She represented American on the global stage and became the country's most beloved dancer in spite of rampant discrimination.

Donaldson Collection/Getty ImagesMaria Tallchief.

Maria Tallchief’s talent and persistence allowed her to conquer stereotypes both at home and abroad and become a record-breaking dance star and America’s very first prima ballerina.

Maria Tallchief’s Early Life

The Osage tribe had been forced farther and farther from their homeland in modern-day Missouri ever since the Trail of Tears. They eventually settled in what is now Oklahoma and the American government had tried to ensure that the Osage were allotted the least-arable land in the state because they wanted instead to parcel out the best farmland to white settlers.

This would have sentenced the tribe to future poverty, if not for a dramatic twist of fate in 1894 when oil was discovered on Osage Territory. Practically overnight, the Osage were transformed from some of the poorest people in America to the richest.

Maria Tallchief’s father, Alexander Joseph Tall Chief, was just a boy when the oil had been found. By the time Maria was a child, he had so much property in Fairfax, Okla. that she felt “[he] owned the town.”

Tall Chief was a tall, handsome “full-blooded Osage” who “resembled the Indian on the buffalo-head nickel.” Maria recanted how women adored “Fairfax’s most eligible bachelor” and how when her mother (Ruth Porter, a petite woman of Scots-Irish descent) arrived in Fairfax to work as a maid for Grandmother Tall Chief, “there was an instant attraction between them.”

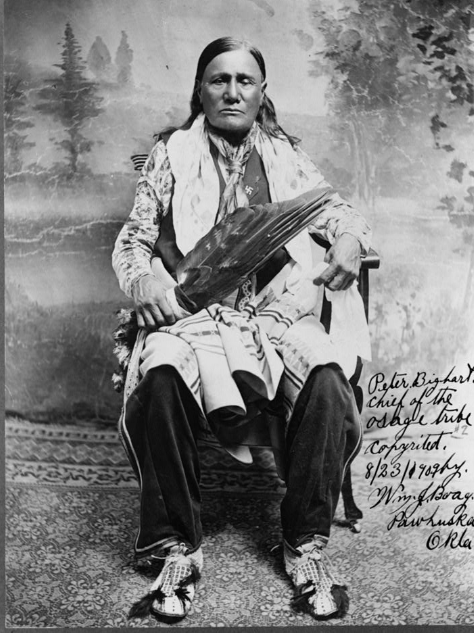

Library of CongressTallchief’s grandfather, Chief Peter Bigheart.

Elizabeth “Betty” Marie Tallchief was born on Jan. 24, 1925, in Fairfax, Okla. and her sister, Marjorie, followed 21 months later. Tallchief had her first ballet lesson when she was just three years old, in the basement of the Broadmoor Hotel in Fairfax.

She recalled being shocked when the teacher commanded her to “stand straight and turn each of my feet out to the side,” but she did as she was told and took her first steps down a path that would lead her to the most famous stages in the world.

But Maria Tallchief was musically talented all around. She had perfect pitch and played piano, initially wanting to become a concert pianist before ballet became the center of her life.

Indeed, Maria Tallchief’s mother became convinced that she was “grooming two musical dancing stars.”

Time would prove her right, however, the ballet teachers available in Fairfax possessed more greed for Tallchief’s money than actual schooling in classical ballet. One such teacher was so greedy that she reportedly almost caused Maria permanent physical damage. In 1933 the family decided to uproot and move to Los Angeles where Maria and Marjorie could study with real professionals.

John Franks/Keystone/Getty ImagesMarjorie Tallchief (left) and Maria Tallchief in costume at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, Dec. 8, 1960.

Although she found joy in ballet, the move to California was not without its difficulties for Tallchief, who described herself as a “typical Indian girl; shy, docile, introverted.” Her family was rich enough to afford a home in glamorous Beverly Hills, but Tallchief still experienced severe teasing because of her heritage.

Classmates would make “war whoops” whenever they saw her and ask if her father took scalps. The sisters could not even entirely escape hurtful (if perhaps unintentional) stereotyping in the world of dance. During their early recitals, Maria and Marjorie were made to perform a “traditional Native American dance,” although “it wasn’t remotely authentic” since “traditionally women didn’t dance in Indian tribal ceremonies.”

Photo by A. Y. Owen/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesBallet dancer Maria Tallchief donning ceremonial headdress during her hometown celebration.

Her Career In Ballet Takes Off

When she was 17-years-old, Tallchief left California for New York where she joined the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo.

The group had been formed from the ashes of the famous Parisian ballets russes and consisted mainly of Russian expats who had fled their homeland after the 1918 Revolution. At the time, ballet was still not widely popular among Americans (who generally performed tap or show-tunes) but had been a favorite pastime in Russia for centuries.

Russian ballerinas tended to look down on their American counterparts and Tallchief was not spared their disdain when she joined in 1942. One director even suggested Tallchief adopt the more Russian-sounding stage name of “Tallchieva,” which she refused to do, stating “Tallchief was my name and I was proud of it.”

She did, however, begin to go by Maria Tallchief, a more European version of her name.

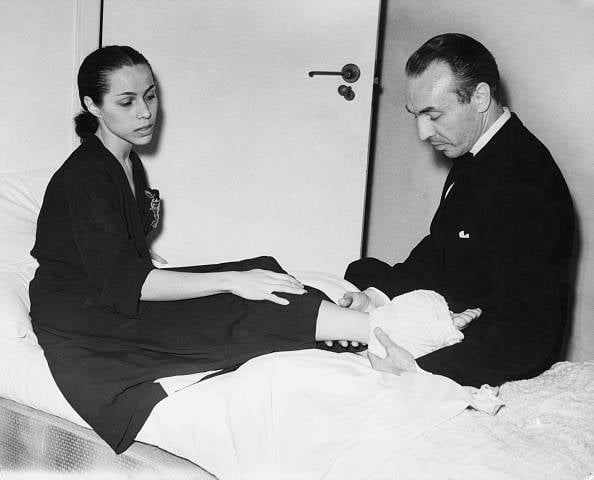

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesGeorge Balanchine checks on Maria Tallchief after she injured her ankle at the ballet’s debut performance in “Covent Garden” the night before, July 11, 1950.

In 1944, the Ballets Russes brought in choreographer George Balanchine to stage a couple of dances for their repertoire. The 40-year-old former dancer was another expat who had once performed for the last czar of Russia before being forced to flee to Paris, and eventually New York.

Balanchine was enthralled by all things Americana and when he met the stunning daughter of an Indian chief, he soon became enthralled with her too. Tallchief recalled how she was rather surprised when Balanchine proposed to her and later admitted that “passion and romance didn’t play a big part in our married life,” but Balanchine had found his new American muse and in 1946 the pair were wed.

That same year, Balanchine left the Ballet Russes to co-found his own company which would eventually become the New York City Ballet and remains today one of the most prestigious companies in the world.

Balanchine wanted to create an entirely new style of dance but ballet was steeped in such rigid tradition that the European ballet community was less than enthusiastic about embracing this new “American” style. Yet just a year later, Balanchine and Tallchief were presented with an opportunity that would rocket them both to stardom.

Paris And Stardom For Maria Tallchief

Paris had been the epicenter of the ballet world since the 17th century, but in the 1940s, the famous Opéra Garnier had run into some serious trouble. The opera’s director had been forced to step down in the face of accusations that he had collaborated with the Nazis.

This was a charge being flung at many of the city’s cultural elites, who became desperate to redeem their reputation after the war. In 1947, the opera hired Balanchine to produce a series of ballets in the hopes he could “breathe some new life” into the disgraced institution.

He arrived with his 22-year old wife in tow, whom he naturally cast to star in his production.

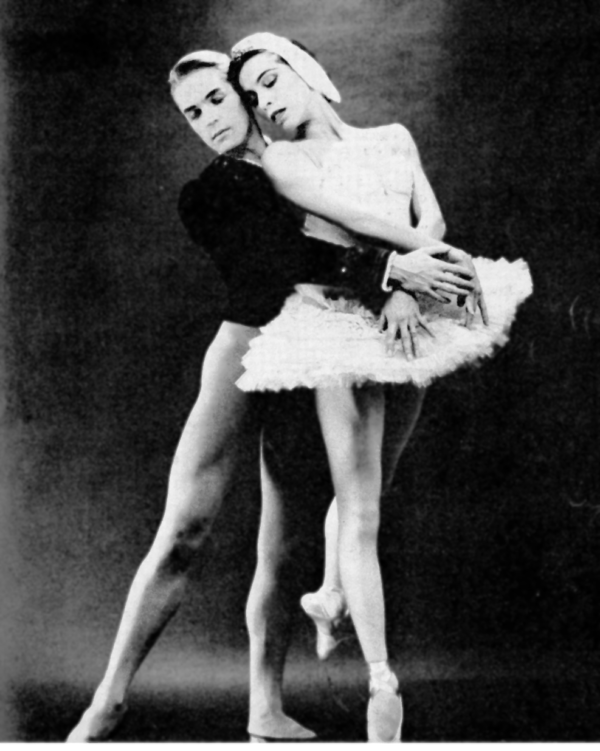

Wikimedia CommonsTallchief in costume for Swan Lake.

Any lingering European snobbery towards American ballerinas evaporated as soon as Maria Tallchief took the stage.

She was the first American to perform at the Opéra Garnier in the 20th century and audiences were dazzled by her combination of elegance and athleticism. However, although the public adored her, Tallchief still had to endure French headlines that blared “Redskin Dances at the Opera.” She would later explain that “I wanted to be appreciated as a prima ballerina who happened to be a Native American, never as someone who was an American Indian ballerina,” and although she was proud of her Osage heritage, could never entirely escape the stereotypes.

Together, Balanchine and Tallchief revolutionized the ballet. Balanchine’s choreography combined with Tallchief’s talents had not only turned European and Russian contempt for American ballerinas on its head but also popularized ballet in America.

When she premiered in “Firebird” in 1949, Tallchief recalled how she was shocked to hear the theater which “sounded like a football stadium after someone scored a touchdown” and how the dancers had been so unprepared for the enthusiastic reaction they hadn’t even rehearsed bows.

In 1954, Maria Tallchief debuted the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy in “The Nutcracker” to more rave reviews, which described how she danced “the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement.” Balanchine’s staging of “The Nutcracker” would turn the then-obscure ballet into one of the most popular and highest-grossing in the world.

Later Life And Legacy

Washington, DC, March 31, 1960.

Maria Tallchief’s list of achievements only continued to grow throughout her career. She became the highest-paid dancer in the world in 1955 and in 1960. The woman who had grown up on a small reservation in Oklahoma also became the first American in history to perform at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow.

In 1965 she left New York City Ballet and her marriage to Balanchine dissolved because he did not want children. Tallchief then briefly wedded twice more, first to Elmourza Natirboff and then to Henry “Buzz” Paschen with whom she had her daughter, Elise.

After retiring from dancing in 1966, Tallchief and her sister Marjorie opened the Chicago City Ballet in 1981.

Tallchief was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and received a Kennedy Center honor and the National medal of arts.

Her husband died in 2004, her daughter is now a poet. She passed away in April of 2013 at the age of 88.

After learning about Maria Tallchief, read about Ira Hayes, the Native American immortalized at Iwo Jima. Then, read about Ishi, the “last” Native American.