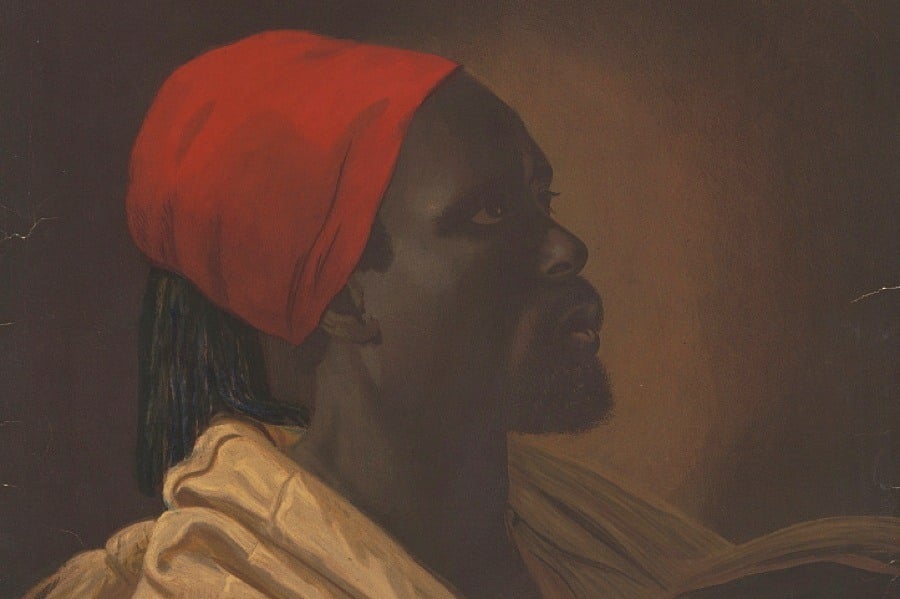

The heroic story of Toussaint Louverture, who brought himself and his people from slavery to freedom.

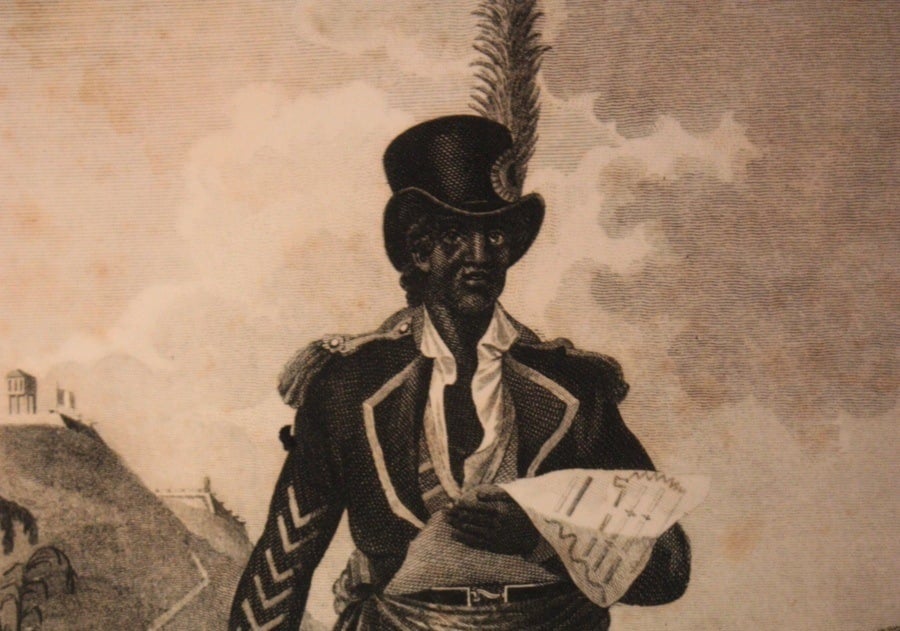

Library of CongressToussaint Louverture.

A typical 18th-century plantation employed hundreds of slaves who worked 16 to 18-hour days in all kinds of weather. Rations were minimal and punishments were brutal. The largest, most profitable European slave colony was French-controlled Saint-Domingue, the western part of contemporary Haiti (the eastern part, Santo Domingo, was Spanish).

Famed economist Adam Smith described Saint-Domingue as “the most important of the sugar colonies of the Caribbean,” and largely due to trade with the newly independent United States, production in Saint-Domingue nearly doubled between 1783 and 1789.

The French colonial powers thus made sure to maintain control over the more than half a million black slaves in Saint-Domingue — and to that end, they employed horrific violence.

In their book Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492-1971, Robert and Nancy Heinl quote Vastey, a slave who described the crimes against the slaves of Saint-Domingue:

“Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive…. flayed them with the Lash…. lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes…thrown them into boiling caldrons of cane syrup…put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss…consigned these miserable blacks to man-eating dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and [dagger]?”

Despite — and perhaps because of — such violence, Saint-Domingue saw a steady succession of slave revolts beginning as early as 1679. This would continue into the 18th century when in the last years before the French Revolution (1785-1789), the French brought 150,000 slaves to Saint-Domingue to keep up with the region’s explosive economic growth.

This growing number of slaves grew angrier at the conditions they faced, and colonial powers took note of it. As the Marquis de Rouvray wrote in 1783: “We are treading on loaded barrels of gunpowder.”

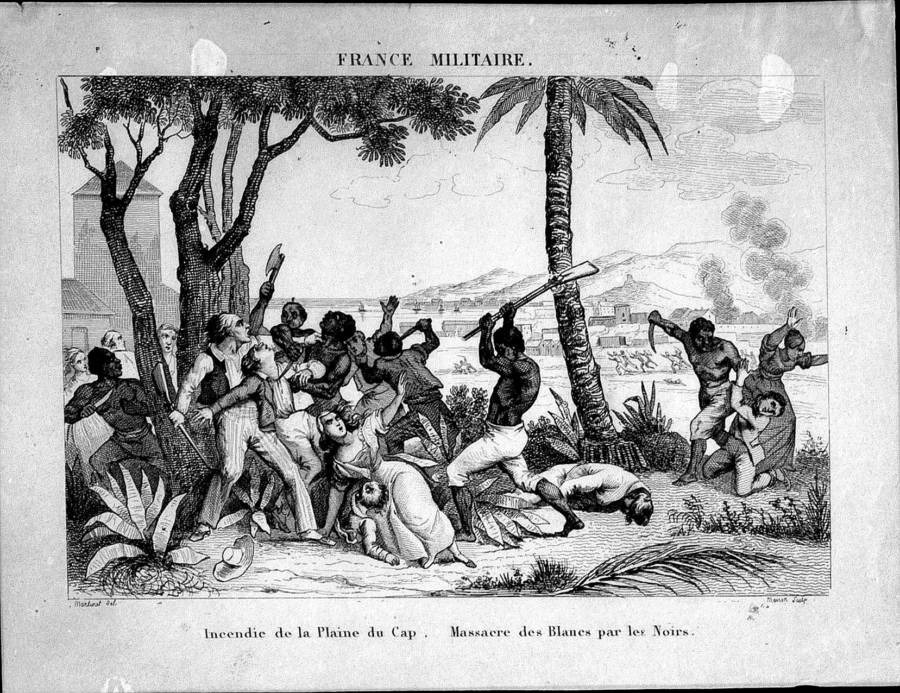

Wikimedia Commons“Burning of the Plaine du Cap – Massacre of whites by the blacks.” A French military rendering of the August 1791 slave revolt.

On the night of August 21, 1791, the barrels exploded. The slave revolt spread fast, giving rise to numerous armed rebel bands. At first, the African rebels did not fight for full emancipation; in fact, most generals sought only freedom for themselves and their followers and better conditions for other slaves.

Then, two factors transformed the conflict into something greater and further reaching: the French government’s desperate need for allies, and the leadership of one slave named Toussaint Louverture.

The French Revolution And Counter-Revolution

By 1793, the French revolution had fallen in the hands of the Jacobins, among the most radical of the revolutionary groups. French Royalists, the British, and the Spanish all fought against the Jacobins, and eventually, the revolution would yield to more moderate leadership, and then to the reign of the autocratic emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821).

In spite of its maxim of “liberté, égalité, and fraternité,” it was only in the Jacobin government’s dying moments (February 1794) that it abolished slavery. And this only happened because three abolitionists from Saint-Domingue — a white colonist, a mulatto, and a black freedman — managed to make it to Paris and demand it. In the throes of revolution and in need of support, the fiery Jacobins granted the petition for abolition without debate.

Their acquiescence proved fruitful: the support of the 500,000 slaves and the economic base they represented in Saint-Domingue allowed the Jacobins to continue fighting their other enemies in the revolution. And the most important leader among this population of slaves would soon prove to be none other than Toussaint Louverture (also known as Toussaint L’Ouverture).

Toussaint Louverture

Wikimedia CommonsToussaint Louverture.

Born into slavery on May 20, 1743, in Saint-Domingue, Toussaint Breda (his surname being that of the plantation where he was born) was the eldest son of Gaou Guinon, an African prince captured by slavers.

Louverture learned of Africa from his father while his godfather, a priest named Simon Baptiste, taught him to read and write. Impressed by Louverture, Breda plantation manager Bayon de Libertad allowed Louverture access to his personal library.

By the time he turned 20, the well-read and trilingual Louverture had also gained a reputation as a skilled horseman and an amateur physician. Louverture even secured his freedom from de Libertad even as he continued to manage his former owner’s household personnel and to act as his coachman.

But the August 22, 1791 “Night of Fire” — in which Saint-Domingue’s slaves revolted by setting fire to plantation houses and fields and killing whites — convinced the freed 48-year-old to join the growing insurgency. It was then that he took the name Louverture (“the one who finds an opening”).

Louverture wouldn’t get his opening right away. Two years after the “Night of Fire” — and under attack from French Royalists, the Spanish, and the British — Saint-Domingue’s Jacobin governor issued a decree abolishing slavery in an attempt to gain slave support. However, Louverture and his compatriots knew that the governor was overstepping his bounds and that the French government hadn’t yet actually abolished slavery. Thus, the slave insurgency’s leadership at first chose to align itself with Spain and against France.

Then, following the decision of the Jacobins in France to abolish slavery throughout the French territories, L’Overture switched alliances, allying with France against Spain. In May 1794, therefore, Toussaint Louverture joined the French revolutionaries and reached greater heights of power and import.

From 1794 to 1802, Toussaint Louverture rose to become the dominant leader in Saint-Domingue and proved himself to be both a political and military genius. In ten years of warfare, he formed groups of slaves into a disciplined army that astonished European commanders and defeated the best troops European governments could muster.

The Revolution Spreads To Saint-Domingue

Wikimedia CommonsThe Battle at San Domingo.

By abolishing slavery through a grassroots social revolution, the events transpiring in Saint-Domingue struck fear into the hearts of the powerful both in the region and abroad, who had invested in maintaining the status quo. The United States, for one, hastened to send arms to quell the uprising. Even George Washington wrote, “How regrettable to see such a spirit of revolt among the Negroes.”

Washington’s lamentations did not keep the slave revolt of Saint-Domingue from inspiring slaves in the United States. As the American abolitionist Frederick Douglass said:

“When they struck for freedom, they builded better than they knew. Their swords were not drawn and could not be drawn simply for themselves alone. They were linked and interlinked with their race, and striking for their freedom, they struck for the freedom of every black man in the world.”

Still, Louverture’s mark on history wouldn’t be limited to slave revolt and abolition alone. Operating under the title of General-in-Chief of the Army, Toussaint Louverture led the French in ousting the British and then in capturing the Spanish-controlled half of the island.

Back in France, meanwhile, a coup had overthrown the Jacobins and left the Directory in power. The Directory formally approved Louverture’s increasing leadership in Saint-Domingue, making him Lieutenant Governor of the colony in April 1796 and commander in chief of the French forces in 1797.

By 1801, although Saint-Domingue remained a French colony, Toussaint Louverture ruled it as an independent state. He even drafted a constitution in which he reiterated the 1794 abolition of slavery and appointed himself governor.

This freedom was short-lived, however. When Napoleon came to power, he responded to the pleas of the plantation owners by reinstating slavery in the French colonies, once again plunging Saint-Domingue into war.

Defeating Napoleon

Wikimedia CommonsThe 1803 Battle of Vertières, at which the rebels finally defeated Napoleon’s forces.

Napoleon sent 35,000 troops to Saint-Domingue in 1802.

The former slaves fought back and won their independence for a second time, soon inaugurating the Republic of Haiti. This made Haiti the first independent nation of the Caribbean, the only nation in the Western Hemisphere to have defeated three European superpowers (Britain, France, and Spain), and the only nation in the world established as a result of a successful slave revolt.

Yet before true independence would come, Louverture and Napoleon struck a deal: the latter agreed to recognize the island’s independence, and the former in turn agreed to retire from public life.

Events would soon turn for the worse for Toussaint Louverture. A few months later, the French invited him to a negotiation and promised his safety. But when he arrived, the army (under Napoleon’s orders) arrested him, putting him on a ship headed for France.

When Louverture arrived, Napoleon ordered that he be placed in a dungeon in the Alps, where he died on April 7, 1803.

Library of CongressThe death of Toussaint Louverture in 1803.

In a cruel turn of events, six months later Napoleon decided to give up his New World possessions and instead focus his efforts on his European empire. Haiti had its independence back.

This, too, came at a cost. In the years following Haitian independence, European powers did not recognize the republic and France eventually succeeded in levying a crippling tax on Haiti as the price of its independence.

Ever since, Western powers have continued to meddle in Haitian political life right up until the present, often with devastatingly negative consequences: today, the island nation is one of the poorest countries in the world, with 80 percent of residents living below the poverty line.

Only time will tell whether the spirit of Toussaint Louverture will again arise and bring Haiti once more to the forefront of the oppressed’s struggle for justice and freedom.

After learning about Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution, read up on four little-known American slave revolts that helped bring about the Civil War. Then, have a look at the most inspiring one-person protests in history.