Lasting just over a month in 1968, the Battle of Huế was one of North Vietnam's bloodiest attacks during the Tet Offensive — and it was later credited with souring the American public's opinion on the Vietnam War.

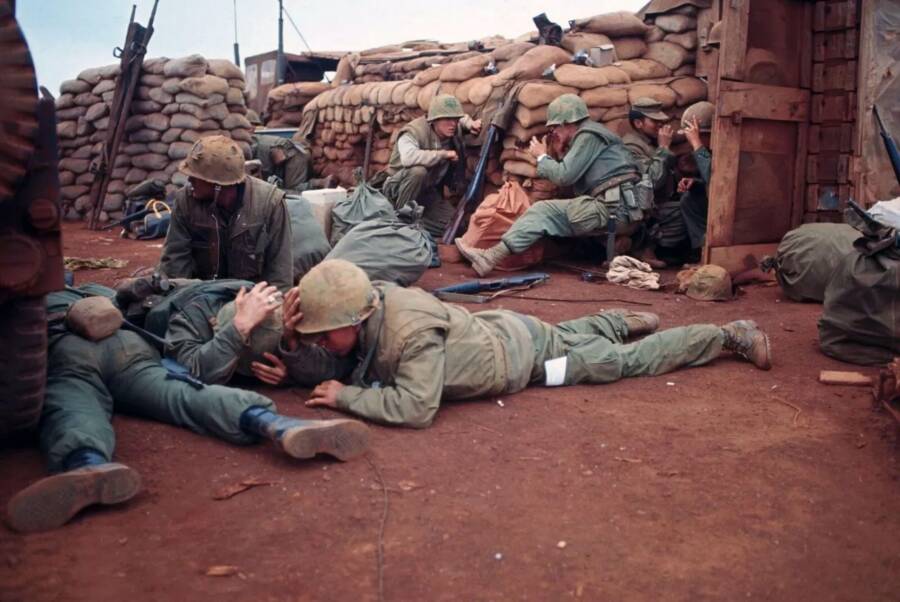

World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo U.S. Marines under fire during the Tet Offensive, which included the Battle Of Huế, in 1968.

America’s involvement in the Vietnam War was contentious, to say the least. Despite U.S. President Richard Nixon calling on the so-called “silent majority” who supported the country’s actions in Vietnam, the ongoing antiwar movement led to a series of massive protests across the nation that only grew more intense as the war dragged on.

But that movement wasn’t always so widespread. In fact, following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident — reports of unprovoked attacks on an American destroyer near North Vietnam that were later revealed to be a distortion of the truth by U.S. officials — many Americans supported the fight in Vietnam.

However, few expected America to be heavily involved in the war for nearly a decade, or that so many people would perish by the end. One estimate states that as many as 4 million people total died in the Vietnam War.

Public perception of the war in America underwent a major shift in January 1968, when the South Vietnamese city of Huế was attacked. The assault was part of the Tet Offensive, a coordinated series of North Vietnamese attacks on more than 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam.

The offensive produced some of the bloodiest battles of the war, but few illustrated the real human cost of the conflict as well as the Battle of Huế.

The Tet Offensive And The Attack On Huế

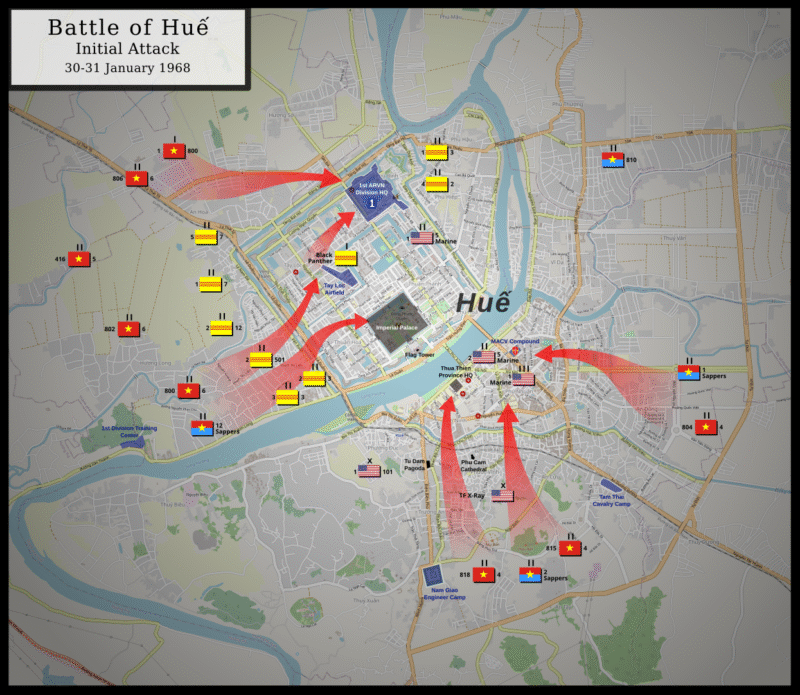

On Jan. 31, 1968, nearly 10,000 North Vietnamese (NVA) soldiers and Viet Cong (VC) troops launched a surprise assault on the former imperial capital of Huế (which is sometimes formatted as Hue).

They quickly seized control of most of the city, including the Citadel — a massive fortress housing the former imperial palace — catching South Vietnamese soldiers and American forces off guard.

Wikimedia CommonsA map of the initial attack during the Battle of Huế (or Hue).

Before that day, the city had been largely untouched by the ongoing violence of the Vietnam War. That said, it had proven to be an important strategic location for the American military's supply chain. Otherwise, Huế was mainly seen as a reminder of the country's past, before the Communist uprising in Vietnam and the tumultuous conflict that followed.

One account shared by the U.S. Naval Institute said of the city: "Hue justly deserves its title — 'Paris of the Orient.'"

Public DomainThe enthronement of Emperor Bảo Đại in the city of Huế in 1926.

In other words, Huế was widely believed to be a safe haven. The NVA and the VC didn't have enough men or resources to make significant headway into urban centers in South Vietnam, or so the South Vietnamese and the Americans thought. The Tet Offensive proved, however, that their assumptions about the northern forces were dead wrong.

The NVA and VC coordinated devastating attacks in South Vietnam, targeting dozens of major cities and towns. They planned to install their military throughout the south, believing it would lead to a significant uprising against the government of South Vietnamese leader President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu.

The timing was no coincidence either — Tet marks the first day of the Vietnamese lunar calendar. As such, many troops were set to go on leave to celebrate, leaving the south more vulnerable to an attack from the north. Some American troops had even suspected an offensive was coming, though they didn't believe it would be as brutal as the one that occurred.

According to historians Clark Dougan and Stephen Weiss, who wrote the book Nineteen Sixty-Eight, General William Westmoreland, commander of the American forces in Vietnam, had communicated to Washington that he was anticipating a "countrywide effort" from the NVA.

Despite his prediction, the higher-ups didn't think the NVA had the manpower, and no preparations were made for a wide-scale assault.

After the attack at the end of January 1968, the Americans and the South Vietnamese realized just how much they had underestimated their enemies.

Urban Warfare And The Fight To Reclaim Huế

Public DomainWounded U.S. Marines during the Battle of Huế (or Hue).

Once the NVA and the VC had overtaken the city, only a few pockets of resistance managed to hold out — namely, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) compound and some South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) positions.

Retaking the city proved to be a grueling endeavor, partly due to the urban environment. U.S. Marines and ARVN troops were forced to engage in intense house-to-house fighting, a rarity in the Vietnam War, which had primarily been fought in jungles and rural areas until that point. Combat was close quarter, booby traps were frequent, and the enemy was able to fortify itself.

The Citadel, in particular, provided excellent defense for the NVA.

"With its surrounding moat, high walls and stone towers, the Citadel provided ideal defensive positions," recalled photojournalist H.D.S. Greenway in a 2018 piece for The New York Times. "It took the Marines, operating from a compound across the Huong River, almost a month to recapture it."

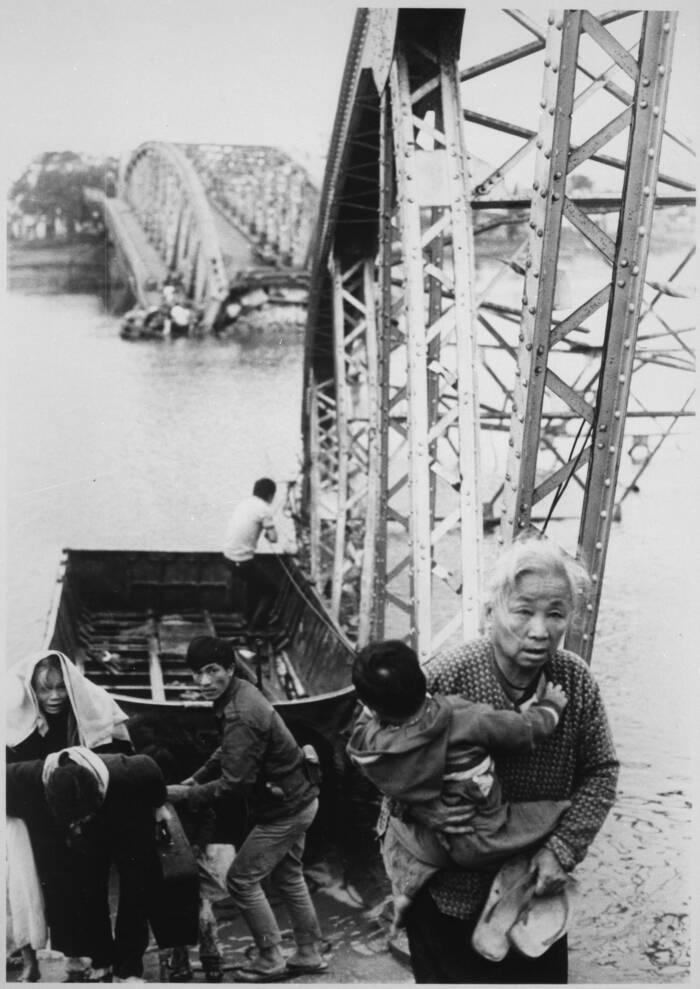

The situation was made all the more complicated by the presence of civilians, who were now trapped in the city amid the fighting.

"Civilians who had been hiding in their homes would appear from time to time and dash down the street, hoping to escape the battle zone," Greenway wrote. "Sometimes they made it. Sometimes they didn't."

Public DomainSouth Vietnamese residents of Huế (or Hue) fleeing the city during the battle.

In other parts of the country, the Tet Offensive had been an immediate failure. There was no massive uprising, as the North Vietnamese had hoped. The tide had quickly turned against them. They were soon expelled from most cities, and within two weeks, roughly 32,000 NVA troops were killed.

Huế was a different story, though. As journalist Mark Bowden detailed in his book Hue 1968, the North Vietnamese had taken the city in just four hours, yet it took about a month — and a bloody battle — to reclaim it.

But by late February, American and ARVN forces managed to breach and secure the Citadel, and the path to victory was secured. Victory couldn't hide the tragedy that had taken place, however, and the human cost of the battle made it clear to many back in the United States that the Vietnam War was nowhere near over, no matter what American officials claimed.

How The Battle Of Huế Shifted Public Perception Of The War In Vietnam

Public DomainThe Jeanne d'Arc church, damaged during the Battle of Huế (or Hue).

Prior to the Tet Offensive, many U.S. officials had portrayed the war as nearing a successful conclusion. The surprise attacks, and the prolonged Battle of Huế (or Hue) in particular, starkly contradicted these assurances. Media reports, especially the television footage showing the conflict and the aftermath, also dismantled the government's version of events.

Once the fighting had ceased by early March, the damage in Huế was assessed, and it was clear that the city was in shambles. The Battle of Huế had led to the deaths of an estimated 5,000 North Vietnamese soldiers, roughly 400 South Vietnamese troops, and about 150 U.S. Marines. But soldiers weren't the only ones who lost their lives during the battle.

Horrifically, North Vietnamese forces had conducted a systematic execution of civilians who they deemed to be enemies or threats to their control, with estimates ranging from 2,800 to nearly 6,000 deaths of unarmed victims.

When Allied troops unearthed mass graves in and around the city, they were shocked to find the dead bodies of thousands of people, with some fatally shot, others clubbed to death, and others simply buried alive. Chillingly, thousands more civilians were missing. Before long, the high number of civilian casualties led many to refer to the battle as the "Huế Massacre."

One eyewitness account, shared by the Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive at Texas Tech University, described the horror:

"...a squad with a death order entered the home of a prominent community leader and shot him, his wife, his married son and daughter-in-law, his young unmarried daughter, a male and female servant and their baby. The family cat was strangled; the family dog was clubbed to death; the goldfish scooped out of the fishbowl and tossed on the floor. When the Communists left, no life remained in the house."

Public DomainAmerican journalist Walter Cronkite interviewing Lieutenant Colonel Marcus Gravel during the Battle of Huế (or Hue).

Journalist Michael Herr, an Esquire correspondent who covered the Battle of Huế in a piece titled "Hell Sucks," detailed another disturbing sight:

"For me, though, the very worst dead was a Vietnamese who had been killed near a canal in southern Hue, on the road leading to the Hotel Company C.P. The very top of his head had been shaved off by a piece of debris, so that only the back of his scalp remained connected to the skull. It was like a lidded container whose contents had poured out onto the road to be washed away by the rains."

The battle and eventual massacre showed how brutal the fighting was, but it also revealed how different the reality of the war was from the American government's portrayal of it. American journalist Walter Cronkite visited the city for himself and famously declared, "It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate."

Contrary to what U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration had been saying at that point, there was no end in sight. That was, as Cronkite aptly put it, "the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion."

For the first time, many Americans had seen what the real cost of the Vietnam War was. It was a cost that many of them weren't willing to pay.

After reading about the pivotal Battle of Huế, learn about tunnel rats, the underground search-and-destroy soldiers of the Vietnam War. Then, go inside the fall of Saigon, the tragic final chapter of the Vietnam War.