"The government is so unjust with us... The government doesn't recognize that we built their freedom."

Peter Stackpole/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty ImagesTwo Navajo women stand near a piece of unearthed uranium in New Mexico in 1950.

For decades following the start of World War II, New Mexico’s history has been entwined with the U.S. government’s nuclear ambitions. From being ground zero of the first atomic bomb testing to the uranium ore mining boom beginning in the 1950s, New Mexico and its Navajo inhabitants have been at the center of it all.

And to this day, the state and especially the Navajo are suffering the dark consequences of the government’s actions.

The Associated Press reported that early findings from a recent study by the University of New Mexico have confirmed that Navajo women and babies continue to suffer from radiation exposure, even though uranium mining in the state ended more than 20 years ago.

The federally-funded study found that about a quarter of Navajo women and infants had high levels of the highly radioactive element in their systems. Among the 781 Navajo women who were screened during the initial phase of the study, 26 percent had concentrations of uranium that exceeded levels found in the highest five percent of the U.S. population. In addition, newborn Navajo babies with equally high concentrations continued to be exposed to uranium during their first year of life.

These dire findings came to light during a congressional field hearing in Albuquerque held by U.S. Senator Tom Udall, U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland, and U.S. Rep. Ben Ray Lujan — all from New Mexico.

“It forces us to own up to the known detriments associated with a nuclear-forward society,” said Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe and one of the first two Native American women elected to Congress.

Haaland and other elected officials heard testimonies from U.S. health officials, including Dr. Loretta Christensen, the chief medical officer on the Navajo Nation for Indian Health Service, and members from the Indigenous tribes who have been affected by the radioactive exposure related to uranium mining.

“The government is so unjust with us,” said Leslie Begay, a former uranium miner who lives in Window Rock, a town that sits near the New Mexico and Arizona border and serves as the Navajo Nation capital. “The government doesn’t recognize that we built their freedom.”

Begay, who attended the hearing with an oxygen tank by his side, talked about the lung issues he has dealt with since his mining days.

Haaland also shared her own family members’ experience with radiation exposure at the Jackpile-Paguate mine in Laguna Pueblo — the home of her tribe — which was once among the world’s largest open-pit uranium mines.

Loomis Dean/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty ImagesTwo Navajo people prospect for uranium on the Navajo Nation reservation. 1951.

The hearing reflects the federal government’s efforts in recent years to clean up the abandoned uranium mines scattered across the Navajo Nation territories and to determine the effects that prolonged exposure has had on generations of tribe members.

Navajo Nation territory spans across Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, and is home to more than 250,000 people. The uranium mines, meanwhile, covered 27,000 square miles within this territory.

During the Cold War era, private companies began coming in to dig up the precious metal which the government used to make atomic weapons. It’s estimated that at least 4 million tons of uranium were unearthed from the Navajo Nation lands.

According to a 2016 report from NPR, scores of Navajo people have died of kidney failure and cancer, which are both conditions linked to uranium contamination.

Research from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also showed uranium in babies born in the area years after the mining had stopped.

Maria Welch, a Navajo tribe member and researcher at the Southwest Research Information Center, told NPR she got involved in the previous Navajo Birth Cohort study because of her own family’s exposure to uranium.

“When they did the mining, there would be these pools that would fill up,” Welch said. “And all of the kids swam in them. And my dad did, too.” Not only that, the Navajo’s livestock also drank from those contaminated pools as well.

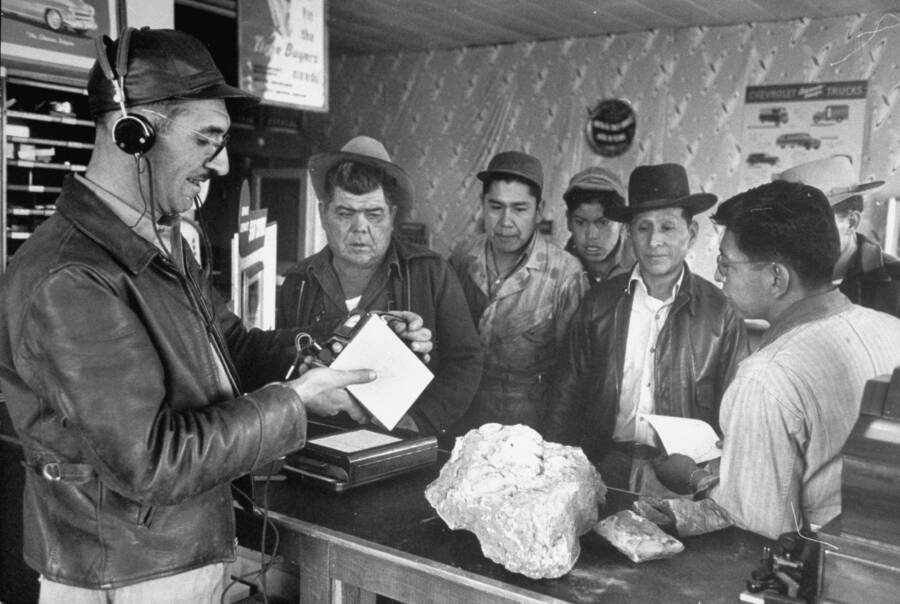

Peter Stackpole/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty ImagesAn inspector analyzes unearthed uranium in New Mexico as miners look on in 1950.

But as the Cold War died down, so did the U.S. government’s interest in uranium. The last uranium mining operation was finally stopped in 1998, and more than 500 of these mines were left abandoned. While the federal government has initiated clean-up efforts at these former mining locations, much of it has stopped due to lack of funding.

“They need funds,” Haaland said. “The job was not completed.”

Furthermore, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act only covers parts of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah that are downwind from nuclear testing areas in southern New Mexico. Now, Haaland and her colleagues are trying to push legislation that would expand radiation compensation to residents in New Mexico, including post-1971 uranium workers and those who lived downwind from the test sites.

And these efforts will only become ever more timely as groups continue to threaten the reopening of these uranium mines in New Mexico despite their devastating effects on the surrounding environment and people.

Next, read about how Canada finally identified 2,800 Indigenous children who died anonymously in state-run institutions and learn the tragic true story of Geronimo, the legendary Apache warrior.