On the final day of the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, Robert E. Lee ordered 12,500 Confederate troops to rush into the center of the Union Army's front lines — and within an hour, 1,100 men were dead and 5,400 more were wounded or captured.

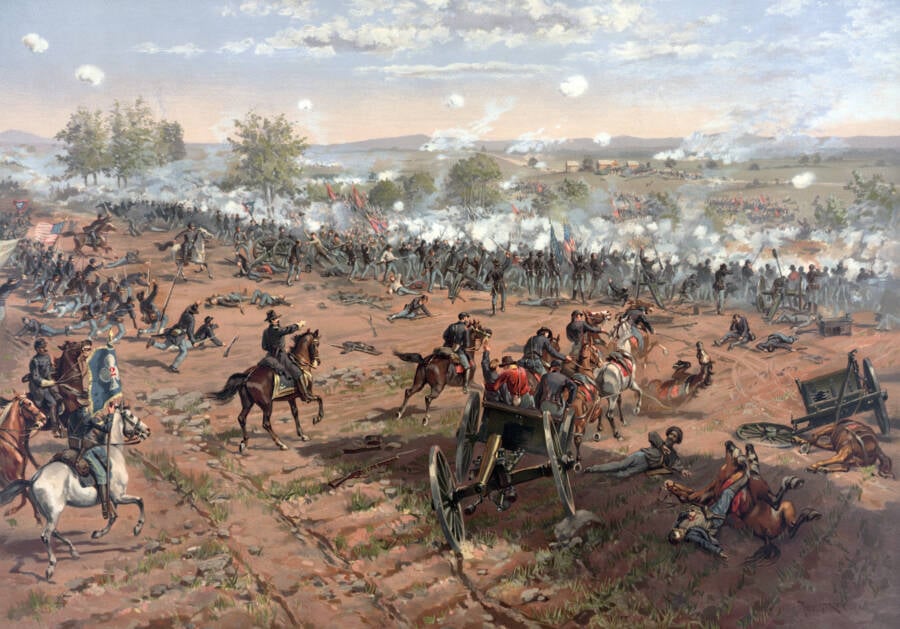

Science History Images / Alamy Stock PhotoA depiction of Pickett’s Charge, which took place on July 3, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg.

“Don’t forget today,” General George E. Pickett cried to his troops on July 3, 1863, “that you are from Old Virginia!” With that, three brigades of 5,400 Confederate soldiers from Virginia poured across a field in Gettysburg — a doomed assault that would become known as Pickett’s Charge.

The attack, which took place on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg, one of the most pivotal battles of the American Civil War, would go down in history. However, many facts about the assault have been obscured by time and the “Lost Cause” myth. The Confederates that day were not led by Pickett, for example, and his Virginians made up less than half of the attacking force.

Still, Pickett’s Charge remains a crucial moment from the Battle of Gettysburg, which would prove to be a turning point in the Civil War. Here’s everything you need to know about the ill-fated Confederate assault, from its formation to its outcome to who should be blamed for its failure.

How The Battle Of Gettysburg Broke Out Near A Tiny Crossroads

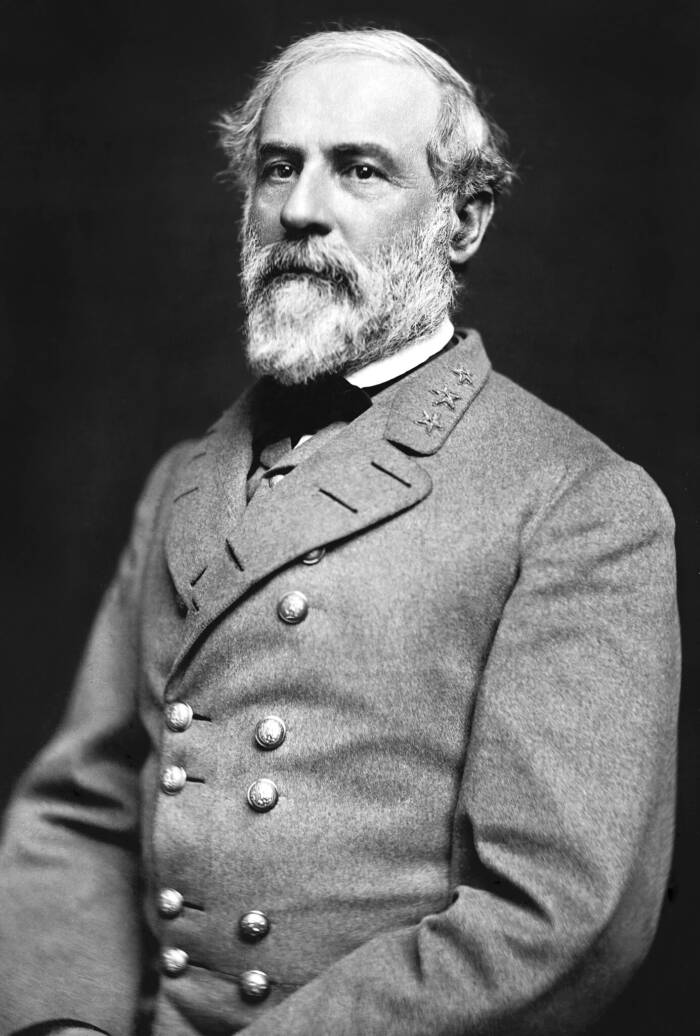

In the summer of 1863, the tides of the Civil War seemed to be on the side of the Confederates. After crushing Major General Joseph Hooker at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia that June, Confederate General Robert E. Lee directed his 75,000 men of the Army of Northern Virginia to march farther north.

They would, Lee hoped, smash through Union lines, threaten prominent cities like Washington D.C., and, perhaps, bring an end to the war.

Public DomainRobert E. Lee had already invaded the North once and hoped that a second invasion could prove decisive for the South.

But on July 1, Confederate troops led by Major General Henry Heth unexpectedly clashed with Union cavalry troops led by Brigadier General John Buford at the tiny crossroads town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The skirmish quickly developed into the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. By the afternoon, tens of thousands of troops were fighting under the hot July sun, and 30,000 Confederate soldiers were eventually able to triumph over 20,000 Union men. Though the Union forces were forced to retreat, they surged back on July 2 and continued the battle for another bloody day.

Alexander Gardner/Library of CongressConfederate soldiers lie dead in a part of the Gettysburg battlefield known as “Devil’s Den.”

Fierce fighting on July 2, including the famous bayonet charge by Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine Infantry at Little Round Top, meant that neither side could yet claim victory at Gettysburg. The battle continued.

As July 3 dawned, Robert E. Lee had to choose his next move. He decided to focus his attack on the center of the Union line, a doomed assault that would become known as Pickett’s Charge.

Inside Pickett’s Charge, The Doomed Confederate Assault On Cemetery Ridge

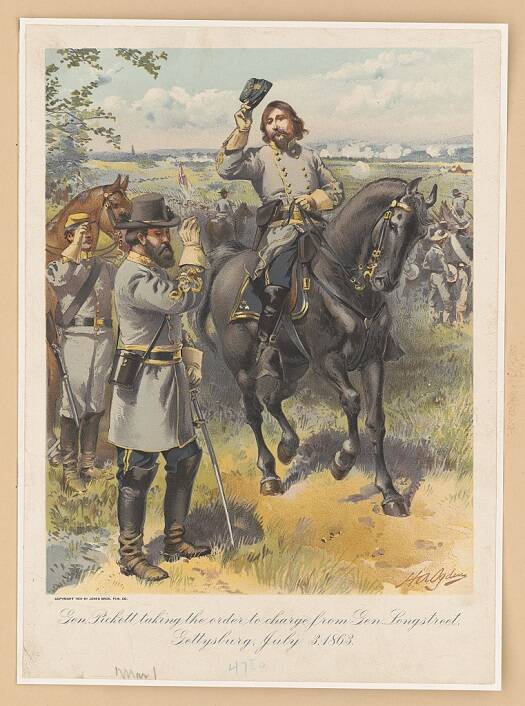

The execution of Lee’s plan fell to his trusted advisor, General James Longstreet. In fact, Pickett’s Charge is sometimes called Longstreet’s Assault. Though Longstreet disliked the strategy — he preferred striking the Union forces from the left and predicted hitting the Union center “would fail” — he prepared to follow Lee’s orders at around 3 p.m. on July 3.

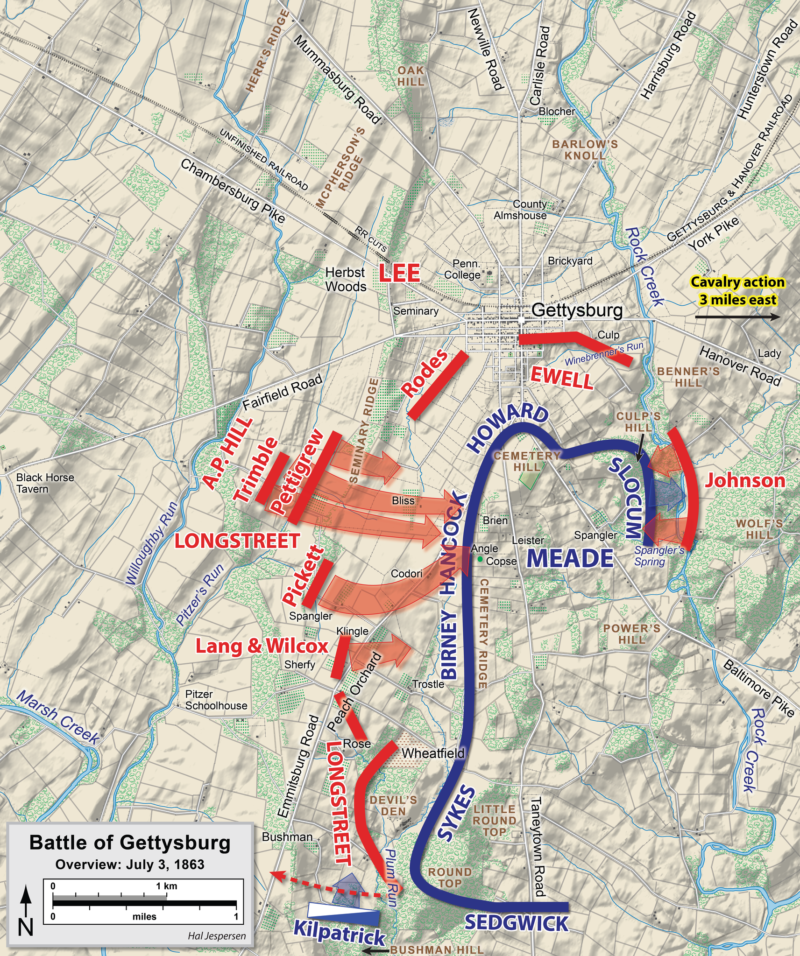

Under the command of Longstreet, three divisions numbering around 12,500 men and commanded by General Isaac Trimble, General James Johnston Pettigrew, and General George E. Pickett prepared for the assault. Pickett’s three brigades consisted of about 5,400 Virginians who had missed the first two days of fighting and were thus fresh and ready for battle.

Library of CongressA depiction of General Pickett taking his orders from General Longstreet, who’d grimly told his artillery chief that he believed Lee’s plan “will fail.”

As they marched toward the Union lines at Cemetery Ridge, Pickett famously cried to his men: “Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!”

With that, the Confederate soldiers began their assault. To those on the Union side, “Pickett’s Charge” initially looked invincible.

“None on that crest now need be told that the enemy is advancing,” Union officer Franklin Haskell later wrote to his brother. “Every eye could see his legions, an overwhelming resistless tide of an ocean of armed men sweeping upon us! …Right on they move, as with one soul, in perfect order, without impediment of ditch, or wall or stream, over ridge and slope, through orchard and meadow, and cornfield, magnificent, grim, irresistible.”

However, the Union troops at Cemetery Ridge weren’t going down without a fight. They rained down musket balls and cannon balls just as the approaching Confederates were stymied by fences and hills. Suddenly, the tides of the battle seemed to shift as the Confederates faltered.

“They were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust,” Union soldier Franklin Sawyer later recalled. “Arms, heads, blankets, guns and knapsacks were thrown and tossed in to the clear air… A moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle…”

As some brigades stalled or fell back, one of Pickett’s — led by General Lewis Armistead — approached a low stone wall at Cemetery Ridge known as the “Angle.” Armistead believed he saw a break in the Union lines and ordered his men to take it. “Come forward, Virginians!” he cried. “Come on, boys, we must give them the cold steel! Who will follow me?”

They poured across the wall — according to the American Battlefield Trust Armistead’s was the only Confederate brigade to reach the top of the ridge — but were quickly repelled by Union troops.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW/Wikimedia CommonsA map of Pickett’s Charge showing Pickett’s men at the center where they attempted to breach Cemetery Ridge.

Armistead was mortally wounded. His men were decimated. And the assault that came to be known as Pickett’s Charge quickly fell apart.

Overall, the Confederates suffered 6,555 casualties in an hour. Many of them were Pickett’s: His division had a casualty rate of 42 percent or about 2,655 men. When he was asked to consolidate his soldiers, Pickett — who some recall weeping — purportedly replied: “I have no division.”

The next day, Lee withdrew his troops, and the Battle of Gettysburg ended with a stunning Union victory. It proved to be a pivotal battle and the first in a series of important Union victories. In April 1865, Lee would surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in Appomattox, Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War for good after four years of fighting.

But Pickett’s Charge would soon take on a life of its own.

Pickett’s Charge As The ‘High-Water Mark’ Of The Confederacy

The courage and tragedy of Pickett’s Charge was not lost on its contemporaries. Even Lee is said to have remarked: “I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett’s division of Virginians did today in that grand charge.” But it soon took on a greater emotional significance.

After the war, Armistead’s foray over the wall was dubbed the “High-Water Mark” of the Confederacy and came to be acknowledged as the closest that Confederate troops had come to victory. And Pickett, who had actually only commanded about half of the men that day, became the face of “Pickett’s Charge.”

Public DomainGeneral George E. Pickett lent his name to Pickett’s Charge even though General James Longstreet was in command of the assault.

Though he had served under Longstreet, Pickett was recast in a central and romantic role. This is perhaps thanks to his wife, LaSalle Corbell Pickett. After Pickett’s death in 1875, she spent the rest of her life pushing the story of her husband’s “grand charge.” Before long, it became an important part of the “Lost Cause” narrative, which directed blame for the war away from the South and painted Confederate troops as heroic — not rebellious.

That said, Pickett’s Charge remains a contested moment for many. Why did it fail? Was it Lee’s fault? Did divisions from certain states fail to pull their weight, as other states alleged after the defeat at Gettysburg? Though he was purportedly distraught in the aftermath, Pickett offered a measured answer when he was later asked why his famous charge had failed.

“I always thought,” he said, “the Yankees had something to do with it.”

After reading about Pickett’s Charge, look through these Civil War photos taken by Mathew Brady, one of the first photographers to document conflict on film. Or, go inside the surprisingly complicated question of how many people died in the Civil War.