The Pullman Strike of 1894 saw more than 250,000 railroad workers walk off the job and halt the U.S. economy for months — until federal troops were called in.

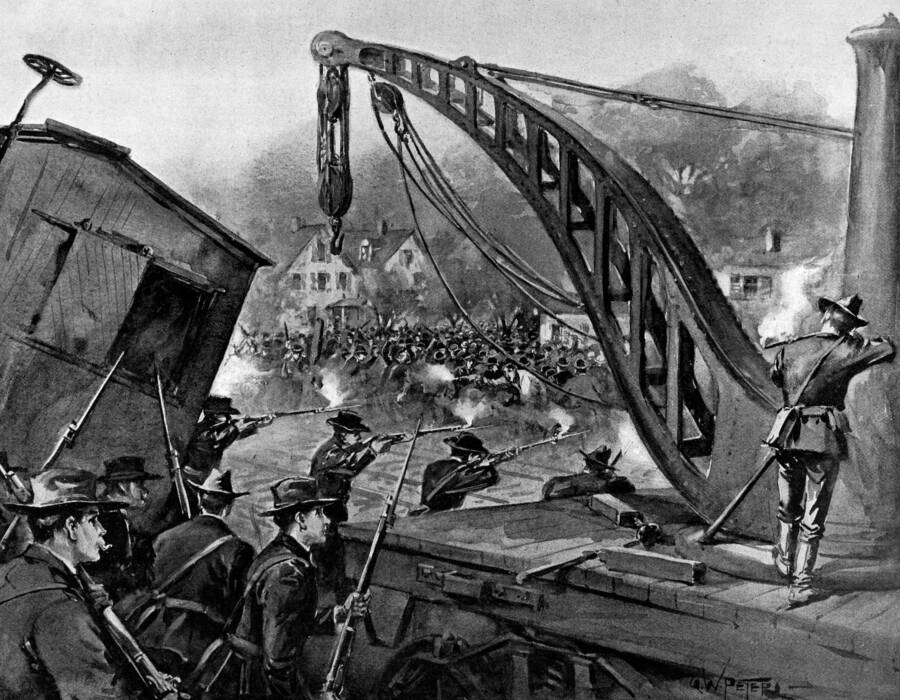

Harper’s Weekly/Public DomainNational guardsmen open fire on striking railroad workers on July 7, 1894.

In 1894, the Pullman strike saw hundreds of thousands of railroad workers walk out on the job. Angry with high rents in their company town owned by the Pullman Car Company and recent wage cuts, the striking workers boycotted any trains that used Pullman cars.

The Pullman strike, backed by the American Railways Union, effectively shut down the American railroad from May through July because the Pullman Company had a near-monopoly on sleeper cars west of Chicago. And it might have worked — had the federal government not stepped in.

Until early July 1894, the strike had been largely peaceful, if highly disruptive. Strikers blocked railroad crossings, uncoupled Pullman cars from trains, and occasionally clashed with strikebreakers, though the violence had been minimal.

But when 12,000 federal troops stormed the railyards, the bloody clash forced workers back on the job at poverty wages and left 70 workers dead across the United States. And although the deadly end to the Pullman strike initially served as a warning to labor organizers, it ultimately ushered in a new progressive era in American politics and led directly to the creation of the Labor Day holiday.

George Pullman And The Pullman Company Town

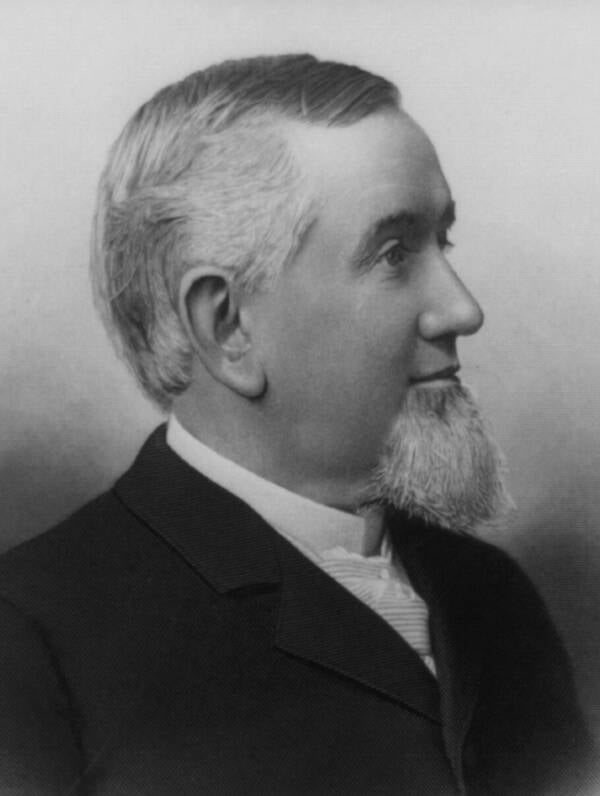

George Pullman entered the railroad industry at the right moment. From 1850 to 1860, railroad mileage tripled. Passengers traveling long distances would climb off the train each night and stay in a hotel before continuing their journey. Pullman stepped in to design a luxury sleeping car that eventually gave him a powerful monopoly.

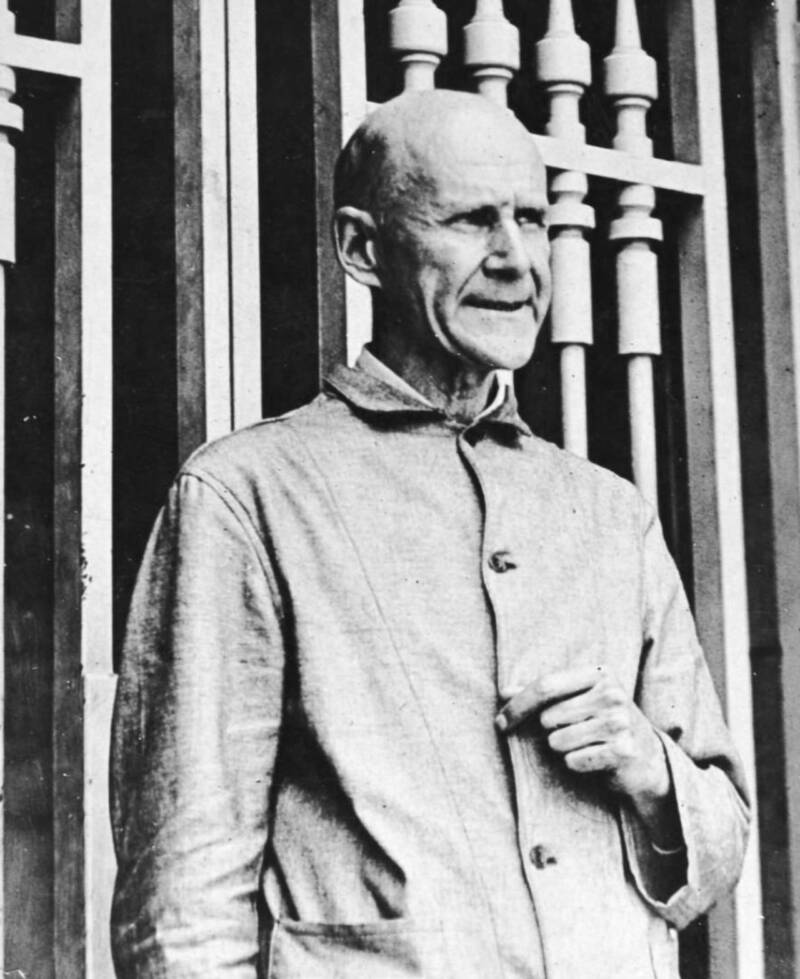

Library of CongressRailroad tycoon George Pullman, owner of the Pullman Company and Pullman, Illinois.

And Pullman wasn’t above pulling stunts to get ahead. After Lincoln’s assassination, Pullman pulled strings to get the president’s casket in one of his sleeping cars as a marketing ploy.

The tycoon also vowed to reform the troubling elements of society. In the 1880s, Pullman built a company town 12 miles south of the Chicago Loop that would cultivate moral principles in his workers. Named after himself, Pullman, Illinois, tightly controlled workers’ lives.

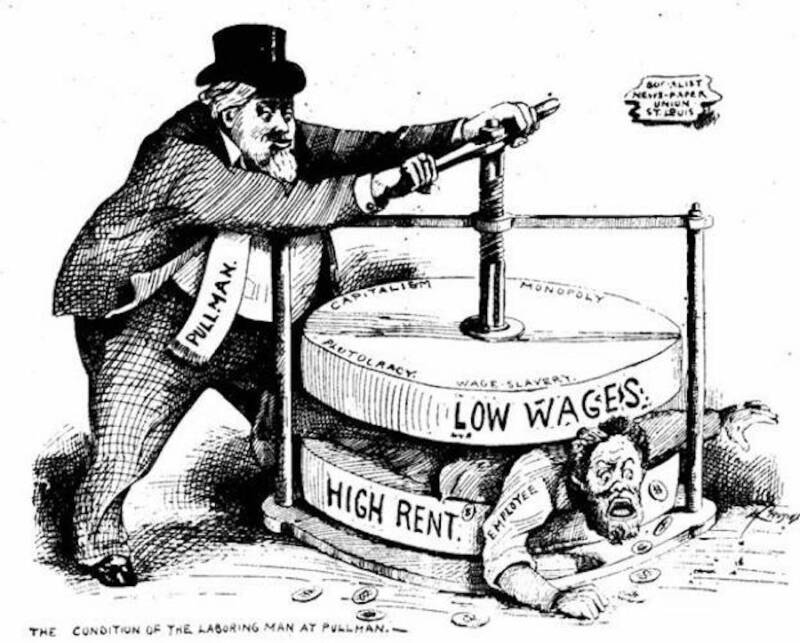

Workers could not own their homes, and Pullman employees paid a third of their income in rent directly to the company, deducted automatically from their paychecks. Company officials prowled the streets to ensure workers were following the draconian town rules, which included prohibitions on alcohol and public gatherings not sanctioned by the company.

One critic described Pullman as a “benevolent, well-wishing feudalism, which desires the happiness of the people, but in such way as shall please the authorities.”

Six years before the Pullman strike, The Chicago Tribune warned that the town of Pullman “may appear all glitter and glow, all gladness and glory to the casual visitor, but there is the deep, dark background of discontent which it would be idle to deny.”

The tension between the workers and the company grew in 1894 when Pullman cut wages while refusing to reduce his employees’ rents.

What Caused The Pullman Strike?

The panic of 1893 was the worst depression Americans had ever endured. George Pullman responded by firing workers and cutting wages for those who remained by about 30 percent. Rents in the company town, however, stayed the same. Pullman workers walked home with poverty wages after the company deducted their rent.

Chicago Labor Newspaper/Public DomainThe Chicago Labor Newspaper summed up the reasons for the strike in a cartoon depicting workers squeezed by low wages and high rent.

The workers grew desperate. They tried to negotiate with the company. But Pullman fired workers for daring to ask for more.

Thomas Heathcoate, a Pullman employee, lamented, “We do not know what the outcome will be, and in fact we do not care much. We do know that we are working for less wages than will maintain ourselves and families in the necessaries of life, and on that one proposition we absolutely refuse to work any longer.”

So on May 11, 1894, four thousand Pullman workers went on strike. The following month, the striking workers reached out to the American Railway Union for support. Leader Eugene V. Debs supported the strike.

Debs declared Pullman a “rich plunderer” who was “an oppressor of labor.”

“The paternalism of the Pullman is the same as the interest of a slaveholder in his human chattels,” Debs railed. “You are striking to avert slavery and degradation.”

Suddenly, a regional strike of a few thousand workers became a national strike of the 250,000 members of the American Railway Union. Rail traffic halted. Prices soared. Factories ran out of coal. And mines closed with no way to transport their goods.

How Did The Pullman Strike End?

The striking railroad workers boycotted any train with a Pullman car. Since Pullman had a monopoly on sleeper cars by the 1890s, that effectively shut down the country’s rail system.

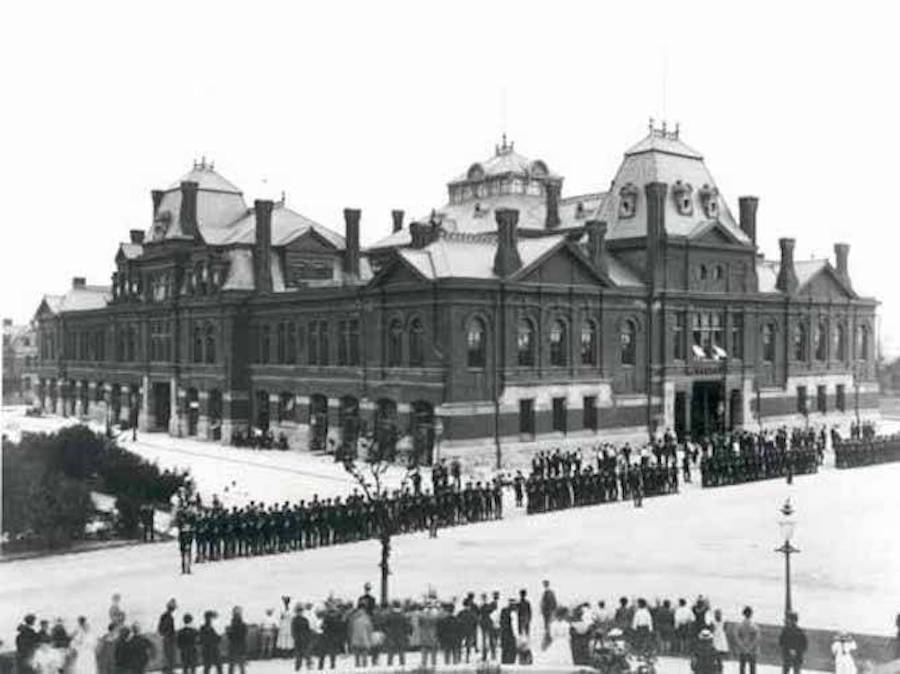

Northern Illinois University Digital LibraryStriking workers face off against the National Guard outside the Arcade Building in Pullman, Illinois.

In Chicago, the striking workers found a friend in Mayor John Hopkins, who considered George Pullman his enemy. The mayor helped raise money for the workers and ordered police not to interfere in the strike. Chicagoans showed their support by walking the streets wearing a white ribbon.

But the federal government had no sympathy for the Pullman strike. Attorney General Richard Olney, who once worked for the railroads, declared that the strike had pushed the country to “the ragged edge of anarchy.”

So the government turned to the Sherman Anti-Trust Law, designed to fight monopolies, and used the law against labor.

President Grover Cleveland sent 12,000 National Guard soldiers to Chicago to break the strike, which had been largely peaceful until federal troops arrived armed with bayonets. Strike leaders, including Debs, faced arrest. A rail yard burned to the ground. And dozens of civilians died.

Debs declared that federal troops shooting workers would trigger a civil war. Instead, it turned sentiment against the Pullman strike, with the workers now seen as rioters. Debs spent the next six months in jail and walked out convinced that socialism was the only way to protect workers.

The Impact of the Pullman Strike

Throughout the Pullman strike, George Pullman refused to even negotiate with the workers. His company had “nothing to arbitrate,” Pullman declared. And when federal troops broke the strike, Pullman’s workers had to return to their low-wage jobs with no concessions from the company.

Corporate monopolies, backed by the power of the state, had defeated labor.

Wikimedia CommonsEugene Debs returned to a federal penitentiary in 1920 for opposing World War I.

But George Pullman’s reputation never recovered. His fellow industrial capitalists scorned him as a “God-damned fool” for not negotiating with his workers. A federal commission declared Pullman policies “behind the age.” And a court forced the company to disband ownership of the town of Pullman, which was later annexed into Chicago.

The same month that President Cleveland sent troops to break the Pullman strike, he signed legislation to create the Labor Day holiday. The federal government publicly celebrated workers — while showing it would viciously stamp out any action that harmed corporate profits.

But although the Pullman strike itself failed, it led to a sea change in American labor. In the years following the Pullman strike, workers increasingly joined unions and fought for higher wages, better working conditions, and shorter working hours.

And when George Pullman died three years after the Pullman strike, his Chicago grave had to contain concrete reinforcements to prevent desecration. Eugene Debs eulogized Pullman by quipping, “He is on equality with toilers now.”

After learning about the bloody Pullman Strike, read about the newsboy strike of 1899. Then take a look at photos of radical movements in the early 20th century.