When Malice Green — an unarmed Black man — was beaten to death by the police on November 5, 1992, many wondered if justice was even possible.

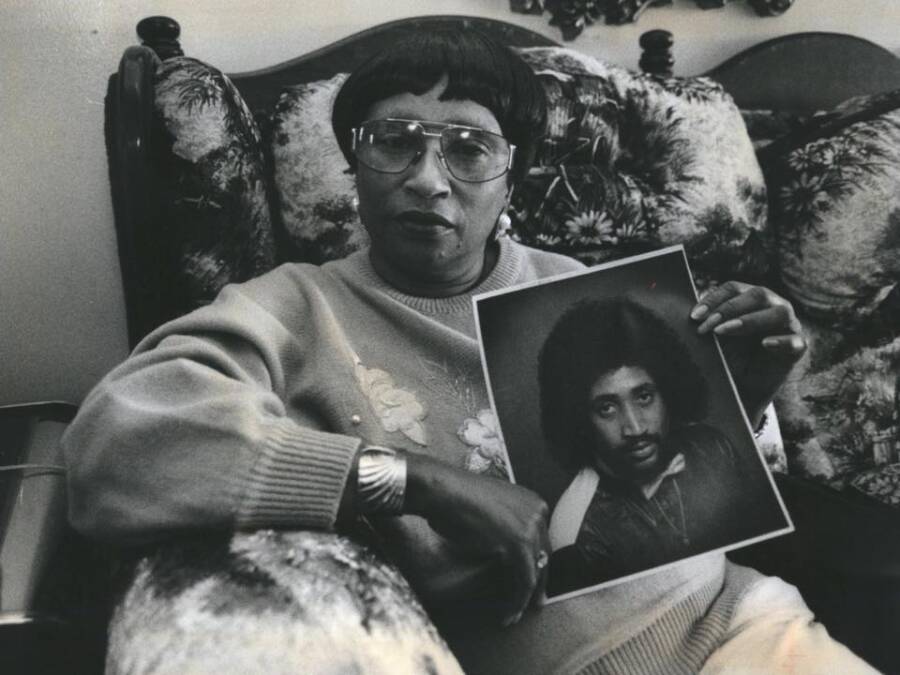

FacebookMalice Green’s grieving mother.

Malice Green was 35 years old when police in Detroit beat him to death. The unemployed steelworker had just driven his friend home when plainclothes officers approached and demanded to see his license. As he reached for the glovebox, they used their metal flashlights as weapons — and bashed his skull in.

It had only been a year since the 1991 Rodney King beating in Los Angeles, which was captured on film and led to extreme racial tensions. These escalated to city-wide riots when three of the four police officers involved were acquitted of assault in 1992. After Green’s death on Nov. 5, 1992, a similar trial awaited.

News of white police bludgeoning an unarmed Black man to death spread across Detroit like wildfire. Malice had merely been parked in a part of town with purportedly heavy drug activity when officers Larry Nevers and Walter Budzyn killed him. They claimed physical force was necessary — because he refused to drop an item in his hand.

Their response was a grotesque beating that didn’t end when other officers arrived at the scene, or Green’s lifeless body fell out of the car. He was eventually taken to Detroit Receiving Hospital but had already died. He immediately became a symbol of police brutality, and an entire city awaited justice.

Police Attack Malice Green On No Evidence

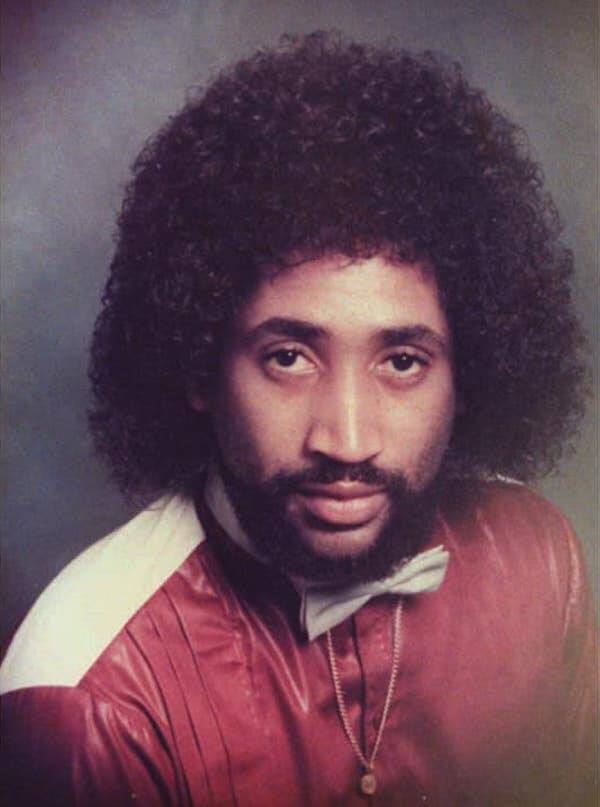

Born on April 29, 1957, in Wilmot, Arkansas, Malice Green and his family moved to Detroit, Michigan, when he was 12 years old. He was a solid student and graduated from Western High School in 1975. Finding work at the Morton Manufacturing Company in Illinois, he lived in Waukegan and Chicago as a new adult.

FacebookMalice Green died at 35.

He moved back to Detroit to stay with his mother in March 1992, with friends saying he did so to reunite with his estranged wife — and be closer to his two daughters from prior relationships.

Though newly unemployed, Green was known for his generosity. He tried hard to find work, tended after his sister’s children, and barbecued on the porch for anyone who passed by. It was completely in character Malice Green drive friend Ralph Fletcher across town on Nov. 5, 1992.

Green took him to a party store and dropped him back off at home. Unbeknownst to him, Officers Nevers and Budzyn had been tailing Green in an unmarked car. It was around 10:30 p.m. when they blocked his exit at Fletcher’s residence — a suspected crack house — and exited their vehicle to ask for his license.

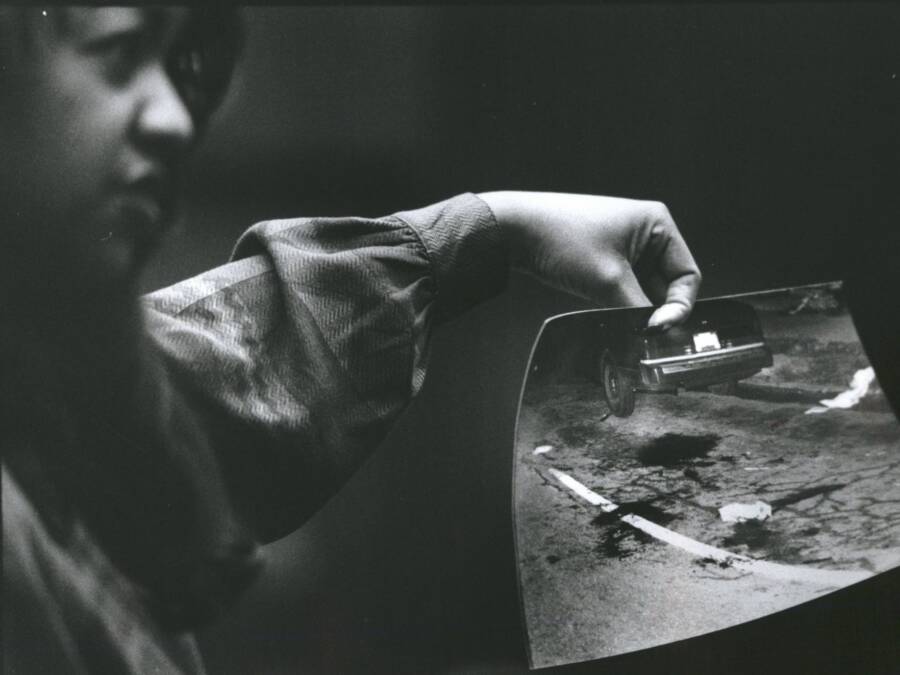

FacebookA photograph of the murder scene.

Green reached for the glove box as instructed, but was holding something in his fist. Police suspected crack cocaine, and began beating Green when he failed to drop it. They struck him on the hand, ribs, and head, resulting in a seizure. Five uniformed officers, among them Robert Lessnau, arrived to cuff him.

EMTs watched officers beat Green’s prone body before taking him to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival at 11 p.m. Budzyn later claimed he found four crack rocks in Green’s car and a knife on his person.

Detroit Police Go On Trial For The Murder Of Malice Green

Within 24 hours, Police Chief Stanley Knox suspended four of the officers involved. Detroit’s first Black mayor, Coleman A. Young, said firmly that police had “murdered” Green. While Nevers and Budzyn were charged with second-degree murder and Officer Robert Lessnau was charged with assault with intent to do bodily harm, the defense had already found an angle.

FacebookMalice Green’s bludgeoned body.

Green’s arrest record included drunk driving on July 3, 1989, and trying to flee a squad car by kicking its door. He was accused of hitting his wife later that year and convicted in May 1990 of pushing two officers who answered yet another domestic abuse call.

Furthermore, Malice Green’s autopsy yielded .50 micrograms of cocaine per milliliter of blood in his system. It was this history of drug use and violent behavior that the defense would wield in court.

The trial against Nevers, Budzyn, and Lessnau began in June 1993. Each defendant was granted their own jury, all predominantly Black. Most damaging to the defense was an EMT’s message to his superior on the night in question:

“What should I do if I witness police brutality/murder?” it said.

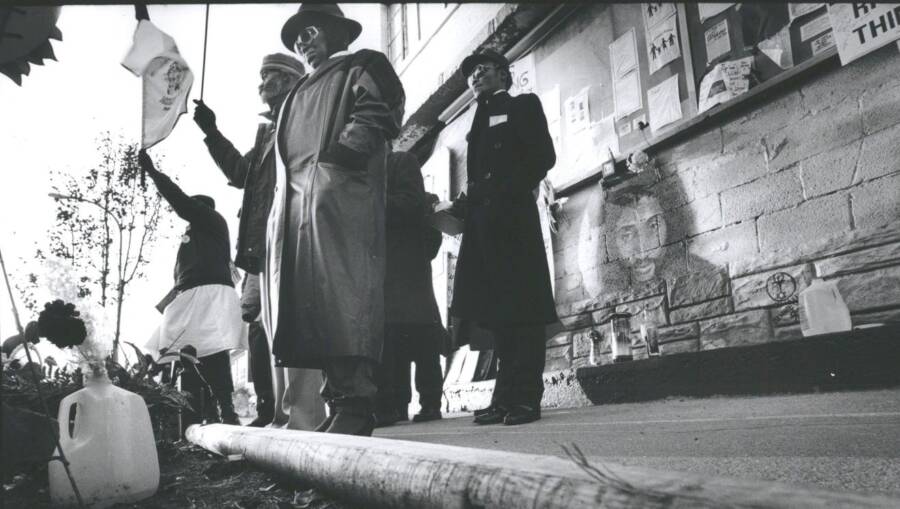

FacebookDemonstrators demanding justice in 1992.

The trial featured medical professionals debating whether Green’s cocaine use had any relevance, and it was all broadcast live on Court TV. With EMTs recalling police kicking Green’s lifeless head, and the doctor who performed the autopsy finding that such blows killed Green, the drug use defense failed.

“Our evidence was fairly compelling,” said Assistant Wayne County Prosecutor Douglas Baker. “Our evidence was showing the officer continually striking this person who’s not resisting and not fighting back. And it’s seen by a variety of people … there was a lot of agreement on what they saw.”

On Aug. 23, 1993, jurors found Budzyn and Nevers guilty of second-degree murder. Lessnau was acquitted of assault. In October, Nevers was sentenced to 12 to 25 years, while Budzyn received an eight-to-18-year sentence. The City of Detroit also settled with the Green family for $5.25 million.

The Legacy Of Malice Green And Police Brutality

Budzyn was granted a new trial on July 31, 1997, when the Michigan Supreme Court discovered that a political appointee of Mayor Young had found his way onto the jury. He had shown Spike Lee’s Malcolm X to jurors before deliberation, which some believed tainted Budzyn’s verdict.

While Budzyn was immediately released, a retrial in April 1998 saw him found guilty of involuntary manslaughter. The Michigan Court of Appeals reinstated a four-year sentence in January 1999, with Nevers using the same juror-centric appeal a successful overturning of his conviction in 1999.

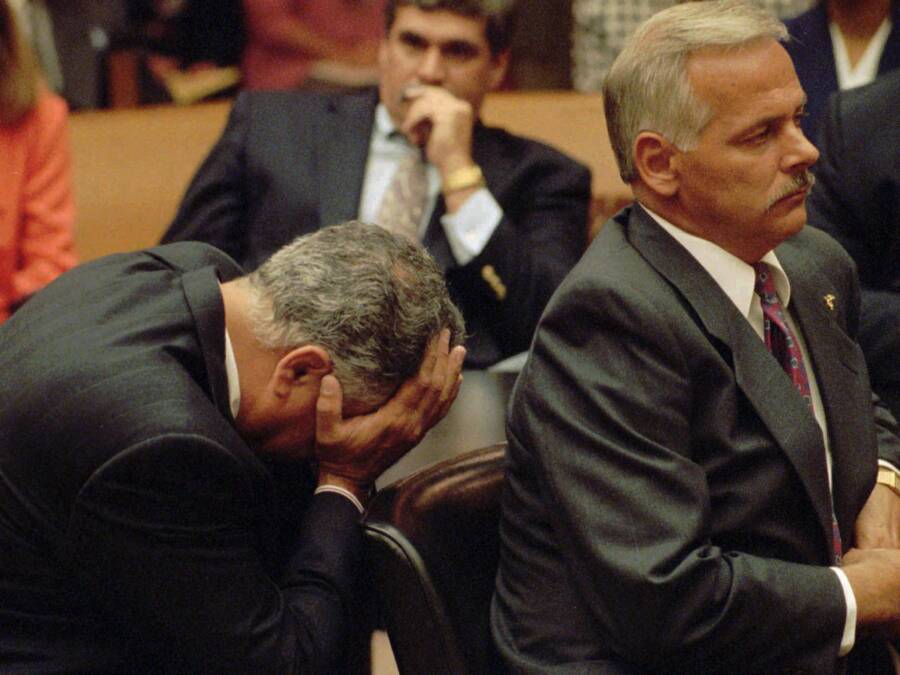

FacebookLarry Nevers (left) and Walter Budzyn (right) at sentencing.

He, too, however, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter after being released, when the U.S. Supreme Court appealed the 1999 decision in May 2000. Ultimately, Nevers released in 2001 to finish his term under house arrest — after being diagnosed with lung cancer.

Before his death on February 3, 2013, Nevers published Good Cops, Bad Verdict. The 2007 book offers his subjective account of what allegedly happened on the night in question. His claims that Malice Green’s death was not the result of police brutality are contested to this day.

After learning about Malice Green, read about the 1985 MOVE bombing. Then, learn about William O’Neal — the Black Panther who betrayed Fred Hampton.