The case of Dr. Sam Sheppard was so controversial from the outset that the federal court later ruled his initial trial a "mockery of justice."

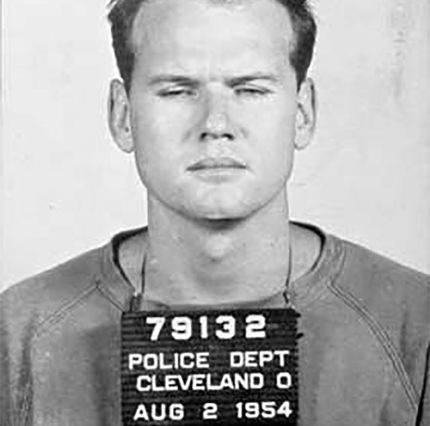

AlchetronDr. Samuel Sheppard’s mugshot.

In the early hours of July 4, 1954, the wife of a respected neurosurgeon was bludgeoned to death. The first person to find her body was her husband, Dr. Sam Sheppard, whose spotty alibi quickly made him the prime suspect in her murder.

A media blitz and public witch-hunt turned Sheppard into a grisly pariah. The court even called the case an absolute “carnival.” It would be another decade before Dr. Sheppard could earn his freedom, but not before his reputation, his family, and his character would be dredged through the mud.

The Murder Of Marilyn Sheppard

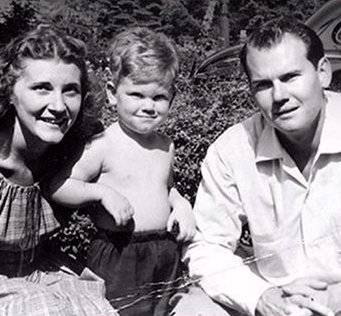

CSU digital archiveMarilyn, Sam “Chip” Jr., and Sam Sheppard.

The neurosurgeon lived with his wife, Marilyn Reese Sheppard, and seven-year-old son, Sam Reese “Chip” Sheppard, on a fashionable lakefront property in Bay Village, Ohio. On the night in question, the Sheppards had hosted neighbors for a movie and the neurosurgeon shortly afterward fell asleep on a daybed downstairs. His wife saw the neighbors out, put their son to bed, and went upstairs to sleep herself.

After an exhausting day at the emergency room, Sheppard was startled awake by the sound of his wife’s screams. He rushed upstairs to the bedroom to find a “white form” bent over his barely conscious wife. The next thing Sheppard knew, he too was unconscious.

Sometime later when Sheppard came to and heard the intruder downstairs. He confronted the intruder who was tall, about six feet, and with bushy hair. Sheppard chased the intruder outside and down to the beach where he was knocked unconscious again.

The next time he regained consciousness, he was shirtless and partially submerged in the lake. He returned to his house and checked on his seven-year-old son, who had miraculously slept through the whole commotion. He called Spencer Houk, his neighbor and the mayor of Bay Village at about 5:40 a.m.

The police were not notified until after the mayor arrived at the murder scene with his own wife.

Marilyn, aged 30 and pregnant, was on her bed, her face unrecognizable from the severe trauma to her head. Her pajama top was pulled up revealing her breasts, while her pajama bottoms had been pulled down to her ankles, with one completely removed from her leg.

CSU digital archiveThe crime scene: Marilyn Sheppard’s bloodied outline.

The first police officers arrived four minutes about the mayor. They initially assumed a robbery had gone wrong. Shortly after, Dr. Sheppard’s brother arrived and they went to the hospital together to see to his head injuries.

At 8 a.m., Cuyahoga County coroner, Sam Gerber, arrived at the crime scene and he thought it looked staged — especially because there appeared to be no signs of forced entry. No murder weapon was found though a trail of blood from the weapon was found going from the bedroom, downstairs, and then to the front porch as it was carried out of the house.

Outside in a bush, he found a canvas bag with Sheppard’s blood-stained wristwatch, fraternity ring, and key. Gerber surmised from this that a robbery had been staged to hide a domestic murder.

He figured Marilyn was killed sometime between three and four in the morning as her watch was stopped at 3:15 a.m. He did not appreciate that Dr. Sheppard was absent from the house while he did his investigation, and an hour later headed the hospital to interview the neurosurgeon.

Gerber felt that Sheppard’s encounter with the “bushy-haired intruder” and his head injuries sounded fabricated. Further, he sensed no remorse in Sheppard’s statement.

Sheppard refused to undergo questioning from police as the days passed, and claimed this was on his doctor’s orders. The problem was that his doctor was also his older brother, Stephen. This evasiveness spelled a precarious situation for Sheppard.

It was only going to get worse.

Sam Sheppard’s Trial By Media

CSU digital archiveSam Sheppard is questioned by coroner Sam Gerber.

By the end of the first day of the investigation, rumors of Sheppard’s infidelity hit the press alongside details of his wife’s murder.

Two weeks after Marilyn’s death, a front-page editorial in the Cleveland Press demanded a public inquest. Gerber responded to the demand and subpoenaed Sheppard and his family to attend an inquest held in a local high school that evening.

A media circus unfolded. The press watched on as Gerber presided over the inquest of Sam Sheppard as both judge and jury. For three evenings, witnesses were interrogated about Sheppard’s character and his marriage. Sheppard’s attorney, William Corrigan, was ordered to sit in the audience away from his client. At one point Corrigan protested to the jeering from the audience and Gerber had him promptly evicted from the hearing.

Sheppard was grilled about an alleged affair with a beautiful former lab technician named Susan Hayes. Sheppard denied the affair, but it was a lie that would later have serious consequences for the doctor.

A week after the inquest had finished, the Cleveland Press demanded that Sheppard be forced to admit to the crime. Yet again Gerber responded to the press and had Sheppard arrested and officially charged with his wife’s murder.

On Oct. 18, 1954, Sam Sheppard was put on trial. At the same time, the press amped up their coverage, perhaps in part because Louis Seltzer, the editor of the Cleveland Press, had his own personal stake in seeing the enviable young doctor defamed.

The presiding judge, 70-year-old Edward Blythin, was seeking re-election, and it is suggested that the judge allowed the press into the courtroom because Seltzer had the power to make or break his political career. Whether or not this was true, press from around the country were in attendance, including celebrity journalist Dorothy Kilgallen, who wrote about each day of the trial in her national column.

“A Carnival Atmosphere”

CSU digital archiveThe jury visits the crime scene.

The first day of the trial started with a press tour of Sheppard’s home to see the crime scene while Sheppard was hauled around in handcuffs. Back in the courtroom, the prosecution showed the jury a slideshow of grisly photographs of Marilyn’s autopsy. Sheppard was denied being excused from the court during this slideshow when he requested it.

Then, Sheppard’s guilt seemed certain when Sam Gerber confidently asserted that a supposed bloody outline on the victim’s bed was from a multi-pronged surgical instrument that only a doctor like Sheppard could have possibly acquired.

Though no murder weapon was ever even found, Sheppard’s attorney was denied access to the physical evidence, and therefore could not effectively cross-examine Gerber about his dubious evidence.

The prosecution’s final witness was Susan Hayes, the young lab technician whom Sheppard had denied having an affair with during Gerber’s inquest. To Sheppard’s dismay, Hayes said it was true. Under pressure, Sheppard broke down when he took the stand and also admitted to the affair.

In Sheppard’s defense, Corrigan produced three witnesses who testified to seeing the “bushy-haired” intruder Sheppard had described in the vicinity of the home around the time of the murder. The Bay Village police even made a sketch of the intruder from an eye-witness who drove past Sheppard’s home at 3:50 a.m.

Even so, after five days of deliberation, the jury found Sheppard guilty of second-degree murder. The jury did not believe the crime was premeditated, so Shepard was spared a first-degree murder charge, and therefore a death sentence.

Instead, he received life imprisonment with the possibility of parole in a decade.

The Case Rages On

Two weeks after the verdict, Sheppard’s mother committed suicide, followed by the death of his father from a hemorrhaging ulcer just one week later. Sheppard was allowed to attend the funeral in handcuffs. For the next seven years, Sheppard fought his ruling from a maximum security prison near Columbus.

Despite the toll his case had taken on the family, Sheppard’s two brothers rallied around him. They hired a forensic scientist, Dr. Paul Leeland Kirk, to review the State’s physical evidence. When Kirk examined the blood splatters on the walls, he found one part of the wall was devoid of blood. This, Kirk concluded, proved that the killer would have been covered in blood.

But Sheppard had only one large spot of blood on his trousers. Kirk also determined that some blood spots were from the backswing of the murder weapon, which showed clearly it had been wielded from a left-handed person. But Sheppard was right-handed.

Furthermore, broken pieces of Marilyn’s teeth were found underneath her body. Her teeth had been broken out, not in, which was evidence that Marilyn had bit her assailant. When Sheppard has been examined at the hospital, no bite marks or open wounds were discovered on his body.

But when Corrigan presented this new evidence to Judge Blythin for a retrial, the judge rejected the appeal. Corrigan took the matter all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court but was denied a retrial. When Corrigan died five years later, the chance of a retrial seemed unlikely. Sheppard’s best course of action appeared to take a lie detector test in the hope of reducing his life sentence.

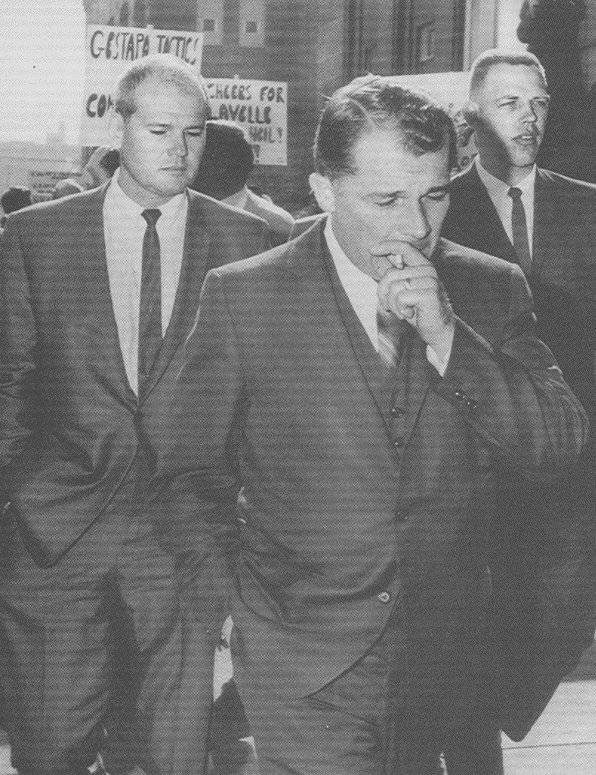

Famous TrailsF. Lee Bailey and Sam Sheppard (behind) at the 1966 trial.

Luckily, a polygraph expert from Boston named F. Lee Bailey was interested in Sheppard’s case.

Sheppard’s Acquittal

Norbert J. Yassanye, Plain Dealer Historical Photograph CollectionSam Sheppard with his son Chip (left) and second wife upon his acquittal.

Bailey took Sheppard’s case to the Supreme court. He claimed that the doctor’s constitutional right to a fair trial had been violated. Sheppard got a retrial in front of Judge Karl Weinman who Bailey described as “the best thing that happened to Sam Sheppard.”

While Weinman reviewed the entire trial record, a valuable piece of information fell into Bailey’s lap. In March 1964, Dorothy Kilgallen, who had written a daily column on Sheppard’s first trial, recalled that Judge Blythin had told her before the trial even began that Sheppard was “guilty as hell and the trial was a mere formality.”

This deposition helped Judge Weinman to declare a mistrial. He noted that the press coverage had been “calculated to inflame and prejudice.”

On Nov. 16, 1966, after a decade in prison, 40-year-old Sam Sheppard was released.

One week later, he was married to a German woman from Dusseldorf named Adriane Tabbenjohanns, who had corresponded with Sheppard while in prison. Tabbenjohanns’ would prove to add her own small bit of controversy to Sheppard’s case when it was discovered that her half-sister had been the wife of Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister.

The acquittal was a hollow victory for Sheppard. With the conviction overturned, Sheppard had his medical license reinstated, but soon after, he faced malpractice suits after two of his patients died while in surgery. Sheppard’s second wife divorced him and Sheppard entered a downward spiral of depression and alcoholism.

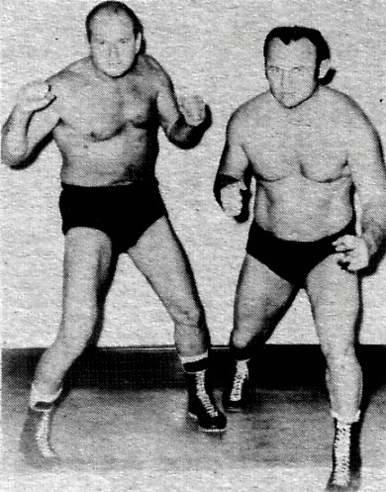

He entered professional boxing for a while, where he met his third wife, the 19-year-old daughter of his wrestling coach. On April 6, 1970, he died from liver failure. Dr. Sam Sheppard was just 46.

A Clean Legacy For Sam Sheppard?

Wiki FandomSheppard (left) wrestled over 40 matches before he died in 1970.

Sheppard’s son, Sam Jr., was determined to restore his father’s reputation and find his mother’s real killer.

He discovered that a mentally disturbed man named Richard Eberling who frequently washed his parent’s windows and was serving time for killing an elderly woman. Suspicious, Sam Jr. went to meet Eberling.

Though he denied killing Marilyn, Eberling drew an obsessively detailed map of the Sheppard family home. He even included a little-known entrance into the basement that wasn’t even present in the police sketch.

Sam Jr. approached Cleveland attorney Terry Gilbert to help uncover further information about his possible suspect. Gilbert found sealed police records that revealed Eberling had been arrested five years after Marilyn’s murder for burglaries. Two of Marilyn’s rings were found in his possession. It appeared Eberling had stolen them from a box of Marilyn’s possessions stored in the house of one of Sam Sheppard’s brothers.

In 1997, Sam Jr. and Gilbert filed a civil suit against the county for wrongful imprisonment of his father and to consider Eberling the real suspect.

Eberling died in prison in 1998. The jury ultimately ruled that they were unconvinced of Sam Jr.’s claims. Dr. Sheppard remained the likeliest suspect in the brutal murder of his own wife in the eyes of the law.

The Fugitive

On Aug. 29, 1967, 78 million viewers tuned in to watch Dr. Richard Kimble of the hit TV series The Fugitive finally confront his wife’s killer, the mysterious one-armed man. The 1967 series finale was one of the most watched television finales of all time and would later become the subject of a blockbuster Hollywood thriller starring Harrison Ford.

It had been four long years for the escaped fictional fugitive Dr. Kimble, and four gripping seasons for viewers. Kimble finally got his man and was exonerated for the wrongful conviction of his wife’s murder.

Though the shows’ producers denied it, The Fugitive bears striking similarities to the story of Dr. Sam Sheppard, except the true crime is perhaps even more compelling and lasted way longer than four seasons.

After this look at the grueling trial of Sam Sheppard, check out these vintage crime scene photos. Then, read about this novelist who wrote “How to Murder Your Husband” and was then arrested for murdering her husband.