The newsboy strike of 1899 pitted poor newsies as young as seven against millionaire newspaper moguls William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer in a battle over fair wages.

Wikimedia CommonsYoung newsboys like this one made up the ranks of the newsboy strike of 1899.

Just before the turn of the 20th century, a powerful strike paralyzed newspaper distribution in New York City. But the strikers were not professionals, nor were most of them adults. The newsboy strike of 1899 was led by boys — newsies, who went head-to-head with newspaper moguls William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.

Angry at what Hearst and Pulitzer charged them for a newspaper bundle, the boys, some as young as seven, refused to sell their publishers’ papers. Instead, they marched, held rallies, and punished any “scabs” who dared to disobey. “Just stick together,” declared Kid Blink, one of the strike leaders, “and we’ll win.”

The newsboy strike of 1899 began in mid-July, and by August, the ragtag group of poor and homeless newsies had brought Hearst and Pulitzer to their knees. After initially dismissing the strike as trivial, the moguls agreed to come to the bargaining table.

Why The Newsboys Wanted To Strike

Newsboys (and sometimes girls) had long made up the fabric of booming metropolises like New York City. Darting between carts and hanging out on corners, they hawked the day’s paper for a penny. By the time of the newsboy strike of 1899, the number of newsboys had exploded, thanks to the recent introduction of evening editions, which people grabbed for their commute home.

Wikimedia CommonsNewsboys could often sell three times as many evening papers than morning papers.

For a long time, the newsboys had worked in relative peace with newspaper publishers like William Randolph Hearst, who published The New York Evening Journal and Joseph Pulitzer, who published The Evening World.

They had a system. The newsboy would buy a stack of 100 newspapers from the publisher for 50 cents, then sell them for one penny.

And although there had been brief newsies strikes before, they paled in comparison to what was about to happen.

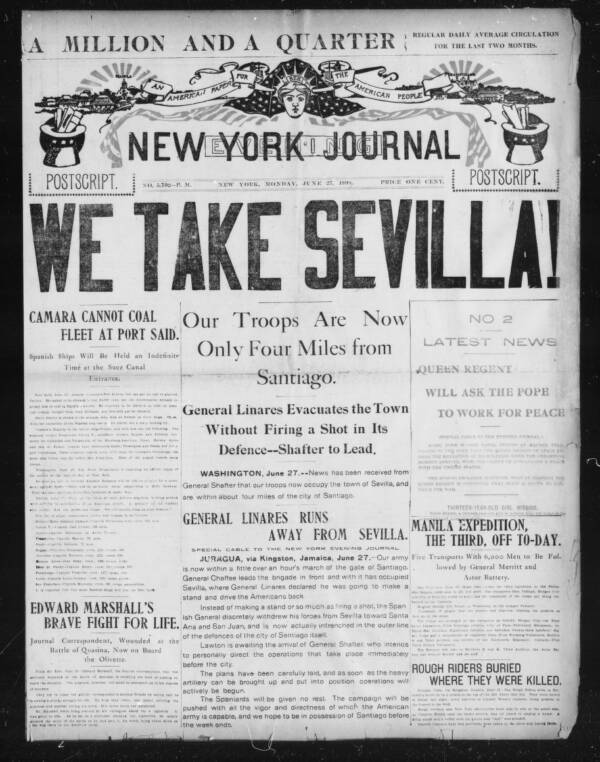

Everything started to shift when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898. Then, publishers started charging newsies 60 cents instead of 50 for their bundles. Although they didn’t know it at the time, this would form the basis of the newsboy strike of 1899 just a year later.

Newsies didn’t mind — not at first. The public had a massive appetite for war stories. And the papers — filled with grabby, exciting headlines — sold like never before.

Library of CongressAn attention-grabbing headline from the New York Evening Journal, 1898.

When the war ended, most publishers lowered their price back to 50 cents. But Hearst and Pulitzer kept charging the newsboys 60 cents for 100 papers. The moguls were competing with each other using flashy front pages and extra editions, and they wanted to save money where they could.

Before long, the newsboys started to feel the difference. Their frustration came to a head on July 18, when newsboys in Long Island City found out that a Journal delivery man had been selling them bundles with fewer than 100 papers.

The furious newsboys tipped over his wagon and stole his papers. Energized and encouraged, the newsboys decided to tackle a much bigger injustice: the price of their bundles.

On July 19, the newsboys gathered in Manhattan’s City Hall Park to form a union. They demanded that Hearst and Pulitzer reduce the price of newspaper bundles back to 50 cents. And the newsboys declared that they would not buy the World or the Journal until the moguls complied.

The newsboy strike of 1899 had begun.

The Fight Between Newsies And Moguls

At first, the newspaper moguls shrugged off the newsboys’ demands. Don Seitz, The New York World’s managing editor, sent a breezy memo to Pulitzer about the strike on July 21.

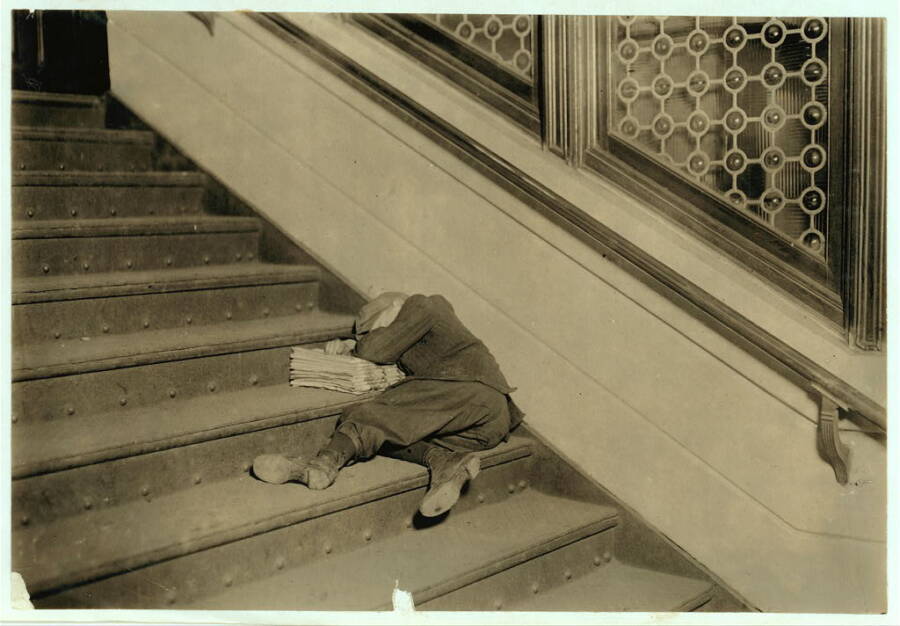

Library of CongressA young newsboy uses his papers as a pillow. New Jersey, circa 1912.

“Had some trouble to-day through the strike on the part of the newsboys,” Seitz wrote. But he assured his boss that the strike would be “sporadic” and that the situation was “well in hand.”

The newsboys, however, had no intention of backing down. On July 22, 100 newsies descended on ‘Newspaper Row’ — where the papers were distributed — and threatened The New York World and The New York Journal with clubs.

At first, the police were able to disperse the young strikers. But the newsboy strike of 1899 continued, and the newsies reconvened in even greater numbers around Columbus Circle. Five hundred of them shouted, threw fruit, and stole newspapers out of the wagons.

That day, Seitz sent a second memo. This one had a note of alarm crept into his voice. “The newsboys strike has grown into a menacing affair… It is proving a serious problem,” Seitz wrote. “Practically all the boys in New York and adjacent towns have quit selling.”

And by July 24, Seitz was in a panic. “The advertisers have abandoned the papers and the sale has been cut down fully 2/5,” he told Pulitzer. “It is really a very extraordinary demonstration.”

Over the next two weeks, the newsboys made themselves heard. They marched across the Brooklyn Bridge and flooded the streets of downtown Manhattan. Newsies tore up copies of the Journal and the World and tossed water on newsstand owners who didn’t support them.

Library of CongressYoung newsboys like these paralyzed New York City with rallies, marches, and impassioned speeches.

As the World’s circulation plummeted from 360,000 to 125,000, the newsies held a rally on July 25. Five thousand young newsies listened as their 18-year-old strike leader, Louis “Kid Blink” Baletti, stepped up to address the crowd.

Blink — so called because he wore an eyepatch — rallied the newsies with an impassioned speech.

“Ten cents in the dollar is as much to us as it is to Mr. Hearst the millionaire,” Blink declared. “Am I right? We can do more with ten cents than he can do with twenty-five. Is it boys?

“If they can’t spare it, how can we? I’m trying to figure how 10 cents on 100 papers can mean more to a millionaire than it does to newsboys, an’ I can’t see it!”

Before long, the newsboys were winning — at least on the public relations front.

“The people seem to be against us,” Seitz told Pulitzer on July 24. “They are encouraging the boys and tipping them…[and] they are refraining from buying the papers for fear of having them snatched from their hands.”

And within a mere two weeks, the newsboy strike of 1899 had done so much damage to Hearst and Pulitzer’s papers profits that the moguls agreed to talk.

The Legacy Of The Newsboy Strike Of 1899

On Aug. 2, 1899, the newsboys struck a deal with Hearst and Pulitzer. They would continue to buy bundles for 60 cents — however, both the World and the Journal would take back any unsold papers at a full refund. The boys agreed. They went right back to selling papers.

Library of CongressNewsies in Newark, New Jersey, 1909.

But although the strike lasted only two weeks, it left an outsized legacy on American life and culture. The newsboy strike of 1899 encouraged similar strikes in Hartford, Connecticut (1909), Butte, Montana (1914), and Louisville, Kentucky (in the 1920s).

Plus, the appeal of ragtag young newsboys fighting against millionaires like Hearst and Pulitzer has endured. In 1992, Disney released a popular film based on the strike called Newsies. Featuring a young Christian Bale — and a character named for Kid Blink, eyepatch and all — it dramatized the newsies strike against Pulitzer and Hearst.

The Disney film proved so popular that it was later adapted for Broadway. But the Disney version of the Newsboys Strike of 1899 does leave out some key details.

Namely, young newsies continued to struggle in poverty even after winning concessions from Hearst and Pulitzer. It took another twenty years for the United States to enact child labor laws. Until then, newsboys continued on much as they always had.

But for one, brief, glorious moment, the newsboys of New York City grabbed the world’s attention. They went head-to-head with some of the world’s richest and most powerful men. And, against all odds, this ragtag crowd roared to victory.

After reading about the newsboy strike of 1899, look through these shocking photos of child labor in New York at the turn of the century. Or, look through these facts about life in New York’s tenements.