The Megatherium roamed South America for 5.3 million years before it went extinct — though some Indigenous people claim to have seen a similar creature in the Amazon to this day.

The year is 9,000 B.C. Humongous cave bears, saber-toothed tigers, and massive-antlered Irish elk roam the grasslands and forests of South America, but the biggest of all is the Megatherium, an elephant-sized ground sloth.

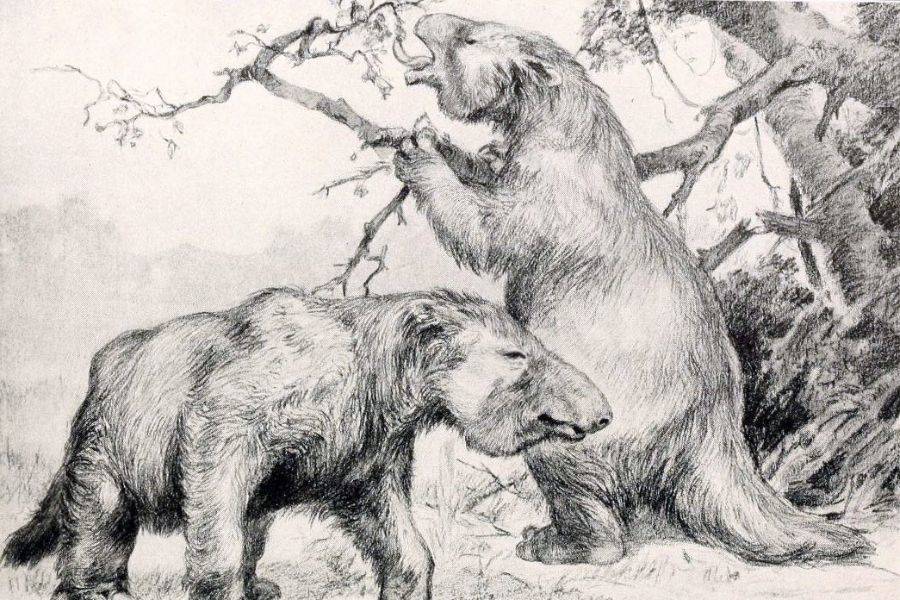

Wikimedia CommonsAn artist’s rendering of a Megatherium.

The Megatherium was one of the largest ground mammals ever to have existed. This giant ground sloth dominated the continent’s southern grasslands and lightly forested areas and was something of a king of the mammals for thousands of years before a mass extinction event wiped it from the planet. Or did it?

Rediscovering The Megatherium

It would not be until 1788 that the Megatherium would be seen again after the mass extinction event that wiped out prehistoric animals like the wooly mammoth and saber-toothed tiger, too.

It was then that an archaeologist named Manuel Torres discovered a rare fossil specimen on the banks of the Luján River in eastern Argentina. Though he did not immediately recognize it, he deemed it worth further study and sent it back to his base of study at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (The Spanish National Museum of Natural History) in Madrid, Spain.

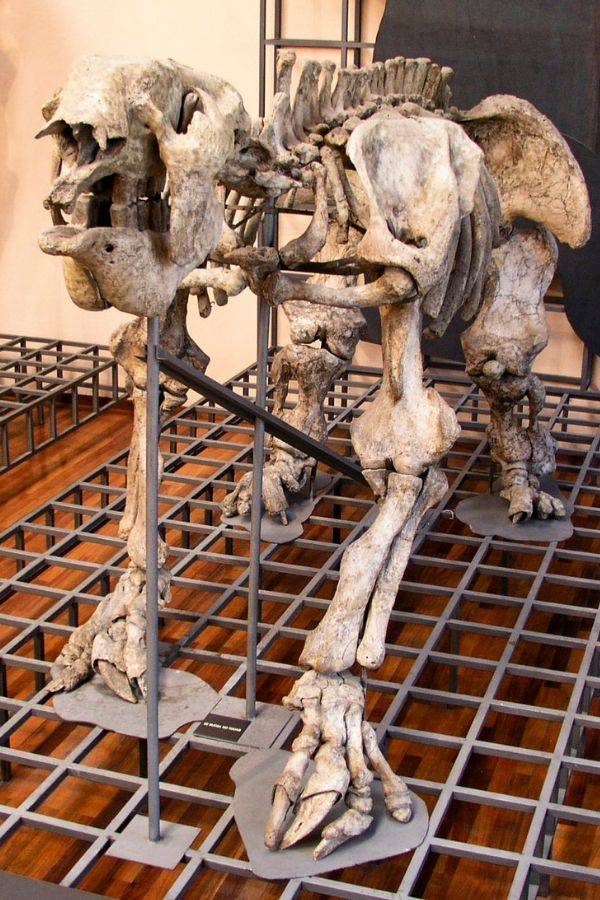

There, it was assembled into its most likely arrangement and mounted for display. A museum employee also created a thorough sketch of the animal to further study it.

Wikimedia CommonsThe original giant sloth specimen found by Manuel Torres that is on display in Madrid.

Before long, the fossil caught the eye of esteemed French paleontologist Georges Cuvier. Cuvier was intrigued by the sketch of the creature and used it to further explore its anatomy and taxonomy, and over time, he managed to create a more complete picture of the Megatherium’s history.

In 1796, just eight years after the Megatherium had been discovered, Cuvier published the first paper on it.

In this paper, Cuvier theorized that the Megatherium was a giant sloth, perhaps an early ancestor of the modern equivalent. Initially, he believed that the Megatherium used its claws to climb trees as modern-day sloths did. However, he later amended his theory and hypothesized instead that the sloth was much too large to climb trees and likely used its claws to dig subterranean holes and tunnels.

With this explanation, a picture of the Megatherium as it existed began to form; a sloth the size of an elephant, with giant, powerful claws, that lived mostly on and under the ground. With further study, scientists began to discover its habitat, diet, and reproductive cycle, and the picture became ever clearer.

The Megatherium likely lived across the continent of South America, from southern Argentina all the way to Colombia. Full grown, individual creatures likely weighed upwards of four tons — the weight of the average male elephant — making it the largest land mammal second only to the wooly mammoth.

It probably walked most of its life on four legs, though it is believed that it could stand on its hind legs in order to reach treetops and high foliage to feed its herbivorous diet. When it stood, the Megatherium would have been upwards of 13 feet tall.

Due to its immense size, it’s likely that Megatherium moved slowly like the sloths of today. It was likely one of the slowest creatures in its environment. In looks, it was quite similar to the modern sloth, though with facial characteristics of another one of its descendants, the anteater. In fact, it was in part this giant ground sloths resemblance to more modern creatures that got Darwin thinking about his theory of evolution.

The Megatherium lived in large groups, though individual fossils have been found in isolated locations such as caves. It gave birth to live young, as most other mammals do, and likely continued living in familial groups while their young matured. Due to the lack of predators – they outweighed (and could likely kill) saber-toothed cats and other small carnivores – they lived a quiet and probably diurnal lifestyle.

Further, the Megatherium wasn’t a picky eater.

The gigantic herbivores didn’t have to compete with smaller mammals for food as they had the advantage of height and procuring food from distances that smaller mammals simply couldn’t. They could tolerate and adapt to various types of plants as well as allegedly nibble on the occasional carcass, which allowed the Megatherium to migrate and thrive all over the continent — for 5.3 million years.

So what, or perhaps who, led to this resilient mammal’s extinction?

Wikimedia CommonsAnother artist rendering of two Megatherium.

Extinction And Possible Survival Of The Giant Ground Sloth Today

In roughly 8,500 B.C., the earth experienced a “Quaternary extinction event” during which most of the earth’s large mammals disappeared.

The Irish elk and saber-toothed tiger went extinct during this time as well as mammoths within the confines of continents, as some survived for several thousand more years in remote island areas. And, of course, the Megatherium went extinct during this time as well.

These giant ground sloths were thought to have survived in more remote areas for at least another 5,000 years following this extinction, though.

Scientists are still not entirely sure what accounts for this mass extinction as it does occur simultaneously with glacial-interglacial climate change. Instead, the extinction of the Megatherium seems more to have been the work of the emergence of mankind. Indeed, Megatherium fossils have been found with cut marks on them, suggesting that they were hunted by humans.

Whatever the reasons for their disappearance, scientists have long believed that the elephant-sized sloths have been out of commission for at least 4,000 years.

However, rumors of giant sloths living deep in the jungles of South America have emerged. Those who live in and around the Amazon rainforest have long passed down stories of a dangerous beast they call the “mapinguari,” a giant sloth-like creature who is over seven feet tall, with matted fur and large, sharp claws. They claim it tramples foliage and brush and roars out of a giant, second mouth on its stomach.

Stomach-mouth aside, the description of the mapinguari is actually quite similar to descriptions of the Megatherium, and indeed several drawings of the mapinguari are hard to discern from those of the Megatherium.

YouTubeArtist’s rendering of what the giant sloth-like mapinguari could have looked like.

Some experts have theorized that the initial mapinguari sightings many years ago may, in fact, have been Megatherium that survived extinction by sequestering themselves within the shelter of the rainforest.

As many theorize that the mass extinction event was, in part, caused by human invasion of their habitat, it would make sense that some could survive by avoiding populated areas. If the Megatherium truly did evade extinction, then the modern-day interpretation of the mapinguari is most likely an exaggerated report blown out of proportion through a generations-long game of telephone.

However, it could always be the case that the Megatherium truly did go extinct all those years ago and that the mapinguari, with its fetid breath and giant stomach-mouth, is truly roaming the Amazon and we are all in terrible danger.

After learning about Megatherium, the prehistoric giant sloth, check out these terrifying prehistoric creatures who weren’t dinosaurs. Then, read about what killed history’s scariest shark.