Hitler had German commandos trained to infiltrate allied territory in a Trojan Horse mission that caused confusion and chaos among real American soldiers.

Photo By George Silk/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty ImagesGerman soldiers surrender during the Battle of the Bulge, the final major German offensive of World War II during which Operation Greif took place.

In a final grapple against the Allied powers around Belgium, Hitler devised a special operation so secret that allegedly many German officers remained unaware of its existence until the day of its launch. The plot, dubbed Operation Greif, involved German soldiers disguised in Allied uniforms to cross into Allied lines and wreak havoc.

If it sounds like a plan just crazy enough to work, it wasn’t exactly. While Operation Greif did succeed in amassing paranoia and confusion in Allied territory, it didn’t strengthen Hitler’s last-ditch effort at the Battle of the Bulge.

Hitler’s Last Stand

Although the success of D-Day had allowed the Allies to establish a foothold in Europe, the situation on the continent was far from secure. One of the main problems was that supplies could only cross the channel at Normandy and that the further the British and Americans pushed into the interior, the thinner their supply lines became stretched. Meanwhile, across the Rhine, Hitler plotted one dramatic last stand.

Hitler intended to amass enough of his own forces in Western Europe to mount a massive counter-offensive against the thinly-spread Allied forces in the Ardennes. His ultimate goal was to slice through the Allied lines and retake Antwerp and its vital port. He first wanted to capture and then destroy the Meuse river bridges.

The plan’s only hope of success lay in taking the British and Americans by complete surprise. Hitler’s plan was therefore kept so confidential that many German officers remained unaware of its existence until the day of its launch.

Even the officers who did know about the plan were skeptical about its chances for success, with one grimly commenting, “the entire offensive had not more than a ten percent chance of success.” Hitler, however, was not one to leave things merely up to chance and he had just the man to sway the odds in his favor.

Heinrich Hoffmann/ullstein bild/Getty ImagesOtto Skorzeny.

In October of 1944, SS Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny was summoned by Hitler and briefed on what the Führer described as “the most important [assignment] of your life.” Skorzeny already had an unsavory reputation among the officers of the German Army who regarded him as a “typical evil Nazi” and “a real dirty dog.”

Perhaps that’s why Hitler entrusted the SS officer with training small groups of German commandos to be sent behind Allied lines in American uniforms to sow chaos before the planned invasion of the Meuse bridges. Skorzeny was, indeed, particularly suited for this task. Skorzeny had no qualms in violating international agreements nor in risking the lives of his men.

Sending disguised soldiers behind enemy lines went beyond the bounds of conventional warfare, so when Skorzeny sent out orders demanding POW camp commandants to strip their American prisoners of their uniforms in the middle of winter, many of them refused, stating it violated the Geneva Convention.

The Convention also stated that soldiers captured behind enemy lines wearing enemy uniforms forfeited their rights as POWS and could be summarily executed. But Skorzeny would do anything it took for “the last remaining chance of concluding the war favorably.” Hitler granted Skorzeny unlimited powers and preparations for Operation Greif or “Griffin”.

Wikimedia CommonsA group of Germans who had been captured wearing American uniforms are executed during the Battle of the Bulge.

German soldiers who could speak English soon began receiving mysterious orders to report to a special training camp for “interpreter duties.” Upon arrival, they were questioned in English by SS-Officers before signing a pledge to secrecy that ominously concluded with “breach of the order is punishable by death.” These soldiers would make up the top-secret 150th Panzer Brigade who were based at the heavily-guarded Camp Grafenwöhr.

Operation Greif was intended officially to destroy bridges, ammunition dumps, and fuel stores in Allied territory while simultaneously passing along false orders to any U.S. units the Germans encountered, and reversing road signs, removing minefield warnings, and blocking off roads with fake warnings. Commandos were also expected to stunt U.S. communications by cutting telephone wires and radio stations.

Operation Greif would only succeed in some of these goals.

Training Germans To Be Americans

The Allies allegedly heard about the “top-secret” plan but ignored it under the pretense that it was false information.

Meanwhile, the participants of Operation Greif underwent heavy if somewhat unusual training at Grafenwöhr. In addition to close-quarter combat and demolition training, the commandos spent at least two hours every day improving their English, watching movies and newsreels to perfect the American accent and pick up idioms and slang. The utmost confidentiality was required, and one soldier was even executed for writing home with too much information on the operation.

Keystone/Getty ImagesA captured Wehrmacht soldier identifies an SS trooper as one those who shot US Army prisoners in Malmedy, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge.

They were also taught to pick up American customs that could otherwise give them away as German. These cultural nuances ranged from learning how to “eat with the fork after laying down the knife” and how to “tap their cigarette against the pack in an American way.” The men saluted in the American style, ate American k-rations, and were given their orders in English, yet such was the secrecy of their mission that they were kept in the dark about what they were training for.

Many of the men came to believe that they were certainly passing for Americans, but Skorzeny had more grim opinions. “After a couple of weeks the result was terrifying,” Skorzeny wrote.

Of the 2,500 men he had recruited, only about 400 could speak colloquial English and only 10 were fluent. Skorzeny lamented that they “could certainly never dupe an American—not even a deaf one!”

The brigade was also short 1,500 American helmets and American guns and ammo. Many of the uniforms supplied were British, Polish, or Russian, or had bloodstains or POW markings. Skorzeny procured only two American tanks and the rest of the equipment was German. Skorzeny conceded that only “very young American troops, seeing them from very far away at night,” would be fooled.

Despite this, on Dec. 16, 1944, the Germans launched their full-fledged counter attack. The Allies had been caught completely unaware and, just had Hitler had hoped, the Germans were able to drive deep into their lines. Two inexperienced and unprepared American divisions were suddenly faced with an onslaught from more than a quarter-million German troops. Panic and chaos reigned as the Allied high command desperately tried to form a defense plan. The American line, however, was stretched but not broken, creating a “bulge” from which the battle would take its name; the Battle of the Bulge.

On the second day of battle, American military police stopped a jeep carrying four soldiers near a bridge and demanded their passes. The four men spoke English with American accents and were wearing American uniforms, but were unable to produce the proper paperwork.

The suspicious MPs then searched the vehicle and discovered concealed weapons, explosives, and swastika emblems. Under interrogation, one of the commandos of Operation Greif claimed that they had been dispatched with orders to “penetrate Paris and capture General Eisenhower and other high ranking officers.”

Wikimedia CommonsA German tank disguised as an American tank during Operation Greif.

This deeply rattled American forces who then plundered into paranoia.

Chaos Behind the Lines

The discovery of the soldiers involved in Operation Greif “provoke[d] an American over-reaction bordering on paranoia.” Horrified by their oversight regarding the German attack, Allied Counter-Intelligence was determined to not take any further risks. General Eisenhower’s security was increased to the point that “he almost found himself a prisoner” and roadblocks were set up on nearly every road. American soldiers were instructed to “question the driver because, if German, he will be the one who speaks and understand the least English.”

Neurotic American soldiers soon established a set of security questions sometimes with unintentionally humorous results. The participants in Operation Greif had been trained in American slang so well that checkpoint guards came up with questions they thought only a fellow American would know.

Popular categories included state capitals, baseball, and movie stars, although they could range from “What is Sinatra’s first name” to “What is the name of the President’s dog?”

These checkpoint questions failed to account for British soldiers, who suddenly found themselves at a severe disadvantage. When reconnaissance officer David Niven found himself faced with a guard demanding “Who won the World Series in 1940?” all he could do was reply “I haven’t the faintest idea.” American officers, even the highest ranking ones, were not immune to mistakes either. Brigadier General Bruce Clark was once arrested for a half hour after he gave a wrong answer about the Chicago Cubs and the overexcited guard exclaimed: “Only a kraut would make a mistake like that!”

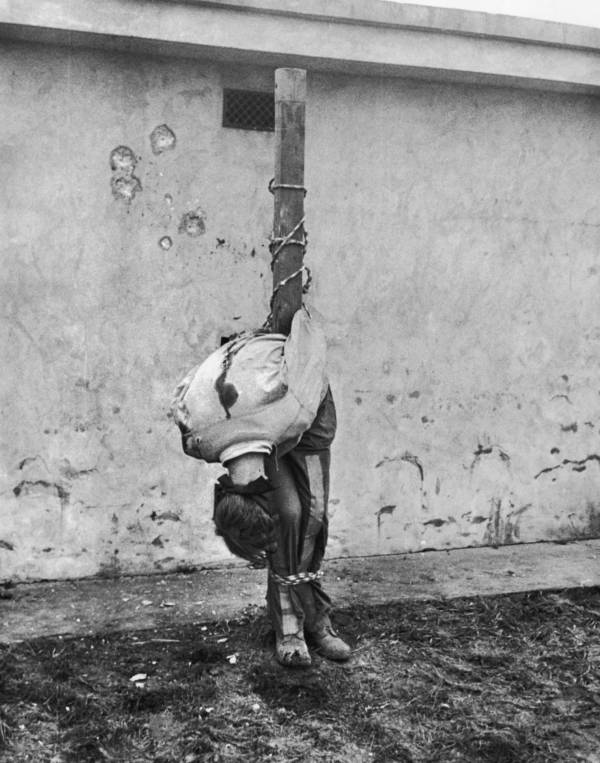

John Florea/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesGerman soldier executed by an American firing squad on Dec. 23, 1944.

Aftermath Of Operation Greif

Although Operation Greif did indeed succeed in sowing chaos among the Americans, it failed to meet its ultimate goal. The Americans put up an unexpectedly fierce resistance and the commandos were never able to destroy any bridges or communication lines. Any of the Germans caught wearing American uniforms were promptly tried and sent before a firing squad.

The Allied high command was particularly fierce in its treatment of the captured commandos. American soldiers were instructed “Above all don’t let them take off their American uniform” and when 16 of the prisoners sentenced to death appealed to General Bradley, he refused.

The 150th Panzer-Brigade was withdrawn from the Ardennes offensive by the end of December and by January 1945, the Americans had crushed the last major German offensive of the war. Operation Greif had failed to do little more than confuse American troops for a time.

After this look at the failed Operation Greif, read about how the Norwegians may have ultimately saved us all from life under Nazi rule through Operation Gunnerside. Then, check out some of the most absurd Hitler death conspiracy theories.