Ancient Roman graffiti in Pompeii has been found on walls throughout the city, nearly perfectly preserved since the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

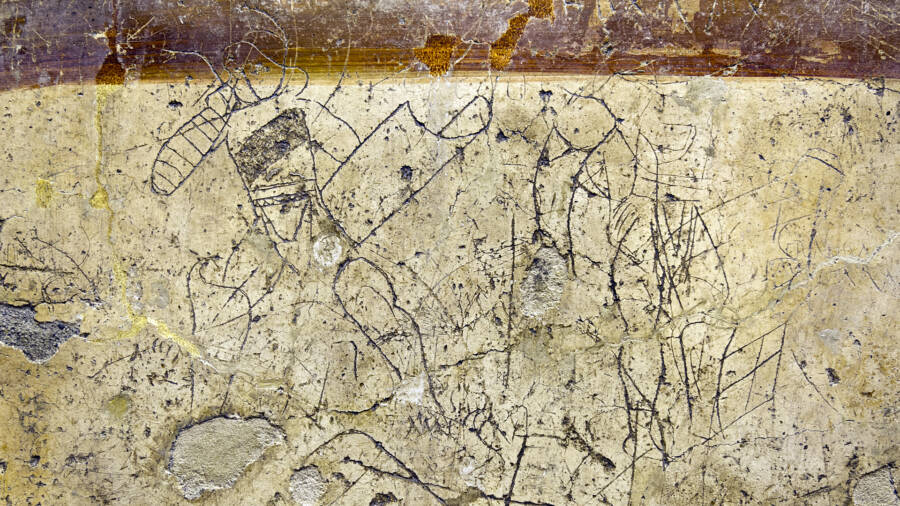

Darren Puttock/FlickrPompeii graffiti depicting a gladiatorial bout, housed at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D., most of Pompeii’s 12,000 inhabitants managed to escape, but the nearly 2,000 who remained instantly died of the heat and gas that devastated the town. But the ash that buried Pompeii also preserved the remains of a once-vibrant city, including a remarkable trove of Pompeii graffiti.

Though over 90 percent of the humorous, banal, and occasionally cruel words have faded over time, fortuitous cataloging from the 1800s and modern excavations have left scholars with much to study about the daily life and personal politics of the empire’s subjects as scrawled on public walls.

Ancient Roman graffiti in Pompeii runs a relatable gamut, from flattering portrayals of the city’s prostitutes to insults aimed at foes, from praise for friends or political figures to the simplest declarations saying “I was here.”

And historians continue to uncover Pompeii graffiti to this day, with one recent find even suggesting the accepted date of Vesuvius’ eruption is off by about two months.

A Precarious Existence At The Base Of A Volcano

Wikimedia CommonsMount Vesuvius overlooking the ruins of Pompeii.

Pompeii was first settled around 600 B.C. It maintained a status of semi-independence from various ruling states over the course of its existence, making it one of the most diverse towns in the Roman Empire by the first century — a prime place for public graffiti, anonymous or not.

Built to take advantage of the verdant and rich volcanic soil on the southern slope of Vesuvius, disaster was never far away. And in fact, Pompeii was still recovering from a devastating earthquake that nearly razed the city in 62 A.D. when Vesuvius erupted 17 years later.

According to Pliny the Younger, a Roman author who recorded the destruction in a letter he sent friend and historian Tacitus 25 years later, Mount Vesuvius erupted on the sixth day before September in 79 A.D.

Pompeii itself was only rediscovered by builders constructing a palace for the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon, in the 1700s. In the centuries since, archaeologists have found ancient Roman graffiti unlike any other.

Graffiti In Pompeii Was Everywhere

Darren Puttock/FlickrThis particular graffiti bears a style typical for political campaigns of the time.

The Roman graffiti in Pompeii is as varied as any found in modern cities. The oldest known scrawl was a humble yet determined demand to be acknowledged: “Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here.” The reason researchers know it is the oldest is that Gaius helpfully included a date when he was there, equating to Oct. 3, 78 B.C.

Many individual pieces of Pompeii graffiti are endearing declarations of well wishes, like one resident who found a wall on which to write, “Health to you, Victoria, and wherever you are may you sneeze sweetly.”

Some graffiti provides insights into how Romans thought about and treated death, less as a conclusion and more of a farewell: “Pyrrhus to his chum Chias: I’m sorry to hear you are dead, and so, goodbye!”

Not all of it is so kind, however. “Sanius to Cornelius: Go hang yourself!” reads one man’s challenge to another.

Jamie Heath/FlickrProtected graffiti in the Regio III neighborhood of Pompeii.

Nor, is all of it so wholesome. Perhaps most revealing is the Pompeii graffiti at its ancient two-story brothel.

Excavated in 1862, the brothel is known primarily by it’s well-preserved frescos detailing various offerings available. But more revealing is what is written in the walls of the individual rooms.

One woman claimed her status as “Murtis Felatris,” or Murtis, Queen Felator. Using a masculine verb for what ancient Romans considered a feminine act, Murtis subversively, and subtly, rewrote her role in Pompeii society.

“It recreates the life of the town,” said Washington University professor Rebecca Benefiel.

“It’s the voices of the people who were standing there, and thinking this, and writing it. That’s why the graffiti are just so special and so enthralling.”

Analyzing The Roman Graffiti Of Pompeii

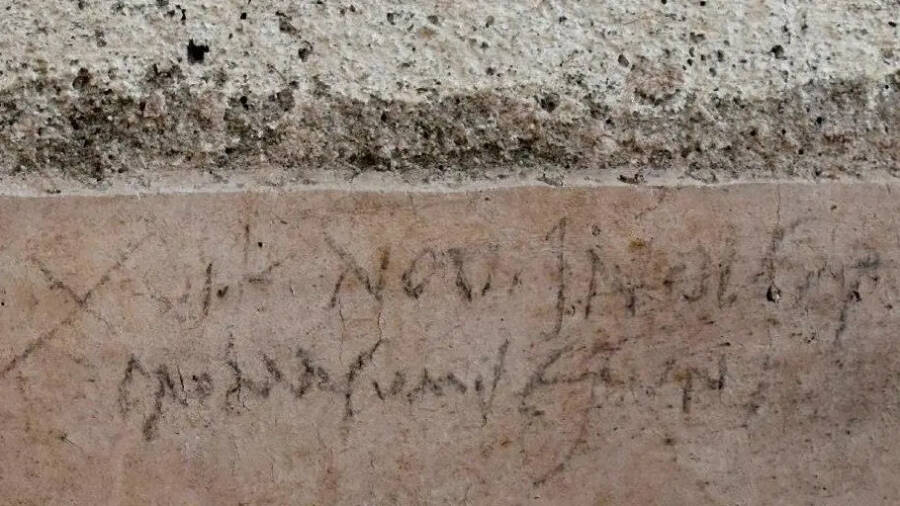

Archaeological Park of PompeiiThis charcoal inscription suggests that Vesuvius erupted two months later than historians have assumed.

In 2018, excavations in Pompeii’s Regio V area revealed a charcoal inscription that baffled experts. The writer dated it “XVI K Nov,” the 16th day before November, two months after Pliny the Younger said Mount Vesuvius covered the town in 19 feet of debris.

“The inscription appears in a room of the house which was undergoing refurbishment, while the rest of the rooms had already been completed; works must, therefore, have been ongoing at the time of the eruption,” the researchers wrote.

Thus, more than revealing intimate details about the lives led by residents of the Roman Empire’s most famed ruined city, Pompeii graffiti may also literally rewrite the historical timeline as experts have known it.

But, for those who visit Pompeii today, most of the graffiti visible to the public is encased behind glass, disabusing anyone from adding to the city’s legacy of wall writing. Though even if it can’t be touched, it is still as clear as though it was written yesterday by an idle hand — a declaration: I was here.

After learning about the Pompeii graffiti, take a look at the bodies of Pompeii. Then, learn about the military horse prepped to rescue victims found in Pompeii.