injuries were so extensive that, despite the fact that he did receive emergency medical attention (which many African-Americans would have been refused at the time), he could not have been saved.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham

Wikimedia Commons

Even though Rosa Parks became the poster woman of the fight to end racial segregation, many women preceded her. One woman, Elizabeth Jennings Graham, led the fight against transportation segregation as early as 1854 — a full 100 years before Rosa Parks.

In 1830, Graham was born to two prominent New York residents: Her father, a free black man, was the first known patent holder of his race in U.S. history and her mother served as a speaker and member of New York City’s literary society.

Graham’s father had bought her mother’s freedom from slavery, so when Graham was born, she too was free. Graham then received an education and became a teacher, and spent a lot of time with her church community, where she played the organ.

It was on her way to church for Sunday service in July 1854 that Graham became part of history: Running late, Graham ran to catch a streetcar and boarded it, only for the conductor to tell her to exit.

At the time, horse-drawn streetcars offered a popular mode of transportation within American cities, and like the buses that would follow them, they were racially segregated. This could happen, at least in part, because the rails were privately owned and operated.

As the New York Tribune recounted of the event:

[Graham] got upon one of the Company’s cars last summer, on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered, but she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.

As word spread about Graham’s incident, the call to end segregated transport in New York gained traction — and Graham became the most-cited example in making the case for it. This notoriety came at least partially because she actually sued the owner of the streetcar company — and had the representation of a young lawyer named Chester A. Arthur, who would later become President of the United States.

Graham won the suit, with the judge declaring that “Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence,” and awarding her $250 in damages (around $10,000 today).

This case law ultimately proved instrumental in the desegregation of New York City public transport ten years later.

Graham, however, was all but forgotten: Very little is known about her life following the lawsuit’s end. Historians do note, however, that Graham remained active in the Civil Rights movement until the New York City Draft Riots of 1863, during which time her only child became ill and died.

After his death, Graham and her husband left the city for four years — at which point her husband died. Toward the end of her life, Graham returned to New York City and started a neighborhood school house for black children. It operated until her death in 1901.

Next, read up on six brilliant female scientists who never got the recognition they deserved. Then, get to know the female civil rights leaders you didn’t learn about in school.