Project Iceworm envisioned a sprawling underground city in Greenland where the U.S. could house 600 nuclear missiles, but the project was shut down after less than a decade.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Project Iceworm planned to put as many as 600 nuclear missiles beneath Greenland.

For four short years after developing the first atomic bomb in 1945, the United States was the sole nuclear power in the world. But in 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic weapon, rocketing the Cold War into a new era. As the two nuclear powers scrambled for an edge, the Americans began to develop a top-secret project to hide nuclear weapons in the Arctic where they could easily strike at the Soviets. They named it Project Iceworm.

But Greenland’s ice sheet proved more powerful than the Cold War.

The Idea For Launching Project Iceworm

U.S. ArmyA massive construction project brought tons of supplies to the remote site of Project Iceworm.

By the 1950s, the Cold War had begun to gain steam, as both the United States and the Soviet Union had nuclear weapons. But storing nuclear missiles in the United States came with significant risks, as those locations could be attacked. So, at the end of the decade, the U.S. Army came up with a plan to build a secret nuclear missile facility in Greenland.

A 1951 agreement between the United States and Denmark allowed the Americans to build air bases in Greenland, an autonomous Danish territory. But the Americans wanted to go further. The U.S. Army wanted to build an underground nuclear facility where missiles could be stored.

The ambitious secret project dubbed Project Iceworm called for 52,000 square miles of tunnels under the ice – around three times the size of Denmark. Trenches positioned four miles apart would hold 600 mobile missiles which could be moved around the facility. And 11,000 soldiers would live beneath the ice, ready to strike when needed.

According to a 1960 top-secret document from the U.S. Army Engineer Studies Center, Greenland was the perfect site for nuclear weapons. It was just 3,000 miles from Moscow, putting missiles in easy striking distance of U.S. targets. The missiles of Project Iceworm would be underground, and easily moved, to avoid detection. And the site guaranteed second-strike capabilities if the Soviet Union fired nukes at the United States first.

National ArchivesThe construction of the nuclear facility ordered under the auspice of Project Iceworm.

“The missile force is hidden and elusive,” the report, recorded by the Atomic Heritage Foundation, stated. “It is deployed into an extensive cut‐and‐cover tunnel network in which men and missiles are protected from weather and, to a degree, from enemy attack. The deployment is invulnerable to all but massive attacks and even then most of the force can be launched. Concealment and variability of the deployment pattern are exploited to prevent the enemy from targeting the critical elements of the force.”

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the U.S. floated the idea of the facility to Denmark in 1958. When the Danish were noncommittal in their response, the Americans decided to move forward with Project Iceworm.

But Project Iceworm only worked if no one suspected the hidden ballistic missiles. So the Army invented a cover story.

Camp Century, The Nuclear ‘City Under The Ice’

In 1958, construction began at “Camp Century,” a “scientific research site” run by the Americans. But the “scientific site” was a cover for the sprawling underground nuclear facility built under Project Iceworm.

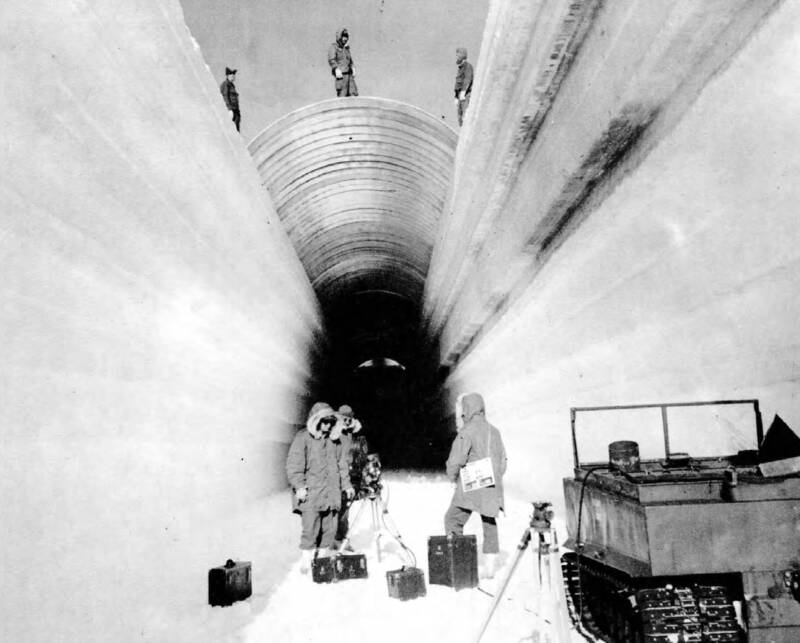

ERDC Cold Regions Research and Engineering LaboratoryThe construction of Project Iceworm.

Building Camp Century posed challenges from the beginning. First, engineers had to build a road through the ice. Then, they had to transport thousands of tons of supplies via bobsleds, which could only move at two miles per hour. That meant that the trip from Thule Air Base took 70 hours.

Next, engineers had to dig trenches into the snow and the ice, cover them with a roof of steel arches, and top them anew with snow. From there, they created a network of underground buildings. The longest trench became known as “Main Street,” and it was 1,000 feet long.

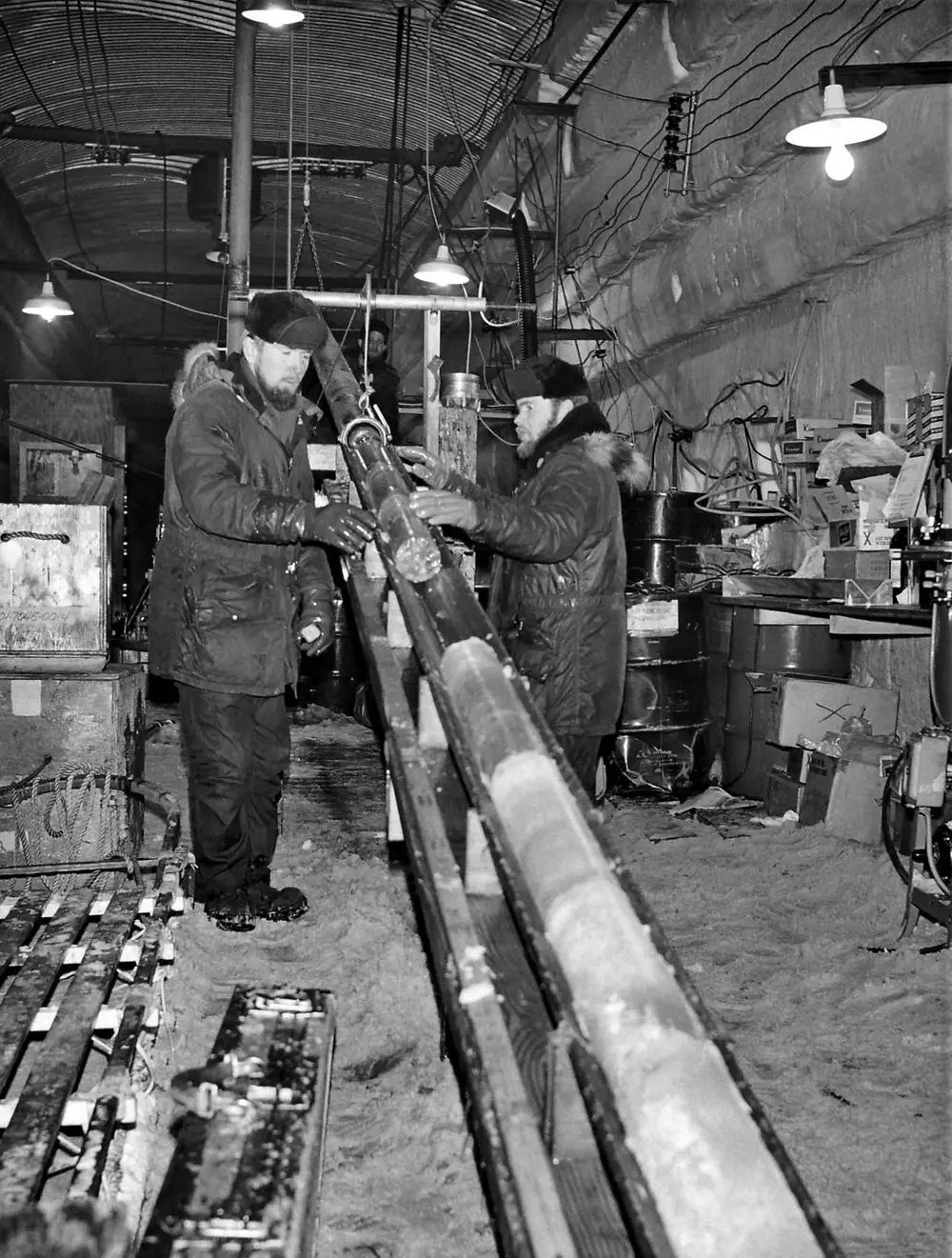

Eventually, the engineers built 26 tunnels which stretched across two miles, and led to dorms, a cafeteria, a hospital, and a rec hall. Eventually, the nuclear city would also have a hospital, a school, and a movie theater. Starting in 1960, a nuclear reactor powered Camp Century, and engineers planned to install two more reactors to keep things running.

In order to maintain the cover story, the Army even released a documentary on the “City Under the Ice” to show they had nothing to hide.

But they did have something to hide. Camp Century, under Project Iceworm, was built to hold enough medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) to destroy 80 percent of targets in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

It would have been a formidable nuclear site — if it had ever been finished.

How Project Iceworm Ultimately Failed

Project Iceworm quickly ran into major problems. For one, the operation required 52,000 miles of tunnels. But only two miles were ever constructed – and the tunnels kept collapsing under the pressure of the Greenland ice sheet. What’s more, the engineers planned to run the city on nuclear power. But frigid temperatures could crack metal, increasing the risk of accidents.

US ArmySteel archways covered the underground tunnels that hid Camp Century. As snow fell, the camp became more deeply embedded in the ice.

Beyond the challenges of building Camp Century were the challenges of operating it. The environment in Greenland was harsh on the best days: Temperatures could hit -70°F and winds whipped by at 120 miles per hour.

Ultimately, Camp Century proved to be more trouble than it was worth. The facility’s single nuclear reactor only functioned for 33 months, and the nuclear city, meant to house 11,000, never had more than 200 inhabitants.

US Army/National ArchivesThough Project Iceworm envisioned a facility with 52,000 square miles of tunnels, only two miles were ever built.

The military canceled Project Iceworm in 1963, though the public didn’t learn the truth about Camp Century until the 1990s. But the top secret military project would have long lasting implications for the entire world.

Cold War Waste Beneath The Ice

After ending Project Iceworm, Camp Century continued to operate on a limited basis until 1966. With an annual snowfall of four feet, however, the abandoned nuclear city was increasingly buried under snow and ice. Its tunnels eventually collapsed, and the U.S. Army moved out for good.

But they left tons of hazardous waste behind.

US ArmyRadioactive waste hidden beneath Greenland’s ice will begin emerging by 2090.

The Army thought that the snow would bury the radioactive coolant, diesel fuel, and wastewater. A 2016 study, however showed that they were wrong.

Camp Century waste stretches the size of 100 football fields. And Arctic warming will expose the waste by the end of the century.

“They thought it would never be exposed,” climate scientist William Colgan told The Guardian in 2016. “Back then, in the 60s, the term global warming had not even been coined. But the climate is changing, and the question now is whether what’s down there is going to stay down there.”

After learning about Project Iceworm, read about Project A119, the U.S. Air Force plan to detonate a nuclear bomb on the moon. Then, discover the harrowing story of the Runit Dome, the concrete “tomb” of nuclear waste in the Marshall Islands — that’s started to crack.