For three months, Allied soldiers faced off against a relentless Imperial Japanese Army on the island of Okinawa in the last battle in the Pacific Theater.

When American troops landed on Okinawa in 1945, the European Theater of World War II was already closing its curtains. Many of the Nazi-occupied areas had been liberated by Allied and Soviet troops and Germany's surrender was just weeks away.

The Allies believed that capturing Okinawa would be integral to their success in ending the war in the Pacific Theater. Okinawa is the largest of the Ryukyu Islands located just 350 miles south of the Japanese mainland and without its airfields, the Allied forces believed they would be unable to successfully invade mainland Japan.

Over the course of 82 brutal days, a weakened Japanese army unsuccessfully defended Okinawa. And because the Imperial Army did not believe in surrender, it suffered massive losses fighting its soldiers to death. Indeed, Over 1,400 Japanese Kamikaze pilots entered the fray, ready to die for their cause because they knew that if Okinawa fell, the motherland was as good as defeated.

All the Allied forces had to do now was to take advantage of Japan's many vulnerabilities to end the war. In the Battle of Okinawa, Allied soldiers did just that in one of the last — and bloodiest — events of the war.

The Allied Invasion Of Okinawa

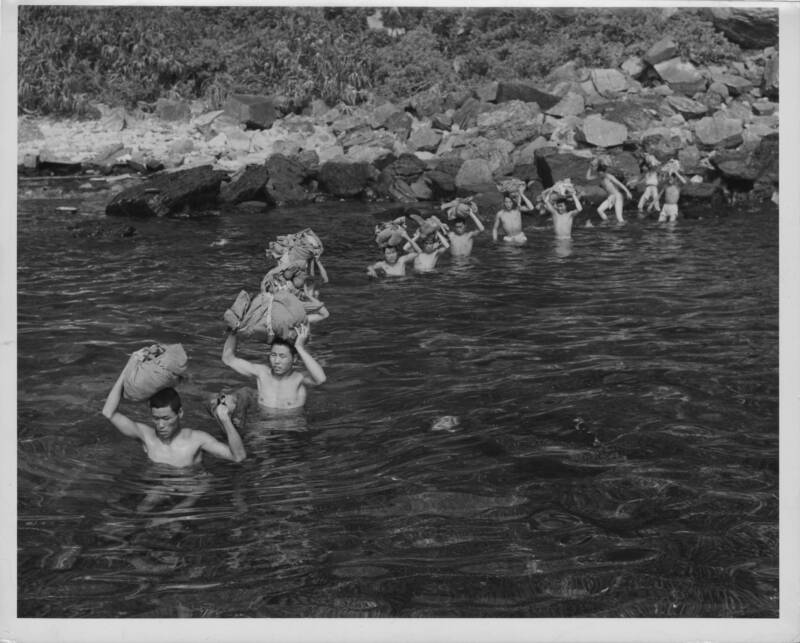

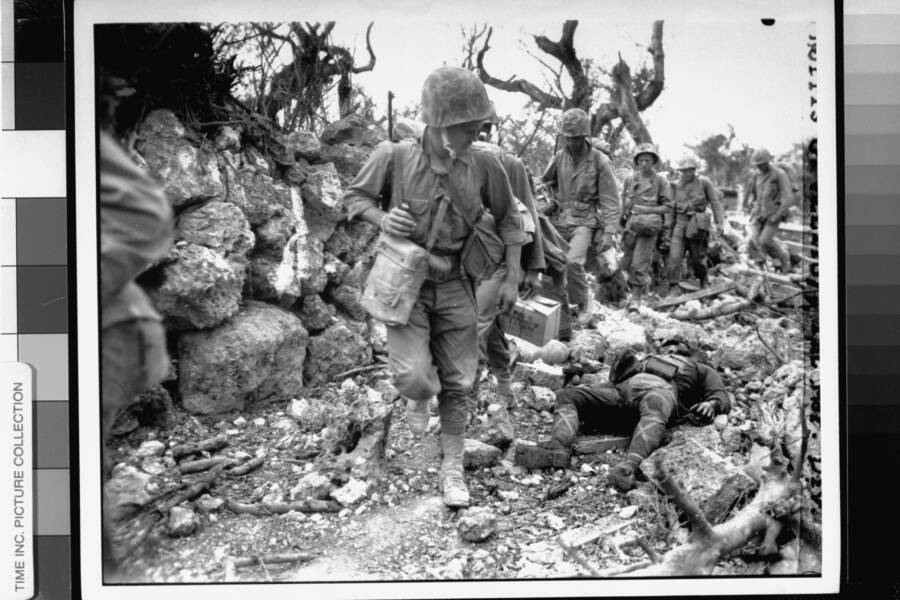

The Battle of Okinawa was the largest amphibious attack launched in the Pacific Theater. Allied generals told their soldiers to be ready for an onslaught, expecting the same kind of carnage their forces saw on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima and a casualty rate of 80 percent. But when over half a million men descended upon Okinawa, they found nobody defending it.

No Japanese soldiers met them on the shore. It was Easter Sunday — April 1, 1945.

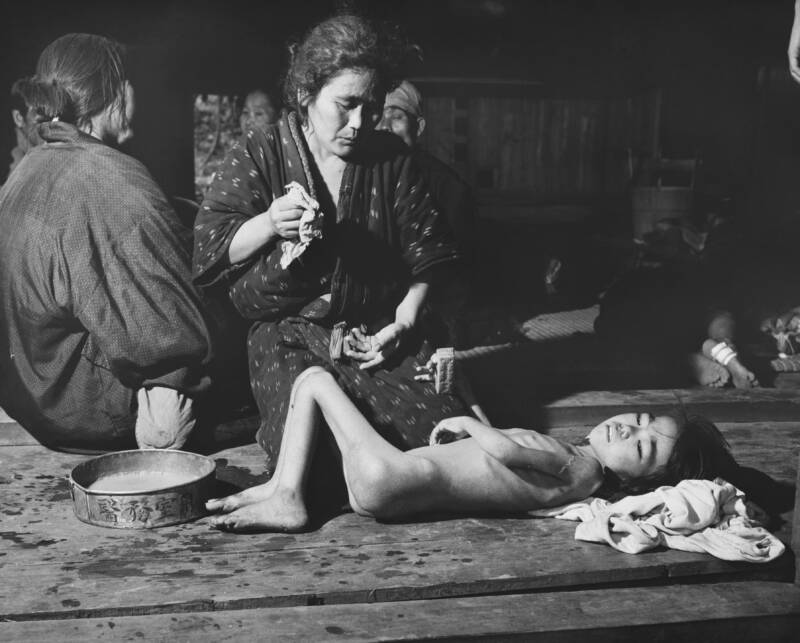

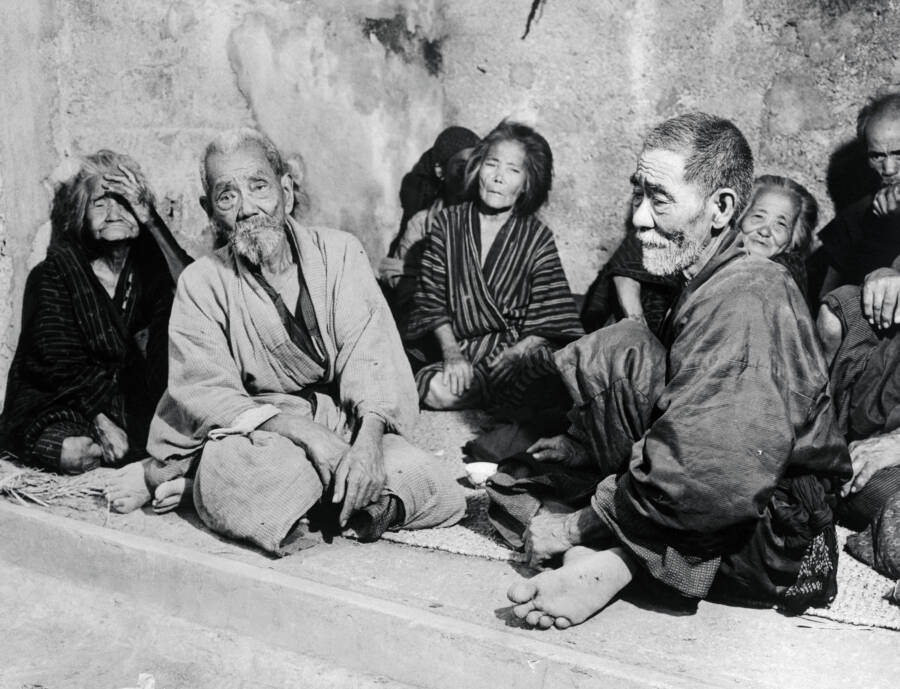

What the U.S. soldiers did find were civilians. Japan had effectively disowned the natives of Okinawa; mainland Japanese regarded Okinawans as second-class citizens and these natives paid the price for their homeland. As many as 150,000 civilians died during the Battle of Okinawa, many of them young boys recruited to fight.

It took a few days for advancing Allied soldiers to realize that the enemy they faced was hidden away. Japanese Lt. Gen. Ushijima Mitsuru hid his machine gunners in stone vaults in the hills. They lay in wait, conserving all their artillery for an inland fight at the Shuri Defense Line on the other side of the island.

The True Story Of Hacksaw Ridge

During the first several days onshore, the 10th Army swept across south-central Okinawa quite easily. Allied General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr. proceeded immediately with the next phase — capturing Shuri Castle on northern Okinawa.

However, the battle had only just begun, as Gen. Buckner soon realized that there were lightly guarded outposts protecting Shuri Castle.

While en route to the castle, the Americans encountered an attack at the Maeda Escarpment, often called Hacksaw Ridge, which occurred on April 26. The escarpment was located at the top of a harrowing 400-foot cliff, and the clash was absolutely brutal for both camps. Even more lives would have been lost were it not for the actions of one medic — and conscientious objector — named Desmond Doss.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesDesmond Doss shakes hands with President Harry S. Truman after receiving the Medal of Honor during a ceremony at the White House on Oct. 12, 1945.

Doss refused to carry a weapon into combat or kill because of his religion as a Seventh-day Adventist. Instead, he became a medic — assigned to the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion. Doss saved the lives of 75 wounded U.S. troops by dragging them to the edge of the escarpment and lowering them by a rope sling to safety.

The medic was wounded himself several times during this battle, always treating his own wounds and insisting that other injured soldiers take the available stretchers. Doss was finally struck by a sniper, shattering his arm and ending his involvement at Hacksaw Ridge. He will always be remembered for his heroism, and he received a Medal of Honor, a Purple Heart, and a Bronze Star for these efforts.

The Defeat At Shuri Castle

American troops encountered a stronghold when they reached Shuri Castle. During the first part of the Battle of Okinawa, Allied troops defeated a series of outposts en route to the castle. These were the battles at Kakazu Ridge, Sugar Loaf Hill, Horseshoe Ridge, and Half Moon Hill, which all saw huge amounts of casualties on both sides.

When Allied troops finally approached Shuri Castle, the ensuing conflict there raged on for nearly two months.

It was beginning to look like Shuri Castle was going to be the last stand for Japanese soldiers. However, on May 21, General Ushijima called a conference in the middle of the night in the command caves under the castle. He proposed three courses of action and ultimately the division and brigade commanders decided to retreat further south.

Wikimedia CommonsShuri Castle before the Battle of Okinawa.

This took the Allied forces by surprise as they'd also suspected Shuri Castle to be the last stand. They'd spotted groups of people traveling southward, but they dressed in white — the color that identified civilians.

After keeping an eye on their movements, Allied forces realized that Japan was retreating. On May 29, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines left its line to charge Shuri Ridge. The battalion commander immediately requested permission to cross into Shuri Castle. After approval, Company A of the 5th Marines marched toward the ultimate symbol of Japanese strength on the island.

But what Japanese soldiers lacked in number, they made up for in loyalty. The wounded either continued fighting until they die, or were stitched up and sent back out to the front line where they fought until their last breath.

The kamikaze pilot was Japan's most ruthless tactic. Well-trained pilots rained themselves onto Fifth Fleet naval ships, killing 4,900 Allied soldiers and wounding another 4,800.

Notable Casualties In The Battle Of Okinawa

For Japan, the battle of Okinawa was the first time they encountered an enemy at home during World War II. Most Japanese, soldiers and natives alike, believed that the Allied forces took no prisoners. They lived with the thought of capture as certain death and by a code that honored death over defeat or humiliation.

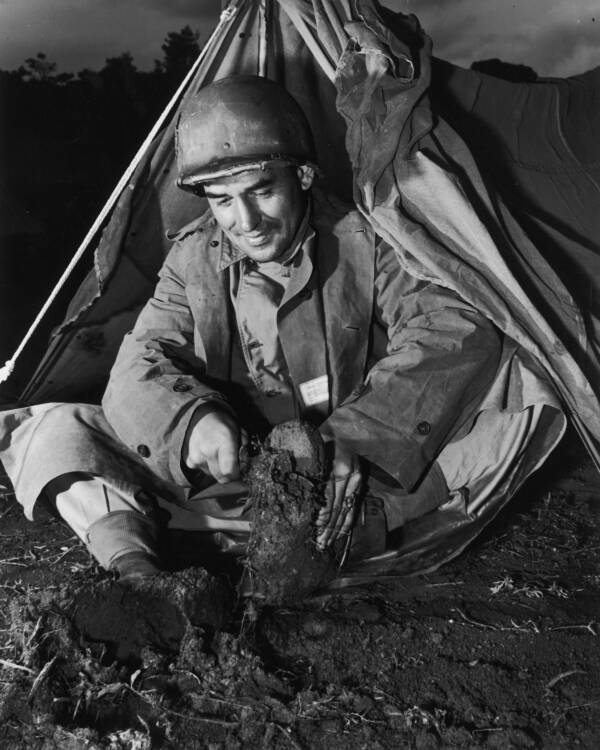

Because of this, the suicide rate for Japanese soldiers was extremely high. Outside of kamikaze pilots, many chose to take their own lives by ritual suicide called seppuku, which required they stab themselves with a sword through the gut, rather than surrender. Even Gen. Ushijima and his Chief of Staff, Gen. Cho committed suicide on June 22, 1945 — the last day of a war that they couldn't win.

Interestingly, Allied Gen. Buckner himself died after being hit by shell splinters just four days earlier.

The U.S. suffered another high-profile casualty: journalist Ernie Pyle. While he accompanied the 77th infantry division, Japanese machine gunners killed Pyle, a man whose war-time coverage made him a beloved correspondent.

The Battle of Okinawa saw the deaths of up to 100,000 Japanese soldiers and 14,000 Allied casualties, with 65,000 more wounded. However, the civilians of Okinawa still bore the highest death toll of the battle with over 300,000 deaths.

The Japanese Surrender

U.S. National ArchivesJapanese representatives aboard the U.S.S. Missouri (BB-63) during the surrender ceremonies, September 2, 1945.

After the Americans captured Okinawa, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur planned to invade the main Japanese islands in November. But growing reservations about Allied casualties gave way to another option.

On July 16, 1945, the U.S. detonated the world's first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert, 60 miles north of White Sands National Monument. Codenamed Trinity, the bomb was the result of the top-secret Manhattan project, which generated nuclear weapons.

The Allies thus issued the Potsdam Declaration, which demanded that the Japanese surrender or else face utter destruction. Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki told the press that his government was "paying no attention" to the ultimatum.

U.S. President Harry Truman called the prime minister's bluff. On Aug. 6, 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb named "Little Boy" on Hiroshima. Even then, the majority of the Japanese war council did not want to comply with the terms of unconditional surrender.

Japan's desperate situation only worsened after the USSR attacked Manchuria in China and overwhelmed the Japanese troops stationed there. Then, the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki on August 9.

The Japanese Emperor Hirohito called together the supreme war council. An emotional debate ensued, but he backed a motion by Prime Minister Suzuki to accept the Potsdam Declaration.

On Sept. 2, 1945, the Japanese signed their surrender aboard the U.S.S. Missouri.

General MacArthur stated that the opposing factions did not meet "in a spirit of mistrust, malice or hatred but rather, it is for us, both victors and vanquished, to rise to that higher dignity which alone benefits the sacred purposes we are about to serve."

However, the U.S. naval ship had bombs on board and at the ready — just in case.

Next, read from the diaries of Japanese kamikaze pilots. Then, read more about the fighting in the Pacific Theater, the horror show history wants to forget.