From 1765 to 1996, Ireland’s laundry institutions claimed to help vulnerable women and girls. Instead, they forced them into prison-like conditions.

Unknown/Wikimedia CommonsYoung girls and even infants were sent to Ireland’s Magdalene asylums.

In 1993, a Dublin convent sold a parcel of land. But when the developers began digging, they uncovered a decades-old scandal.

Under the Irish soil lay a mass grave that, according to Irish Central, contained 155 bodies. Most had no death certificate. An investigation revealed that the grave interred women who’d been sent to the Magdalene laundries.

These “asylums,” meant to reform women, instead abused them. Over the course of more than 230 years, girls living in the laundries were forced to work for no pay and to live in terrible conditions with no schooling.

Unknown/Wikimedia CommonsAn early 20th-century photograph of women doing laundry in a Magdalene asylum.

When the scandal broke, survivors of the asylums came forward to condemn the practice.

“You didn’t know when the next beating was going to come,” survivor Mary Smith later said in an oral history conducted by Irish Research Council.

Like many survivors, Smith was not a criminal. She was sent to a Magdalene laundry in Cork after being raped.

The History of the Magdalene Laundries in Ireland

The Magdalene laundry system dated back to the mid-18th century. Ireland’s first asylum opened in Dublin in 1765 with the intent to prevent prostitution. The asylum sheltered unwed mothers and women who had premarital sex, hoping to prevent their slide into sex work. Some parents sent their daughters to these asylums to hide out-of-wedlock pregnancies.

During this earlier period, women stayed in the asylums for a short time. They learned a skilled trade to support themselves after their release. And many entered the asylums by choice.

Wikimedia CommonsIn County Cork, the Religious Sisters of Charity ran a laundry.

But the Magdalene asylums eventually became long-term prisons for women rejected by society. By the time the Republic of Ireland declared independence in 1922, the laundries had become a for-profit system run by four religious groups: the Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of Charity, the Good Shepherd Sisters, and the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity.

The Girls of the Magdalene Laundries

Ireland’s Magdalene laundries promised to reform “fallen” women. But who was sent to the asylums?

The nuns who ran the asylums took in “promiscuous” women. That category included unwed mothers – and their children. The people incarcerated in the convents also included victims of sexual abuse, women who were deemed too flirtatious, women with disabilities, orphans, and impoverished children.

While the Magdalene laundries were almost entirely run by Catholic nuns, the Irish government helped pay for them in exchange for laundry services. And the government also sent women to the asylums, including patients in mental hospitals and wards of the state.

In the laundry system, Catholic nuns vowed to reform their charges through harsh methods.

Suffering was penance for sin, the nuns of the Magdalene laundries preached. So the girls were forced to work long hours for no pay.

Local businesses, public hospitals, and government agencies dropped off their laundry at the convents. The girls washed and ironed the clothes. If they refused to work, the nuns withheld food or physically abused the girls.

“Redemption might sometimes involve a variety of coercive measures,” historian Helen J. Self writes of the laundries in Prostitution, Women and Misuse of the Law: The Fallen Daughters of Eve, “including shaven heads, institutional uniforms, bread and water diets, restricted visiting, supervised correspondence, solitary confinement and even flogging.”

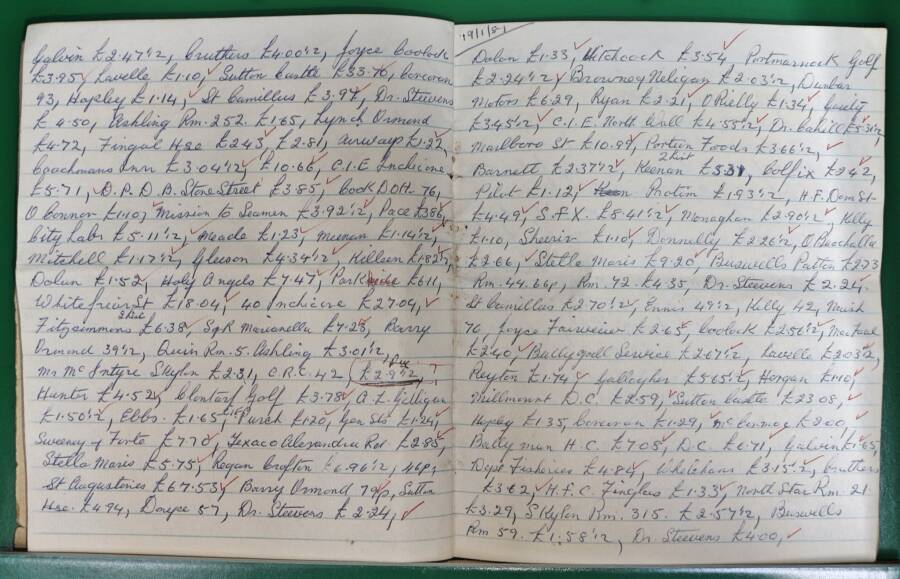

The Little Museum of DublinA ledger listing the girls and women at a Magdalene laundry in Dublin.

“Survivors speak of constantly being under surveillance, being verbally insulted, feeling cold, having a poor diet and enduring humiliating and inadequate hygiene conditions,” declares the advocacy organization Justice for Magdalenes. “None of the girls received an education.”

Babies born in the asylums were often taken from their mothers and given to other families. But in some homes, babies faced a much worse fate. At the St. Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, the remains of close to 800 babies were found in a septic tank in 1975.

As reported by RTÉ, an investigation into the home suggested that poor treatment of illegitmate children born there had “signifantly reduced” their chances of survival.

The Tragic Life Of Mary Smith

Mary Smith was sent to a Magdalene laundry in Cork after she was raped. The nuns explained to Smith that she had to be locked away “in case [she] got pregnant.”

At the laundry, the nuns cut Smith’s hair and gave her a new name. Like the other inmates, Smith had to work in the laundry and follow a vow of silence. The nuns also beat her.

The horrific conditions further traumatized Smith, who was only around 16 years old when she was locked away. She later said the nuns made the girls feel like they weren’t human.

“We were worse than humans,” she said. “We used to have to line up… and they used to make us hold our hands and the nuns used to say to us, ‘say after me: I am a nobody. I am a nobody’ – they used to keep telling us to say that, ‘I am a nobody.'”

Years later, Smith could not even remember how long she spent at the asylum. Smith later learned that she’d been born at a different Magdalene laundry to an unwed mother sent to the asylum by her priest. Tragically, Smith’s mother died before they could be reunited.

Survivors Speak Out

Elizabeth Coppin grew up in the Magdalene laundry system. When Coppin was two years old, her stepfather beat her, so the government removed Coppin from her home and sent her to an asylum.

Per court order, she was to be a ward of the court until she reached the age of 16. Instead, she was confined in the laundry system until 19.

While there, the nuns starved her, beat her until she was welted, locked her in cupboards, and forced to wear soiled clothes on her head if she wet herself. At the age of 12 or 13, Coppin set her clothes on fire in a suicide attempt. When she survived, she was not given any medical treatment.

“It dawned on me that I would be there for life, that I’d be buried in a mass grave; there were whispers that went around,” she told the New York Times. “I saw the people who were there, who were broken, institutionalized, illiterate, from living in a dark, dark place with no way out. I remember asking myself the questions, ‘What will I do? How will I get out?'”

When she was 17, Coppin managed to escape the laundry. Three months later, child protection workers forced her to return.

Julien Behal/PA Images via Getty ImagesSurvivors Mary Smith, Marina Gambold, and Diane Croghan (left to right) attend a 2013 press conference on the Magdalene Commission Report.

Marina Gambold also survived the Magdalene laundries.

“I was working in the laundry from eight in the morning until about six in the evening,” Gambold told the BBC. “I was starving with the hunger, I was given bread and dripping for my breakfast.”

When she accidentally broke a cup, the nuns tied a string around Gambold’s neck and made her eat off the floor.

“It was common for the girls and women to believe that they would die inside,” reports Justice for Magdalenes. “Many did.”

The Abuse Scandal Breaks

Shockingly, the Magdalene laundries operated well into the 1990s – and the last one closed in 1996.

It’s estimated that up to 300,000 “fallen” women passed through Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries between 1765 and 1996. Records show that at least 10,000 girls and women were sent to the laundries between 1922 and 1996. But the true number is likely much higher, as many laundries kept inaccurate records and neglected to report when girls died.

After the scandal broke, the United Nations investigated the Magdalene laundries for violating human rights. The UN concluded that the victims were “deprived of their identity, of education and often of food and essential medicines and were imposed with an obligation of silence and prohibited from having any contact with the outside world.”

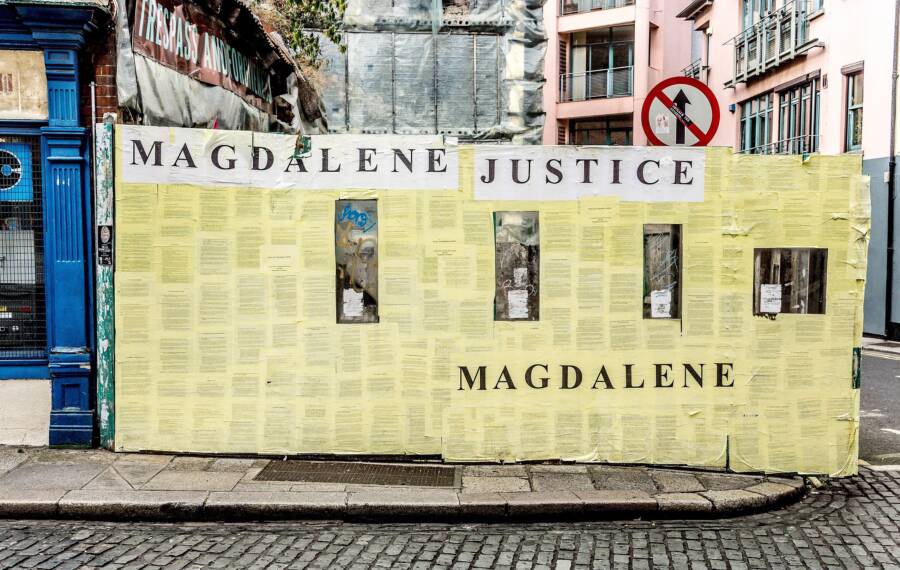

William Murphy/Wikimedia CommonsProtest art from 2012 demands justice for the women of the Magdalene laundries.

Magdalene Laundry Survivors Grapple With Their Pasts

Survivors of the abusive laundry system often fled Ireland. “A lot of them didn’t even have passports,” journalist Norah Casey said. “They got the hell out of Ireland as soon as they could and never came back.”

In 2018, a group of 220 survivors met in Dublin. While within the asylums many girls were isolated, many survivors were able to connect with each other in the aftermath to share their stories.

“I heard about one woman who is here somewhere today who I think I knew in Kerry,” said Elizabeth Coppin. “I’ll be looking for her later.”

While the Magdalene laundries have been closed for decades, many women still live with the scars of their abuse.

After investigations into the laundries revealed that about a quarter of women in them were sent there by the Irish state, Ireland set up a compensation scheme to pay surivors reparations. Per Reuters, the Irish government agreed to pay up to 58 million euros, or about $75 million, to hundreds of laundry survivors.

“This has destroyed my life to date,” Smith said after the compensation scheme was announced. “All this that is going on will never take away our hurt.”

Ireland’s laundry system was not the only case where vulnerable children suffered abuse. Next, go inside the Elan school for troubled teens, and then read about the Indigenous residential schools system.