Political ambition—or as some might call it when it comes to Richard Nixon, treason—prolonged the war in Vietnam for half a decade. Here's how it happened.

Richard Nixon (left) and Henry Kissinger (right) meet.

January 27, 2016, marks the 43rd anniversary of the formal peace in Vietnam. On that day in 1973, representatives of the United States finally reached agreement with North and South Vietnam to cease fire and withdraw the last American combat troops from the country. Two years later, North Vietnam broke the peace by invading South Vietnam and uniting the country by force.

The fall of Saigon isn’t the only tragedy associated with the end of the war: January 27th could have been the 48th anniversary of peace, if it hadn’t been for the ambition of two behind-the-scenes manipulators.

During the delicate negotiations for peace in the summer of 1968, then-Special Advisor to the President Henry Kissinger and presidential candidate Richard Nixon worked together, using classified information and covert communications channels, to undermine and frustrate President Johnson’s efforts to end the war—all for temporary political gain.

Days of Rage

Vietnam War protests were common at the time. Image Source: Flickr

By the summer of 1968, America had had more than enough of the war in Vietnam. The January Tet Offensive had pulled back the curtain and revealed an enemy who not only wasn’t beaten, but who had been gaining support in the heart of South Vietnam for years. Add to that the growing resistance to the draft and the dawning realization among policymakers that Vietnam was an endless mire, and peace negotiations offered themselves as an attractive, viable policy option.

A desire to negotiate was also driven by the perception among Washington insiders that the next presidential election, which was up for grabs following Johnson’s decision not to run, would hinge on the status of the war.

The math was pretty simple: Peace in Vietnam before the election would lead to Johnson’s chosen successor, Hubert Humphrey, winning in November, while continued war would mean victory for Richard Nixon, who was running on the promise of an honorable peace. Everything depended on reaching an agreement in Paris by the end of October, when Humphrey would either take credit for negotiating a ceasefire, or take the fall for losing it.

Kissinger and Nixon

Henry Kissinger (right) and Richard Nixon (center). Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Henry Kissinger was a very busy man in 1968. An operative associated with Nelson Rockefeller, a close confidante of Dean Rusk, an academic working for Harvard, and a Special Advisor to President Johnson, Kissinger had his hands full just with his official duties. But he also had access to secret information about the peace talks and personal contact with all of the most important people involved with the process. He was, therefore, uniquely well placed to wreck everything if he so chose.

Richard Nixon, meanwhile, was facing the fight of his political life. He had run a close race with Kennedy in 1960, narrowly losing in one of the closest elections in history, and two years after losing that race he retired from public life with an infamous “you won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore” case of sour grapes.

By 1968, however, Nixon had come roaring back into view. That summer, though he was trailing at the polls, he wasn’t out of the fight. Robert Kennedy’s assassination earlier that year had forced the Democratic Party to run a less appealing candidate whose campaign offered little more than the promise of bringing peace in Vietnam. A Nixon path to the White House became clear: Sabotage the talks and destroy the Democrats’ credibility when they talked about peace.

Signs of Trouble

President Johnson meets with President Nguyen Image Source: Wikipedia

Johnson got the peace talks off to a promising start. By 1968 the war had become deeply unpopular, and news that America was in a talking mood was greeted with optimism in Hanoi, the then-capital of communist North Vietnam. Saigon, meanwhile, was dubious. President Nguyen van Thieu worried that Washington, in its hurry to make peace, might sacrifice South Vietnam’s position against the North.

Throughout the process, diplomats worked closely with Nguyen to keep him informed and calm. Obviously, there would be no peace in Vietnam if the South didn’t agree to the terms, so Nguyen’s consent was crucial to any deal that could be worked out.

The first hint of trouble came during the summer peace talks. The South Vietnamese delegation stiffened its position and refused to make concessions to the North. In addition, South Vietnamese delegates started getting secretive and uncooperative with their American counterparts. President Nguyen refused to discuss this new reluctance with Johnson’s envoys, which threatened to make negotiations more difficult.

Chain of Betrayal

Paris talks soon backfired. Image Source: Flickr

At first, President Johnson was baffled by the sudden shift in South Vietnam’s position, which grew into a total boycott of the talks in Paris. By the end of October, news reached him that well-connected Wall Street financiers, namely Andrew Sachs, were investing in financial markets on their insider knowledge of Nixon’s plan to derail talks. Johnson ordered an immediate investigation by the FBI, which tapped several key figures’ phones and established that Nixon had been covertly encouraging Nguyen to hold out on the promise of getting a “better” deal if he, Nixon, won in November.

Declassified documents, including wiretaps, paint the picture of a long chain of conspirators. The cabal stretched from Paris, where Henry Kissinger was participating in daily negotiating sessions, to Nixon and his running mate, Spiro Agnew.

The pair passed word to China lobbyist Anna Chennault to inform the South Vietnamese Ambassador that the Johnson Administration was planning to settle on terms that would amount to a betrayal of Nguyen’s government. Apparently, a lot of people were in the loop: When the enraged President Johnson called Senate Republican Leader Everett Dirksen on a tapped phone and complained that the Nixon campaign’s actions amounted to treason, Dirksen’s response was, “I know.”

Nixon and Johnson meet. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

During Johnson’s phone conversation with Dirksen, he obliquely threatened to go public with what he had. Dirksen mollified the president by promising to call Nixon and discuss the matter. The next afternoon, November 3, Nixon called Johnson directly. During this call, in an effort to turn Johnson away from his threats of exposure, Nixon played the shocked innocent to perfection. From the recorded phone call:

“My God, I would never do anything to encourage… Saigon not to come to the table… Good God, we want them over to Paris, we got to get them to Paris or you can’t have a peace… The war apparently now is about where it could be brought to an end. The quicker the better. To hell with the political credit, believe me.”

It worked: Johnson kept the information secret. Two days after the uncomfortable phone call, Richard Nixon won a razor-thin victory over Humphrey, which almost certainly would not have happened if the Sunday papers had run front-page coverage of what Johnson and the FBI knew.

Repercussions

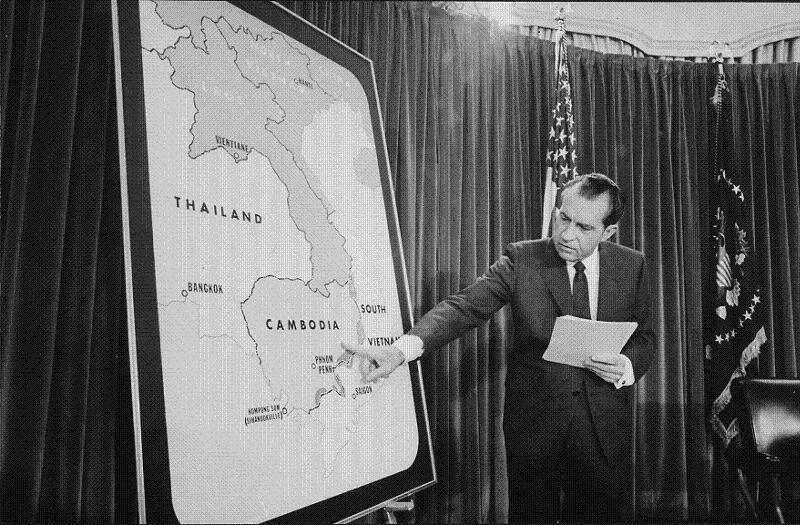

Under Nixon’s presidency, he carried out covert bombing campaigns in Laos and Cambodia.

Following the election, the Nixon Administration pursued a muddled Vietnam policy. Tough talk and heavy bombing mixed with back-channel negotiations and violent espionage made a hash out of America’s war effort.

Henry Kissinger, elevated first to the post of National Security Advisor and then to Secretary of State, oversaw a covert expansion of the war into Laos and Cambodia, as well as a secret bombing campaign that laid waste to Indochina and was run over the telephone line between Kissinger’s office in Washington and the U.S. embassy in Phnom Penh. The mass slaughter aided in the rise of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, and the famine that killed millions immediately after.

Kissinger’s Vietnam policy ended in 1975, with American diplomats hanging from the skids of helicopters evacuating the Saigon embassy.

Part of the Vietnam Memorial Wall. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

History is finished with all of the major players in this drama. Presidents Johnson and Nixon are dead, as are Spiro Agnew and Nguyen Van Thieu, who died in Boston, Massachusetts, in September 2001. Anna Chennault is still alive, aged 90, and lives a distinguished life in America. She has written several books, as well as chaired the boards of multiple nonprofits.

Henry Kissinger is, as of this writing, 92 years old and the author of at least 17 books. He is a prominent member of virtually every important foreign policy group in Washington, and his counsel is still sought as an expert in foreign affairs. He has been covered with honors and awards—most notably (and ironically) the Nobel Peace Prize, which his North Vietnamese counterpart refused—and has published his opinions in the Washington Post as recently as March 2014 as a thought leader on the Ukrainian crisis. Though his overseas travel is tightly constrained by potential war crimes indictments, particularly in South America, he remains unbothered in the United States, where there appears to be no serious threat to put him on trial for his crimes.

The Vietnam Memorial Wall complex in Washington DC hosts the names of every US serviceman who died in Vietnam. The names are listed alphabetically, indexed by date of loss. The wall records 58,195 American deaths, about 22,000 of which occurred after the Nixon campaign’s “October Surprise.” When peace finally came, in January 1973, the negotiated terms were substantially identical to what the positions had been in 1968.