When Alfred Watkins first put forth the idea that straight lines connect landmarks across Britain in 1921, he didn't believe that these pathways had any mystical significance — then subsequent theorists transformed ley lines into something paranormal.

In 1921, amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins made a remarkable discovery. He noticed that ancient sites around Britain all fell into a strange alignment. Both man-made and natural monuments could be connected by perfectly straight paths. He coined these routes “ley lines” — and opened up a world of supernatural and spiritual beliefs.

Wikimedia Commons The Malvern Hills in England, where Alfred Watkins first came up with his theory on ley lines.

So, what are ley lines exactly?

According to theorists, they are invisible lines that crisscross around the globe — similar to latitudinal and longitudinal lines — dotted with monuments and natural landforms. Some believe they carry rivers of supernatural energy and that there are pockets of concentrated energy at the places where they intersect that can be harnessed by certain individuals.

Of course, ley lines aren’t without their skeptics. While the idea can be tantalizing to some, others are wary of ascribing to the paranormal component of ley lines — and often attribute much of the theory to pure coincidence. So, which is it?

Alfred Watkins And His Marvelous Discovery

Alfred Watkins was born in Hereford, England, on Jan. 27, 1855, to an affluent family who operated several businesses in the small town. As Watkins grew up, he began taking on duties for the family trades and developed an intimate knowledge of the region.

Watkins also had a deep interest in photography, and he established himself as both a respected landscape photographer and a craftsman. He even developed the Watkins Bee Meter, a small exposure meter with a timing chain for traveling photographers.

F.C. Tyler/Tate MuseumAlfred Watkins, a well-respected photographer who came up with the theory of ley lines.

But Watkins is remembered today less for his photography and more for his theory of ley lines.

Per the Tate Museum, Watkins, by his own account, first discovered ley lines during a “rush of revelations” on June 30, 1921.

He was standing on a hill in Blackwardine when he saw on a map that a number of ancient sites stood in a perfectly straight line. His view from the top of the hill seemed to confirm this, and he followed his initial observation by examining the view from other tall hills in the area.

Watkins said he was “unhampered by other theories” and that his observations were “yielding astounding results in all districts.” He further theorized that starting at any one point along the line and traveling along it would also reveal sites not marked on maps, such as forest glades, trenches, or notches on crested hills.

Watkins’ view of the world echoed other “alignment” theories, all of which largely suggested the same thing — that ancient humans were in tune with some ethereal force, largely unobserved by modern man, and constructed their sacred places in specific spots where that force was strongest.

Watkins’ theory didn’t win over everyone, however, and to this day, the existence of ley lines is a heavily debated topic.

How The Mythology Of Ley Lines Evolved Over Time

Watkins claimed that ley lines are straight alignments connecting various historic structures, landmarks, prehistoric sites, and sacred places. However, he didn’t personally attribute any mystical properties to the pathways.

He first explored his theory in detail in his book The Old Straight Track, in which he argued that ley lines represented ancient trading routes used by England’s prehistoric societies. The straight lines allowed them to travel from one place to another as quickly as possible, he posited.

British archaeologists largely disregarded Watkins’ hypothesis, though, stating that it would have been impractical for prehistoric societies to travel in perfectly straight lines for trading — just as it is today. For instance, it can be much quicker to walk around a steep hill than to climb over it.

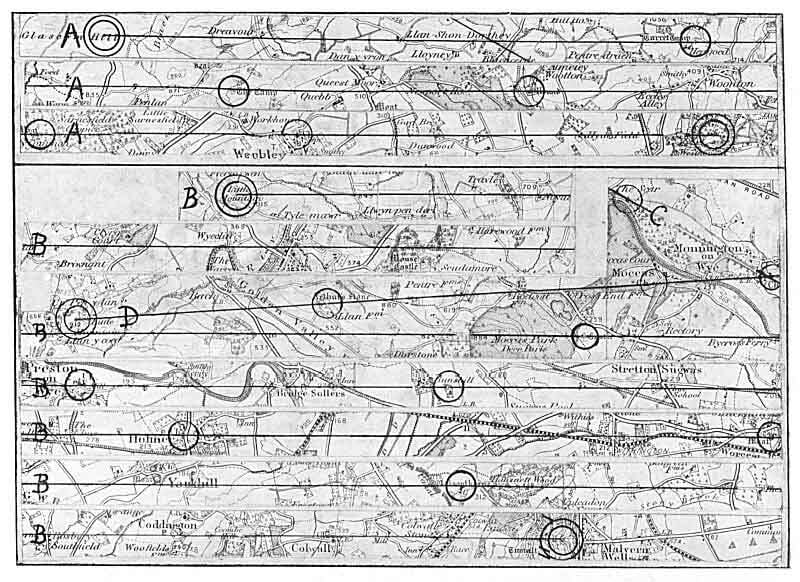

Wikimedia CommonsAlfred Watkins’ map of ley lines.

However, like many other fringe ideas, Watkins’ theory was just the foundation. Decades later, in the 1960s, Watkins’ idea saw something of a revival thanks to a man named Tony Wedd. In 1961, Wedd suggested ley lines were used by prehistoric humans to communicate with aliens. In fact, he believed they were paths created to guide UFOs visiting Earth. And in 1969, John Michell wrote about ley lines in his book The View Over Atlantis, in which he introduced the concept of “Earth energies.”

Ley lines began to take on a more esoteric, spiritual connotation around this time. No longer were they simply the trails left by ancient humans; now, they were invisible “energy lines” that only a select few could actually detect.

In January 2023, BBC interviewed artist and performer bone tan jones, a believer in these energy lines who walked from London to Stonehenge along one of these purported ley lines.

“I’ve been interested in ley lines for years,” tan jones said. “I grew up in the countryside, connected to Earth energy, so it makes complete sense to me that there are energy lines moving through the Earth.”

But the specifics of how ley lines evolved from the trade routes of ancient humans to something more mystical are rather odd.

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, ley lines became attached to numerous counterculture movements, with David Newnham writing for The Guardian in 2000: “[L]ey-line theory was to mutate and bifurcate, to bend with every passing fad, so that it frequently seemed as though its only purpose was to highlight the failings of our own times. And with each twist and turn, it became ever more firmly enmeshed in a thicket of mysticism, neo-paganism and plain superstition.”

Watkins had considered his hypothesis to be scientific in nature, though he could never definitively prove the concept to be true. Incorporating supernatural elements into the theory certainly didn’t help.

But in the 1980s, scholars Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy tried to approach ley lines with a scientific mindset — and ultimately, their findings highlighted a crucial error with the theory.

Other Explanations For Ley Lines

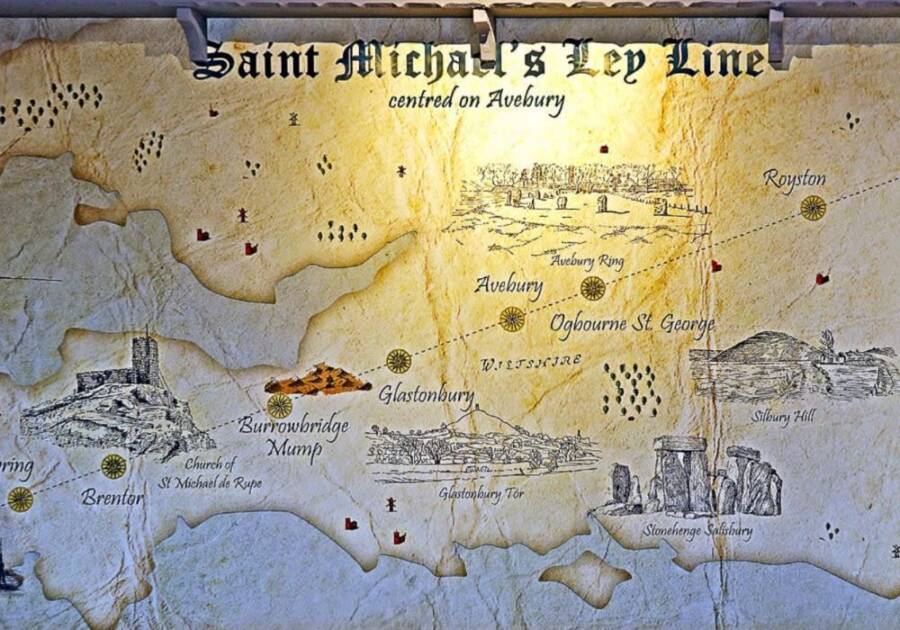

X/@RedLionAveburyA map showing St. Michael’s Line, which connects dozens of landmarks dedicated to the Archangel Michael over a 350-mile stretch between Cornwall and Norfolk.

Williamson and Bellamy’s findings did not outright disprove the existence of ley lines, but they did cast a fair amount of reasonable doubt. Essentially, by examining the locations of various archaeological sites across England, they discovered that there was such a high density of landmarks that it was essentially possible to draw a straight line in any direction and connect multiple locations. That is, anyone could create a map of ley lines.

Researcher Tom Brooks argued that keen mathematicians lived in Britain as far back as 5,000 years ago — before the Greeks had even invented geometry. He, like Watkins, examined ancient sites — 1,500 to be precise — and found that they had all been built on a series of isosceles triangles, each one guiding ancient humans to the next.

In theory, Brooks’ findings would support the existence of ley lines.

But to highlight how skewed this data was, Matt Parker of the University of London’s School of Mathematics at Queen Mary cheekily applied Brooks’ techniques of drawing ley lines maps to Woolworths stores.

“We know so little about the ancient Woolworths stores,” he jokingly told The Guardian in 2010, “but we do still know their locations. I thought that if we analysed the sites we could learn more about what life was like in 2008 and how these people went about buying cheap kitchen accessories and discount CDs.”

Evidently, three Woolworths stores around Birmingham formed an exact equilateral triangle. It was a remarkable discovery, one that fit his hypothesis, he said, by “skipping over the vast majority, and only choosing a few that happen to line up.”

Parker’s tongue-in-cheek experiment effectively reached the same conclusion as Williamson and Bellamy’s research: by choosing a limited set of data from a larger pool, it can be used to support just about any argument.

Is that to say that ley lines definitively don’t exist? No. But it does highlight how data can be skewed to push a certain idea while ignoring points that don’t fit the mold.

Basically, anyone can create a ley lines map by drawing a straight line through several ancient sites and claiming they were built on the route intentionally, just as they could form a triangle out of three Woolworths stores and say it was the result of something mystical.

After learning about ley lines, check out these ancient maps that show how our ancestors saw the world. Then, look through these stunning photos of some other invisible lines — the borders of the world’s countries.