In MI6’s early days, British naval officer Mansfield Smith-Cumming ran a spy agency full of daring eccentrics who used swords disguised as canes, poison-tipped rings, and invisible ink made from their own bodily fluids.

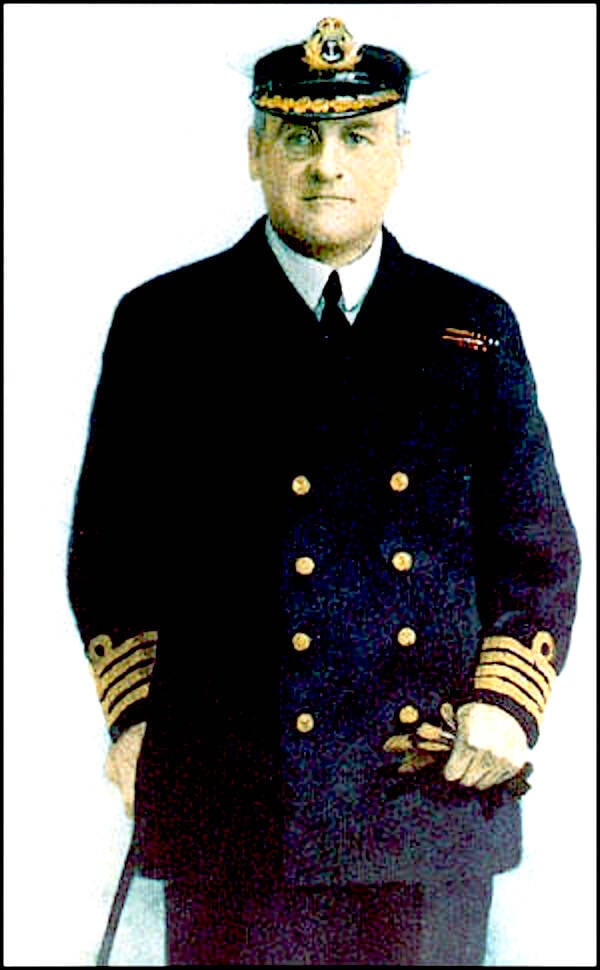

Wikimedia CommonsCaptain Sir Mansfield George Smith-Cumming helped develop Britain’s spy agency, MI6.

He wore a golden monocle and had a wooden leg. His loopy, green ink signature — simply the letter C — helped inspire the James Bond character “M”. His name was Captain Sir Mansfield George Smith-Cumming, and he was a spy.

And not just any spy. From 1909 until his death in 1923, Smith-Cumming helped develop the nascent MI6, Britain’s foreign intelligence service, by which James Bond was famously employed.

Appropriately, much of Mansfield Smith-Cumming’s life is shrouded in secrecy. But some facts are known. And the legends surrounding his time as the head of MI6 endure to this day.

Birth As A Spymaster

Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty ImagesMansfield Smith-Cumming, right, in 1907. Appropriately, the spymaster is facing away from the camera.

Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming was born simply Mansfield George Smith, on April 1, 1859. Little is known about his childhood — except that it was quite short. By the time he was 12, he’d joined the Royal Navy.

In the Navy, Smith-Cumming had a chance to see the world. He patrolled the East Indies, fought Malay pirates, and was decorated for his actions in Egypt. Smith-Cumming climbed the ranks and became a Flag Lieutenant in 1885.

His naval record describes a “clever” officer with a knowledge of electricity and photography, who could also speak French and draw rather well.

Unfortunately, Smith-Cumming lacked the one attribute needed to be an effective sailor — sea legs. He suffered from severe sea sicknesses and was forced to retire from the Royal Navy in 1885.

Back on solid land, Smith-Cumming married Leslie Marian Valiant-Cumming in 1889. He stuck her last name to the end of his own, thus shifting identities — and acquiring the “C” that would later cement his legacy as a spymaster.

The facts around Smith-Cumming’s entry into the world of spycraft are — unsurprisingly — opaque. But a few things are known.

In 1909, Smith-Cumming received a mysterious letter inviting him to come to London. The letter — which may have come from Arthur Wilson, formerly one of his naval commanders — promised him “something good.”

That “something good” was the Secret Service Bureau, which had been established in 1909. Smith-Cumming was tasked with expanding the foreign aspect of the SSB, called, among other things, the Foreign Intelligence Service. Why set up a spy agency? At the time, the British were paranoid about German spies in their midst.

“Refuse to be served by a German waiter,” the Daily Mail suggested. “If your waiter says he is Swiss, ask to see his passport.”

British officials, too, were concerned about “an extensive system of German espionage” run by German nationals living in Britain.

Thus, they decided to fight fire with fire — and set up an espionage agency of their own.

Mansfield Smith-Cumming Helps Build A Spy Agency

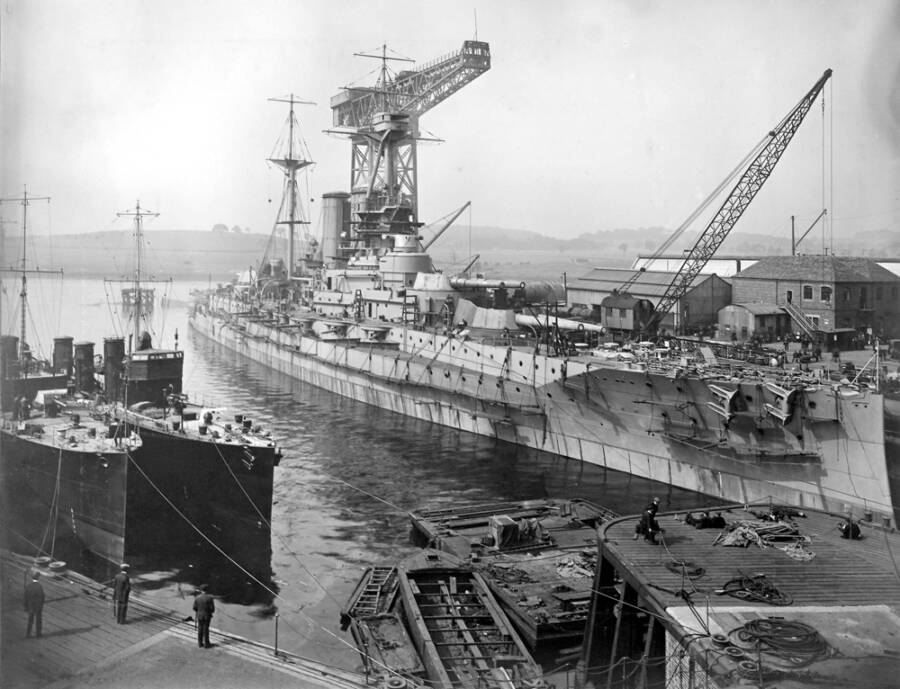

Wikimedia Commons/Imperial War MuseumA Germany military build up in the early 20th-century made British officials nervous.

At first, Mansfield Smith-Cumming didn’t have much to do. After his first day at work in October 1909, he wrote in his diary: “Went to the office and remained all day, but saw no one, nor was there anything to do there.”

Smith-Cumming found himself working from the ground up in a country that had felt no need for spies since the time of Napoleon. Britain’s Foreign Office had maintained an espionage fund for decades, and spies had been informally engaged as early as the reign of Elizabeth I.

But nothing like a formal agency had ever been seriously considered until the vague threat of a German incursion crept in British minds.

The Secret Service Bureau was under the command of Major Vernon Kell, Smith-Cumming’s superior, and had a minuscule budget, no guidelines, and no agents.

What’s more, the Army considered the SSB to be its sole property, and Smith-Cumming spent weeks trying to convince senior officials to allow him enough independence to handle foreign intelligence with his own operatives while Kell handled domestic matters.

Finally, after endless arguments, Smith-Cumming was granted independence. He moved operations of the early agency to Ashely Mansions on Vauxhall Bridge Road. There, the Foreign Intelligence Service hid in plain sight. He set up a bogus address — Messrs Rasen, Falcon Limited — from which he could receive any mail.

Slowly, he recruited a cadre of agents. By 1915, Smith-Cumming had around 1,000 people working for him — each referred to by a letter to preserve secrecy. Agents including ‘B,’ ‘D,’ ‘L,’ and ‘K’ were soon scurrying around Germany and Western Europe, gathering information on German naval operations.

Smith-Cumming himself was known simply as ‘C,’ which he famously used to sign official reports in green ink.

Manfield Smith-Cumming And The Early Days Of MI6

Wikimedia CommonsThe early days of MI6 unfolded at 2 Whitehall Court, in London.

The early days of the Foreign Intelligence Service, which would eventually become the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and then MI6, were filled with both amateur moments and genuine successes.

The agents that reported to Mansfield Smith-Cumming were an odd mix. Since the spy agency wasn’t supposed to officially exist, it could be hard to get top-notch recruits. Instead, he oversaw the work of men like the slippery Sidney Reilly (later a model for James Bond) and a recruit the spymaster met, known only as “Major H.L.B.”

Wikimedia Commons/Federal Security Service of the Russian FederationSome sources list Sidney Reilly, one of Smith-Cumming’s spies, as inspiration for James Bond.

The “Major” claimed to have a ring filled with Peruvian poison that could kill in three seconds, a tie pin that was actually a camera, and an impressive knowledge of all the German spies in London.

Smith-Cumming noted that Major was “no doubt a blackguard (rascal), but probably is a clever one, and I should like to get something out of him.” He went on, grumbling, “All my staff are blackguards.”

The agents working under Smith-Cumming often made obscene requests — like an allowance for champagne. Other sources demanded fees for their services. A pair of Danish informers asked for £5,000 (£350,000 in today’s money) in exchange for information on German naval bases.

Smith-Cumming gave them just £10 — but still managed to get the information he needed out of them.

In its early years, the Foreign Intelligence Service stumbled along. One weapons expert got out of the wrong elevator in a French hotel, and become horribly lost. A researcher working for Smith-Cumming discovered that semen could be used as invisible ink — which led to the popular interagency joke that “every man his own stylo.”

The idea was later dismissed, because of the smell.

And as the spy agency developed, Mansfield Smith-Cumming began to build a reputation of his own.

He’d lost his son and part of his leg in a bad automobile accident in 1914 and encouraged rumors that he’d cut off his own limb with a penknife. Reportedly, Smith-Cumming would stab his wooden leg in front of potential new recruits. If they flinched, he’d remark: “Well, I’m afraid you won’t do” and dismiss them.

He also wore a golden monocle, carried a sword hidden in a cane, and zipped around the agency’s new headquarters at 2 Whitehall Court on a child’s scooter. He enjoyed trying out disguises and took photos of the ones he thought had worked well.

But the Foreign Intelligence Service under Mansfield Smith-Cumming enjoyed real successes under his guidance — especially when the outbreak of World War I put them to the test.

The Spymaster’s Successes in World War I

Until Smith-Cumming’s agents learned the extent of German losses at the Battle of Jutland, the press had portrayed it as a defeat for the Royal Navy rather than the stunning victory which it was.

Alongside the tomfoolery that defined the early days of MI6, serious work was getting done.

In the early days of the spy agency, Mansfield Smith-Cumming and his men had one target: Germany. His agents provided crucial information about the development of the Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet) and U-Boat construction programs.

In 1911, they were able to provide “a full and illustrated description” of the new heavy shell developed a year earlier, and “an account of its [impressive] performance against many varieties of armored targets.”

When World War I broke out in 1914 — thus confirming long-held British fears about German military might — Smith-Cumming and his spies were well-positioned to take action.

They notched a series of successes during the war. Smith-Cumming used his network of spies to discover that German naval losses at the Battle of Jutland were so devastating that the powerful German fleet would be out of action for the remainder of the war. This was a key victory for intelligence and a significant boost to public morale.

He also coordinated a network of 800 agents, men and women, codenamed La Dame Blanche. This army of agents in Belgium reported on the German troop movement, often using unconventional methods to pass on information. One agent, a midwife, was allowed to cross military lines — and carried her reports wrapped around the whale bones of her corset.

La Dame Blanche updated the British on an almost daily basis — providing invaluable insights into what the Germans were doing in Belgium.

After Germany’s defeat in World War I, the Foreign Intelligence Service continued to quietly toil away. Smith-Cumming oversaw the agency’s pivot from Germany to Russia. But by 1923, he was in ill health.

Captain Mansfield Smith-Cumming died on June 23, 1923, aged 64. But his signature lived on. To this day, his successors sign documents with the letter “C.”

The Shadowy Legacy Of Sir Smith-Cumming

Wikimedia CommonsThe M16 building today, in London.

After Mansfield Smith-Cumming’s death in 1923, his spy agency (renamed the Secret Intelligence Service in 1920, and MI6 at the start of World War II) continued to grow. But few in Britain knew about it. It wasn’t until 1994 that the British government even acknowledge that MI6 existed.

But MI6 has stepped more and more into the light in recent years — bringing Mansfield Smith-Cumming with it. In 2010, MI6 commissioned a book about its history to mark its centennial.

“Mansfield Cumming believed passionately in secrecy,” said Sir John Scarlett, the former SIS chief who’d commissioned the project.

“I am sure he would be surprised to see me here today presenting a history of his service. For MI6, this is an exceptional event. There has been nothing like this before and there are no plans for anything similar in the future.”

The book, written by Irish historian Professor Keith Jeffery, shed light on the inner workings of the secretive agency, and on the life of Smith-Cumming himself.

“I looked very hard for ‘bad stuff’,” Jeffrey noted. “In the end I found less evidence than perhaps we might have expected, certainly less evidence than I might have expected as the amateur espionage fiction buff that I was.”

One myth that Jeffrey was able to retire was that Smith-Cumming had cut off his own leg with a penknife following his automobile accent. The legend had outlived him, but the spymaster had in fact acknowledged that it was amputated during his life.

In 2015, a blue plaque officially commemorated Mansfield Smith-Cumming’s life and service to his nation. The plaque displayed at 2 Whitehall Court marked the building where he had once toiled as Britain’s preeminent spy chief.

Wikimedia CommonsThe blue plaque commemorating Mansfield Smith-Cumming’s service.

“I sense Cumming would share the delight I experience today, when I watch a small group of people, embodying the best of modern Britain, penetrate our enemies and disrupt their plans,” said Alex Younger, then the current “C” of MI6, at the unveiling of the plaque.

As for MI6 today? On the agency’s official website, it states that its most recent successes have been hidden from public view. However, the agency is “playing a major role in safeguarding the country’s people and interests.”

Now that you know the true story of MI6’s idiosyncratic first leader, read about Eddie Chapman, the criminal-turned-spy who was Britain’s secret weapon in World War II. Then, find out more about some of history’s most famous spies from across the globe.