After more than a century of defying classification, this eel-like creature was finally placed in the evolutionary tree of life — potentially as the earliest-known ancestor of humankind.

When the fossilized remains of a tiny, eel-like creature were first discovered in Caithness, Scotland in 1890, scientists didn’t know what to make of them. They clearly belonged to some sort of prehistoric fish, but where exactly it sat in the evolutionary tree of vertebrates remained unclear for more than a century — until now.

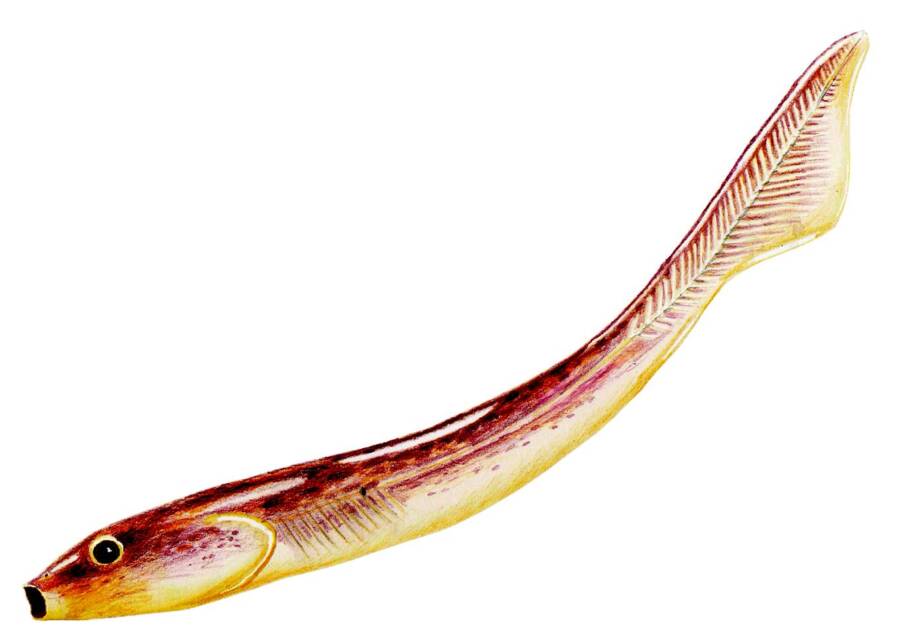

Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering ResearchPalaeospondylus gunni lived between 398 and 385 million years ago.

According to The Times, researchers have now determined the ancient creature was likely one of the first ancestors of four-limbed animals and human beings. As published in the Nature journal, the study identified the fish as one of the missing links in vertebrate evolution, shedding invaluable light on our prehistoric past.

Only with help from the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research in Japan were researchers able to generate micro-CT scans of the fish. According to Daily Mail, advanced synchrotron machines showed the critter was a limbless tetrapod with a jaw. For lead author Tatsuya Hirasawa, however, many questions remain.

“[It] possessed an excessively small lower jaw relative to the skull and the mouth opening was retracted,” he said. “Whether these features were evolutionarily lost or whether normal development froze half-way in fossils might never be known. Nevertheless, this evolution might have facilitated the development of new features like limbs.”

According to Live Science, the fossil was first found in Scotland at the turn of the last century. Researchers learned a lot in decades to come. Its eel-like body, for instance, was 2.4 inches long. It had a flat head and navigated the bottoms of deep, freshwater lakes feeding on leaves and organic debris.

Formally named Palaeospondylus gunni, the animal thrived in fairly hot and arid temperatures 390 million years ago. Hirasawa explained that it defied classification for 130 years because his predecessors lacked the tools to properly study the creature’s skeleton.

The fossilized remains had been so compressed by earth that the bones were practically mushed into an unrecognizable clump. Any discernible features only caused more confusion. It lacked limbs and teeth, which was unusual for vertebrates of the Devonian Period between 398 and 385 million years ago.

Numerous inaccurate conclusions regarding the animal’s place on the evolutionary tree were made as a result. A 2004 study designated the creature as a primitive lungfish, while Hirasawa himself labeled the animal a hagfish relative in 2016.

“This strange animal has baffled scientists since its discovery in 1890 as a puzzle that’s been impossible to solve,” said co-author Yu Zhi Hu from the Department of Material Physics at the Australian National University in Canberra.

Researchers from that very institution even concluded in 2017 that the animal was a cartilaginous fish, like modern sharks. Only technological advances in recent years would provide the scientific community with definitive answers. Hu and Hirasawa used micro-computed CT scans to create the clearest imagery of this species to date.

They found its inner ear was made of several semicircular canals like those of modern-day birds, fish, and mammals. This firmly distanced the species from hagfish, which don’t exhibit such qualities. They also found skull features identifying the animal as a tetrapodomorph, a group that includes all four-limbed creatures.

Wikimedia CommonsAn artistic rendering of what Palaeospondylus gunni may have looked like.

“Our analyses provided an inference that Palaeospondylus was a close kin to vertebrates having limbs (with fingers) and those having limb-like fingers,” explained Hirasawa.

This suggested the species was an aquatic predecessor of the very first marine animals to crawl ashore.

Ultimately, however, the species continues to be a well of prehistoric mystery. Why this tetrapodomorph lacked teeth, for instance, remains unclear. While Hirasawa posited these features were evolutionarily lost on the species or that the specimen in question was underdeveloped, only further research will reveal the truth.

“The strange morphology of Palaeospondylus, which is comparable to that of tetrapod larvae, is very interesting from a developmental genetic point of view,” he said.

“Taking this into consideration, we will continue to study the developmental genetics that brought about this and other morphological changes that occurred at the water-to-land transition in vertebrate history.”

After reading about the toothless eel that is potentially humans’ earliest known ancestor, learn about our tiny ancestor that’s essentially an anus-less mouth. Then, read about the 3.7-million-year-old footprints that belong to an unknown human ancestor.