Born into slavery, Bill Richmond managed to get to England where the free man became the country's biggest and potentially first, African-American athletic celeb.

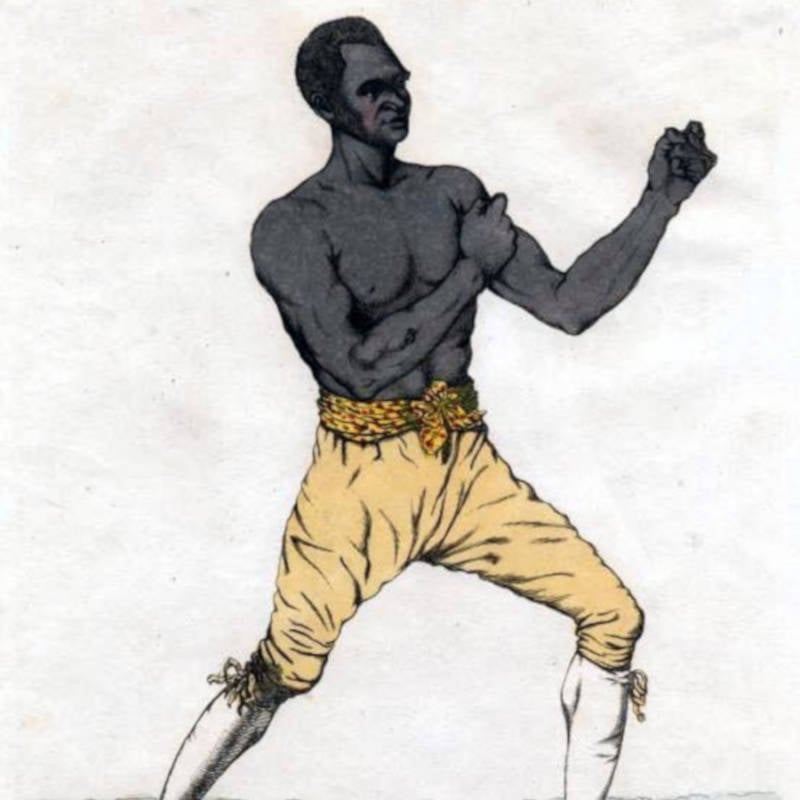

Wikimedia Commons Bill Richmond in a boxing pose, circa 1810.

Bill Richmond was born into slavery in New York in 1763 — until he gave himself a fighting chance to win his freedom. Richmond fled to the U.K. where he fought professionally against racial bigotry: and become one of the biggest sports celebrities of his day.

Bill Richmond, Born A Fighter

Bill Richmond was born on Staten Island, New York and grew up in the household of Richard Charlton, a wealthy rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. Charlton had a residence in Richmond on Staten Island, and it is said that that’s where the youngster took his last name.

Luke G. Williams, Richmond’s biographer, surmised that Charlton could have been the boy’s father. A full century before the U.S. Civil War divided a nation from North to South, slavery was widespread in the English colonies and Charlton, as a minister and a man of the cloth, owned his own slaves. Little more is known about how Richmond lived with Charlton.

Regardless, the minister had 13 slaves total and rather than freeing them upon his death, Charlton bequeathed them to his children. Although it wasn’t field work, Richmond likely spent time sweeping, mopping, and performing chores around Charlton’s house. But a chance encounter in the summer of 1776, at the age of 13, changed Richmond’s life forever.

Brigadier General Hugh Percy commanded British forces in New York at the beginning of the American Revolution. The summer of 1776 was a tipping point for the Colonials, as the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to sign the Declaration of Independence that year and find themselves a sovereign country. New York, thus, became a port of vital interest to Britain. As a rapidly growing urban center, New York could provide unique insight and control to the British. It was Percy’s job to keep his troops at the ready there in case violence broke out.

Wikimedia Commons Brig. Gen. Hugh Percy, Bill Richmond’s benefactor.

Anecdotes vary as to how Percy and Richmond met, but the most likely theory is that Charlton, a British loyalist, invited Percy to visit him on Staten Island. Percy admired the young Richmond’s manners and conduct. Indeed, surviving to 13 as a slave no less, was something of a feat. His physical presence was only matched by his intelligence.

Another story tells of how Richmond fought for his pride and honor. Allegedly, Percy came into a rowdy tavern where his men were drinking. At one point, a melee broke out, but a lone figure defended himself at the center of it all: 160-pound, 13-year-old Bill Richmond.

Percy was duly impressed with the boy’s fighting spirit. Regardless of how monumental the meeting or not, either anecdote leads to the one conclusion that Percy somehow persuaded Charlton to sell the young man to him.

As pugilism, also known as boxing or prizefighting, was one of the biggest sports in Great Britain and perhaps only bested by horse racing during the 1700s, the general arranged such fights for Richmond to entertain his houseguests. His opponents were some of the toughest British soldiers Percy could find.

Life In England

Although Percy commanded British forces in America, he was pro-abolitionist. He thought slavery was distasteful, vile, and inhumane. However, he couldn’t tell wealthy loyalists in America what to do. He needed their support to try to win a war.

Instead, Percy did what he could for Richmond. In 1777, Percy sent the young Richmond to England, where “The Duke [Percy] finding Bill to possess good capacity, and being an intelligent youth, had put him to school in Yorkshire.”

The teenager received a scholarship to attend the school and there he made good progress. When he was old enough, Percy arranged an apprenticeship for the boy in cabinetmaking for a master in York.

Even though he was under the tutelage of a well-respected British Army officer, Richmond faced an uphill battle against class and race. English aristocracy and society were predominantly white. Percy even risked alienating himself from his own social circles by bringing Richmond over to England. Nevertheless, Percy and Richmond endured.

Richmond later married a local white English woman named Mary Dunwick with whom he had several children in the 1790s. As cabinetmaking was a prized art in England for the wealthy who wanted beautifully ornate cabinets for their homes, Richmond continued to break the racial mold. Black people weren’t usually apprenticed or cabinetmakers in the late 1700s and so Richmond stood out from everyone, and it drew attention to him — sometimes unwanted.

Pierce Egan, a journalist in Yorkshire in the 1790s, said he witnessed five fights involving Richmond, the cabinetmaker’s apprentice. At least three fights originated from insults hurled at Richmond. One such fight happened after a white person called Richmond a “black devil” for being with a white woman, presumably his wife.

By 1795, Richmond moved to London. There, he met Thomas Pitt, the Lord of Camelford. Pitt was a former naval officer who loved boxing and prizefighting. He hired Richmond as an employee and household member where Richmond presumably coached the Lord in fighting.

Wikimedia Commons An engraving of Thomas Pitt, circa 1805.

But their relationship appeared to be more than merely professional. Pitt also understood injustice. He felt he was unjustly and harshly punished by Capt. George Vancouver, commanding officer of the HMS Discovery. Together, Pitt and Richmond attended prize fights and tussled with each other in the bare-knuckle brawls of Pugilism. There were no boxing gloves then and matches may have lasted for several hours.

Prizefighting was more akin to current-day MMA or UFC bouts instead of boxing with 1-pound gloves. As such, pugilism was brutal and bloody. Whereas Pitt would go into a fight filled with swashbuckling swagger, Richmond learned to dodge and sidestep onrushing opponents.

But Richmond did not experience a professional fight until he was 36. In 1804, he came against the infamous and undefeated fighter George Maddox. Though the match lasted nine rounds, Richmond did not win. But his effort was in itself a triumph. Maddox usually won bouts after a few rounds and for someone — and a rookie fighter, especially — to hang nine rounds in the ring was unfathomable.

Richmond’s success and talent came from his style. As an intelligent and strategic fighter, Richmond would become second-to-none.

“The older he grows, the better pugilist he proves himself…He is an extraordinary man.”

Richmond’s Professional Record

Richmond didn’t become a professional fighter until he was in his 40s. Even more remarkable, he won matches well into his 50s. The year after his spar with Maddox, Richmond defeated a Jewish boxer known as “Fighting Youssep.” This contest put him on the map and he was soon matched with boxer Jack Holmes, which would lead him ultimately to his second and final loss against an opponent nearly 20 years his Junior: the incomparable Tom Cribb.

Indeed, Richmond’s second loss was, perhaps, one of the greatest bouts in boxing history for its time.

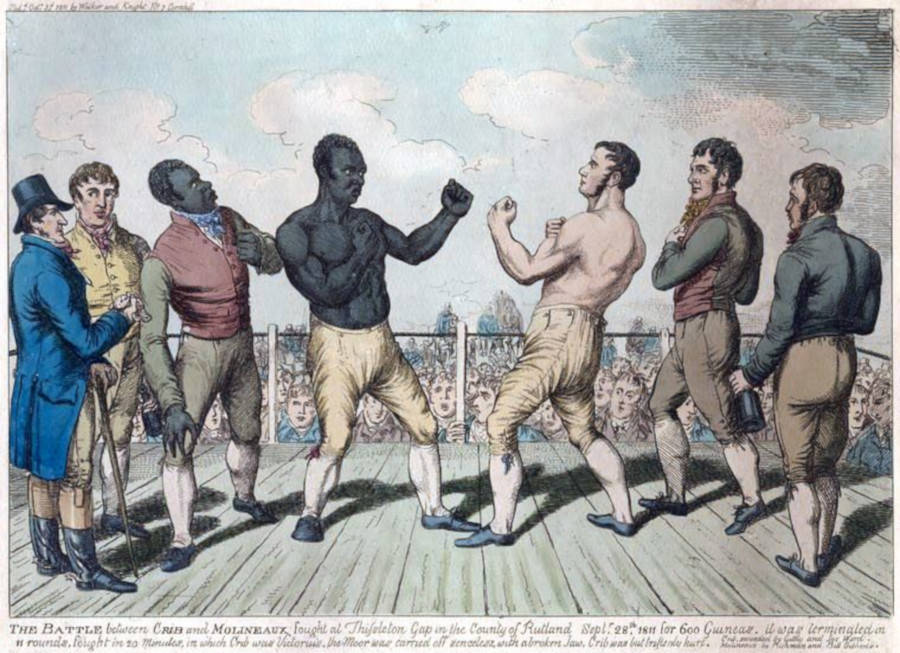

Wikimedia Commons Tom Cribb versus Thomas Molineaux in 1811. Richmond is standing behind Molineaux.

Besides Maddox as a beast in the ring, there was Tom Cribb. He and Richmond battled for 90 minutes in 25 rounds with neither man giving an inch. Cribb eventually knocked out the 42-year-old Richmond. Cribb would become Britain’s reigning boxing champion from 1809 to 1822 and one of his bouts even lasted an astounding 76 rounds.

Richmond would redeem himself in 1809 with the defeat of Maddox in 52 grueling rounds. He was 45 years old.

Eventually, Richmond won enough money to own his own pub, the Horse and Dolphin. It was here that he met Tom Molineaux, a fellow freed American slave. The two men instantly had a connection. Rather than keep fighting himself, Richmond trained Molineaux. Their goal was to defeat Cribb, who was then a national champion.

When Molineaux lost twice to Cribb, he fired Richmond as his trainer. Richmond lost tons of money on training his protege, and he had to sell his pub. Undaunted by the setback, Richmond became friends with Cribb, and the two formed a lasting friendship. Richmond frequented Cribb’s pub, the Union Arms in Westminster. This would be where he was last seen before his death in 1829.

Wikimedia Commons Tom Cribb pub in central London.

Richmond’s overall professional record was 17 wins and two losses. He would be 50 when he last stepped into the ring — and won.

“Impetuous men must not fight Richmond,” a prizefighting journalist wrote of Richmond, “as in his hands they become victims to their own temerity…The older he grows, the better pugilist he proves himself…He is an extraordinary man.”

High Society

In his later years, Richmond would go on to give boxing lessons and start a pugilism club in London. The pinnacle of Richmond’s success came in July of 1821. He and a group of pugilists were invited to the coronation of King George IV. At age 57, the 5’9″ Richmond was in top physical form. He was lean, powerful, and commanded the attention of people in the room.

Richmond was also the only black person in attendance. His attendance at the coronation showed a vast difference between whites and blacks in his time. Whereas whites came from privilege, pugilists often fought hard, usually on the streets, to get where they were. Indeed, as pugilists were seen as the ideal of English manhood, they were seen as the physical embodiment of success.

And Richmond’s place in the coronation was a comment on how blacks needed physical prowess, not intelligence, to get ahead in the 1800s. It was a stereotype that would persist for 150 years.

Twitter The memorial plaque for Bill Richmond inside the Tom Cribbs pub, 2015.

Even after earning the respect of England as one of the top pugilists in his day, Richmond was a one-of-a-kind specimen. After the coronation, it was back to spending time with Cribb and his career as a trainer or cabinetmaker. Eight years later, in December 1829, Richmond spent one final night in Cribb’s pub. He died the next morning at age 66, having grown up from a slave boy to a freed man with a wife and children.

At the Tom Cribb pub in central London, a plaque commemorates Richmond’s life. It reads, “freed slave, boxer, entrepreneur.”

But it seems in 200 years later, the story of Bill Richmond continues to unfold. Buried in a graveyard next to St. James church in London, Richmond’s final resting place may be recovered in a railway project which began in 2018. If his remains are found, DNA evidence could reveal much more about how he lived, how he died, and where his legacy continues today.

To his enduring fans, like his biographer, Richmond “was the pioneer of black sporting endeavor. He was the first black sportsman to achieve celebrity. There had been no one before him who had reached that level of national prominence.”

Indeed, perhaps without the likes of Bill Richmond fighting for his people’s place in history, other athletic giants like Muhammad Ali and Jesse Owens could not have been possible. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1999.

After this look at the boxer who fought to freedom, Bill Richmond, check out Yasuke, a freed African slave who became history’s first black samurai. Then, take a look at Mary Bowser, a former slave who helped bring down the Confederacy.