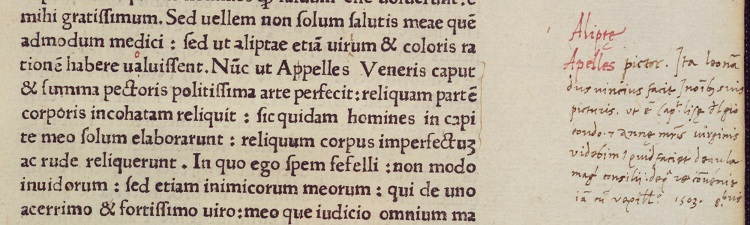

For the academics at University of Heidelberg in Germany, the mystery was solved in the mid-aughts, when someone discovered handwritten marginalia in a book from 1503 that belonged to one of Da Vinci’s friends. The notation reveals that Da Vinci was working “on the head of Lisa del Giocondo”.

Source: Wikimedia

But some scribbling in a book isn’t likely to convince those who believe other theories. Even with mounting evidence to prove that the woman was the wife of Da Vinci’s wealthy neighbor, it’s likely that future generations will continue to question the woman or man’s identity until something absolutely definitive is discovered.

And if it turns out to truly be Gherardini, the proof might only raise more questions: If the portrait was commissioned, why did the merchant never receive the painting of his wife? Da Vinci is believed to have started the painting in 1503 and worked on it for a number of years; it is also said that he carried the painting with him after that, adding touches possibly for more than a decade.

Source: Wikimedia

Instead of landing in Giocondo’s hands, the 16th century masterpiece was acquired by French King François I after Da Vinci was invited to work at the Clos Lucé near the king’s castle in Amboise. The small portrait painted on poplar wood has remained a national treasure in France and is one of the most recognized images in the world.

Every year, more than six million people view the piece at the Louvre, in Paris, where it hangs behind bullet-proof glass.

Source: Vital Statistics

The subject’s identity is not the only mystery behind Mona Lisa’s smile, which has been forever linked to the word “enigmatic.” Da Vinci used his self-taught technique of “sfumato” to blend the paint pigments, particularly around the corners of the subject’s eyes and mouth.

The technique is thought to have created an illusion of the “enigmatic smile” that disappears pending on the viewer’s vantage point. In the nanoseconds that it takes for the viewer’s eyes to shift from the subject’s eyes to the mouth, the smile seems to vanish.