Based on similar medieval texts, at least part of the Voynich manuscript could be about "women's secrets."

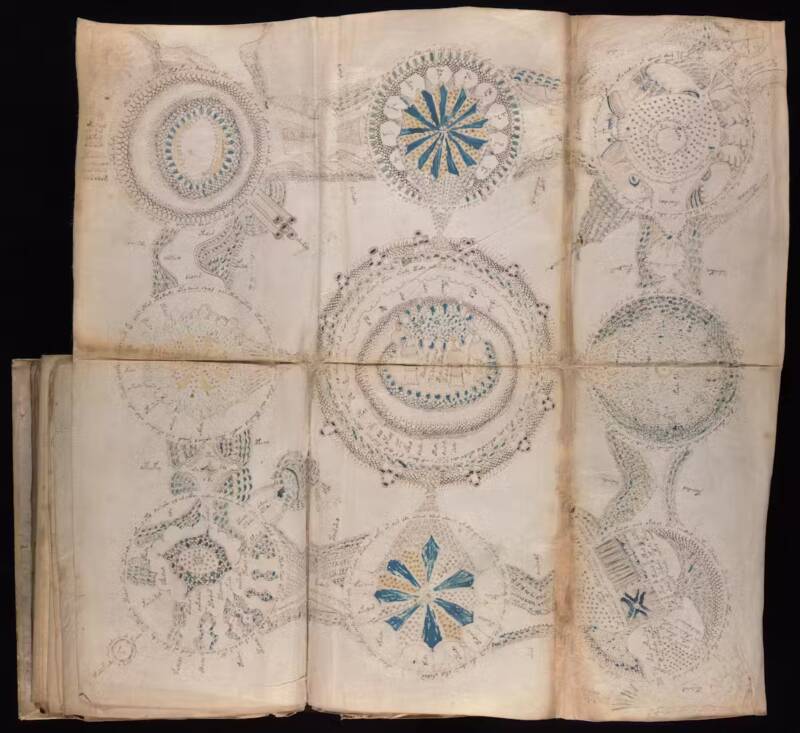

Yale University LibraryThe Rosettes, the largest illustration in the Voynich manuscript, could be representative of a medieval understanding of female sexual anatomy.

The Voynich manuscript, a centuries-old text written in an unknown language and featuring odd, otherworldly illustrations, has long fascinated historians.

Since its rediscovery in 1912, countless scholars have attempted — and largely failed — to decipher this strange book’s meaning and origin.

The late-medieval text is rife with illustrations depicting a wide range of objects, from stars and planets to plants and naked women.

This odd hodgepodge of imagery, coupled with the indecipherable text, has only muddied the mystery of the book’s meaning further. But now, a duo of researchers believe they have uncovered some of the manuscript’s meaning.

Sex Could Be One Of The Subjects Detailed In The Voynich Manuscript

In a recent study published in the journal Social History of Medicine, authors Keagan Brewer and Michelle L. Lewis examined the Voynich manuscript’s most prominent illustration, the Rosettes, and compared it to other texts from the medieval period.

Even from a glance, it’s clear that the Voynich manuscript touches on a number of topics, including botany, astrology, astronomy, and anatomy, based purely on the various illustrations within the document. However, the meaning of these images has often appeared contradictory.

“One section contains illustrations of naked women holding objects adjacent to, or oriented towards, their genitalia,” Brewer writes in The Conversation. “These wouldn’t belong in a solely herbal or astronomical manuscript. To make sense of these images, we investigated the culture of late-medieval gynecology and sexology — which physicians at the time often referred to as ‘women’s secrets.'”

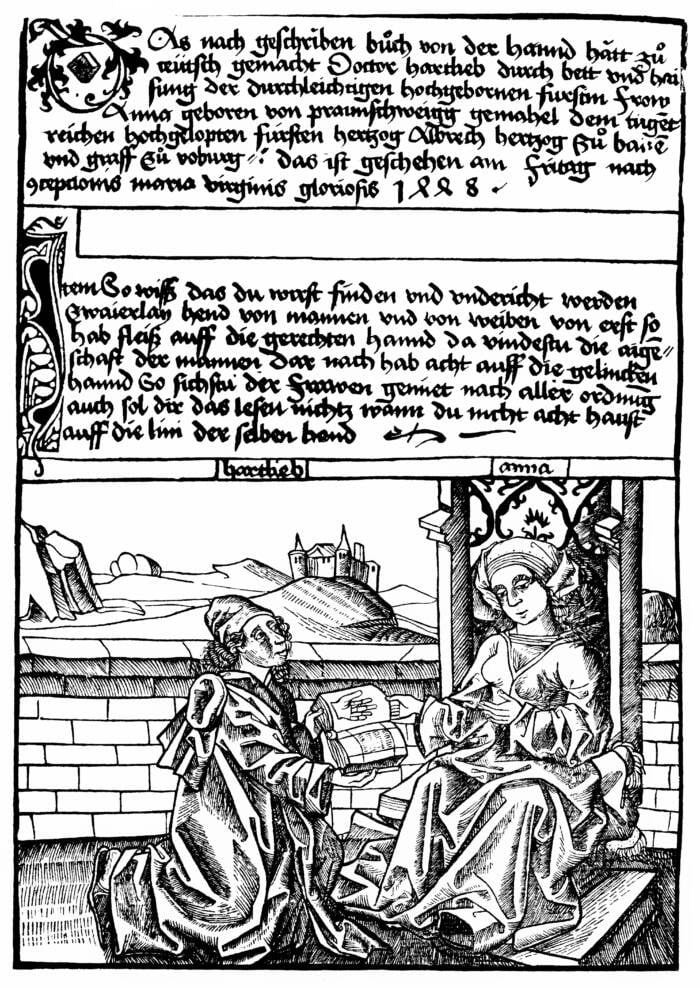

First, Brewer and Lewis turned to the writings of Bavarian physician Johannes Hartlieb, who lived from 1410-1468 — around the time and place the Voynich manuscript was created.

history_docu_photo / Alamy Stock PhotoA portion of one of Johannes Hartlieb’s texts.

Hartlieb often wrote about many of the topics covered in the Voynich manuscript, including plants, astronomy, women, and magic. However, Hartlieb was very much a man of his time — rather conservative in his views on women’s sexuality, and fearful that God would punish him for writing about “women’s secrets” so brazenly.

As such, Hartlieb often suggested employing “secret letters” like ciphers or secret alphabets to censor medical information that could lead to contraception, abortion, or sterility.

Brewer writes that “analyzing [Hartlieb’s] work has helped us understand the attitudes that would have inspired the use of encipherment at the time.” According to Brewer, Hartlieb was greatly concerned that should “women’s secrets” become widely known, it could result in an increase in extramarital sex, and that God would punish him for sharing this forbidden knowledge.

In his various other writings, Hartlieb “refuses or hesitates” to write about topics like postpartum vaginal ointments, women’s sexual pleasure, and contraceptive or abortive plants.

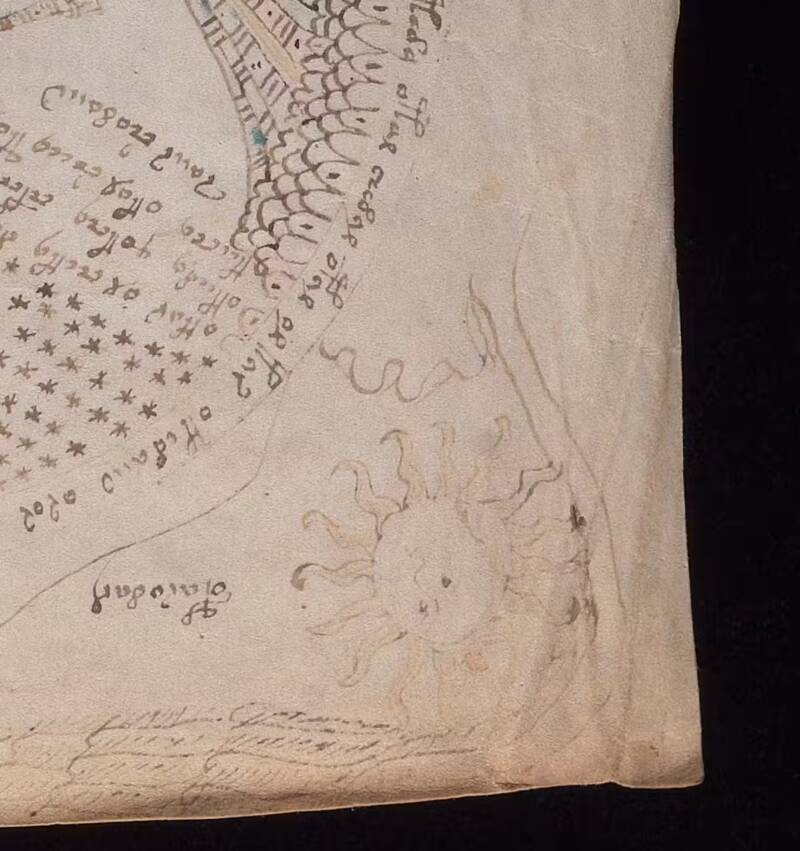

Yale University LibraryA sun in the corner of the Rosettes, which could relate back to Aristotle’s belief that the sun warmed the embryo during pregnancy.

Hartlieb firmly believed that this knowledge was for noble men only, and that it should be kept away from women, sex workers, common folk, and children.

That’s not to say that the authors are insinuating that Hartlieb was the Voynich manuscript’s author. Rather, by looking at Hartlieb’s inclinations in his own work, we can gain an understanding of the larger sensibilities of the time during which the Voynich manuscript was written.

“We don’t believe he authored the Voynich manuscript,” Brewer clarifies to All That’s Interesting via email. “No enciphered writing known to be written by him is extant. Why we looked closely at him is because he suggested to his two lords (Siegmund and Friedrich) that they should use encipherment to hide women’s secrets… We take him as a case study through which to speculate about the Voynich authors’ motivations.”

And Hartlieb was hardly the only scholar doing this self-censorship. Sometimes this censorship simply involved obscuring a genital term or plant name in a recipe. In the case of one Bavarian text containing recipes for invisibility and magical spells designed to sexually coerce women, it involved removing entire pages from the manuscript.

“We see the Voynich manuscript as inspired by the same broadly-held censorial impulses present among late-medieval medical writers and readers when it comes to sexual topics,” Brewer tells All That’s Interesting. “Which had a degree of crossover with magic.”

This offers at least one major explanation for the indecipherable text of the document. But what other clues does the Voynich manuscript itself provide to support this theory?

How The Voynich Manuscript’s Largest Illustration Could Hint At Its Subject Matter

The Rosettes is the Voynich manuscript’s “largest and most elaborate illustration,” a sprawling, multipage foldout of nine connected circles, astronomical symbols, tubes, bulbs, passageways, castles, and city walls.

At first glance, it looks something like a city map, though not like any city that has ever existed on Earth. However, based on the patriarchal standards seen in other late-medieval works, the Rosettes could hint at a deeper meaning.

“In late-medieval times the uterus was believed to have seven chambers, and the vagina two openings (one external and one internal),” Brewer writes. “We believe the nine large circles of the Rosettes represents these, with the central circle representing the outer opening, and the top-left circle representing the inner opening.”

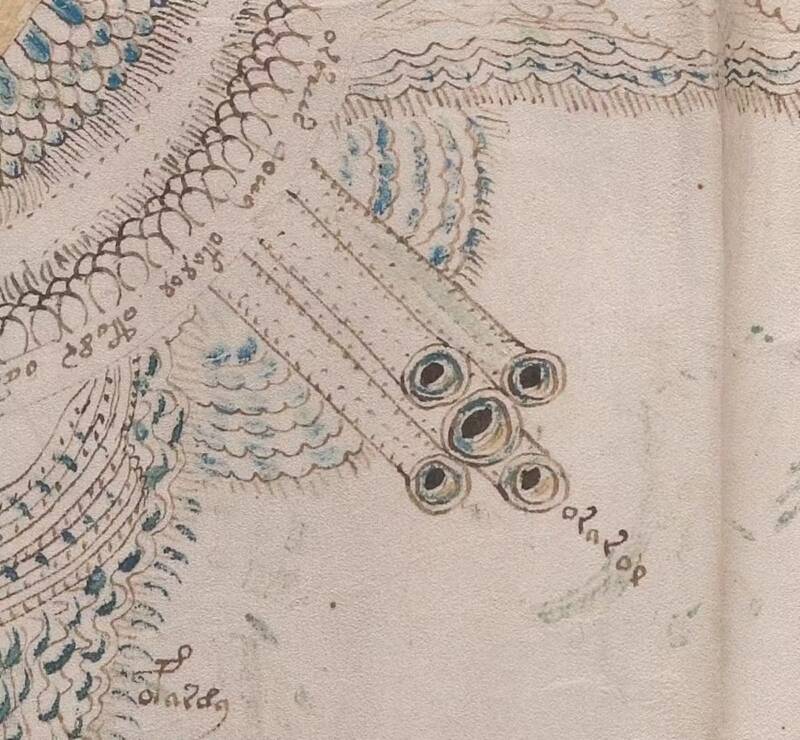

There are other subtle clues throughout the illustration that could relate back to the late-medieval understanding of sex as well. Near the top-left circle, for example, are five small tubes running toward the illustration’s center. Based on the writings of the influential Persian physician Abu Bakr Al-Rāzī, these could represent the five small veins that were believed at the time to be present in the vaginas of virgins.

Yale University LibraryThe “five veins” of the Rosettes.

Late-medieval physicians also believed that both men and women produced “sperm” for contraception, though they acknowledged that these were separate male and female components. Throughout the Rosettes, these “sperm” could be represented by blue and yellow colors.

It was also believed that women received pleasure from the motion of these two “sperms” within the uterus, possibly depicted through the patterns in the Rosettes.

Yale University LibraryThe castle at the center of the Rosettes, which might represent female genitalia.

Even the imagery of the castles could relate back to women’s sexual anatomy. The German term schloss had multiple meanings, including “castle,” “lock,” “female genitalia,” and “female pelvis.”

Brewer acknowledges that many of these images are open to interpretation, noting that “our proposal is worth close scrutiny.”

That said, the proposal does seem to fit in with the overall culture of the time, and as Brewer says, it “resolves many of the manuscript’s apparent contradictions.”

It’s only a small portion of the Voynich manuscript, but if Brewer and Lewis’ findings are even remotely accurate, it could pave the way for other scholars to further decode this mysterious medieval manuscript.

After learning about one possible meaning behind the Voynich manuscript, learn all about the Codex Gigas, a.k.a. the Devil’s Bible. Or, dive into the mystery of who really wrote the Bible.