So many prospectors flocked to San Francisco during the gold rush in California that the city's population rose from 1,000 to 25,000 between 1848 and 1849.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 sparked one of the most significant events in United States history and transformed San Francisco from a sleepy port town of approximately 1,000 residents into a booming metropolis within just a few years. The California gold rush forever changed the American West, but San Francisco’s gold rush evolution was perhaps the most drastic.

In 1848, San Francisco was barely a blip on the map. The area that would become the state of California had only just been acquired by the U.S. when Mexico ceded the land in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on Feb. 2, 1848. Word hadn’t yet spread that just a week earlier, a carpenter building a sawmill near the town of Coloma had found gold.

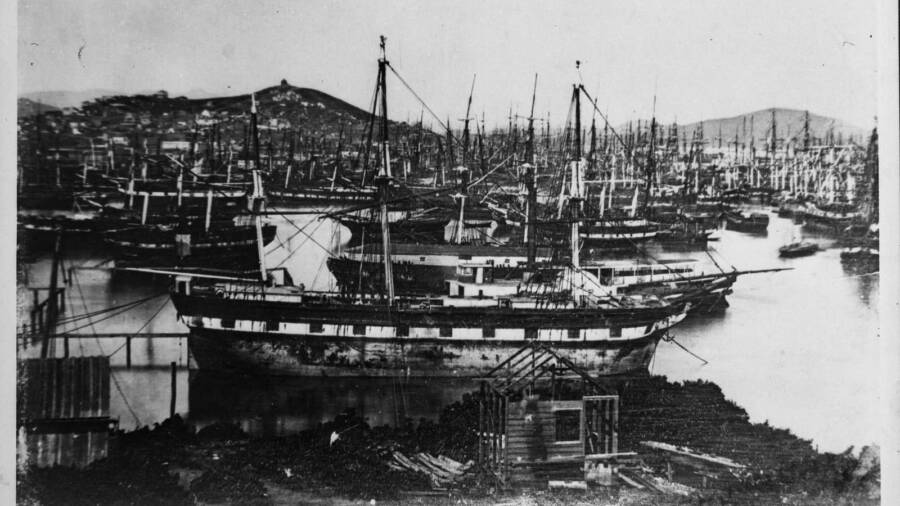

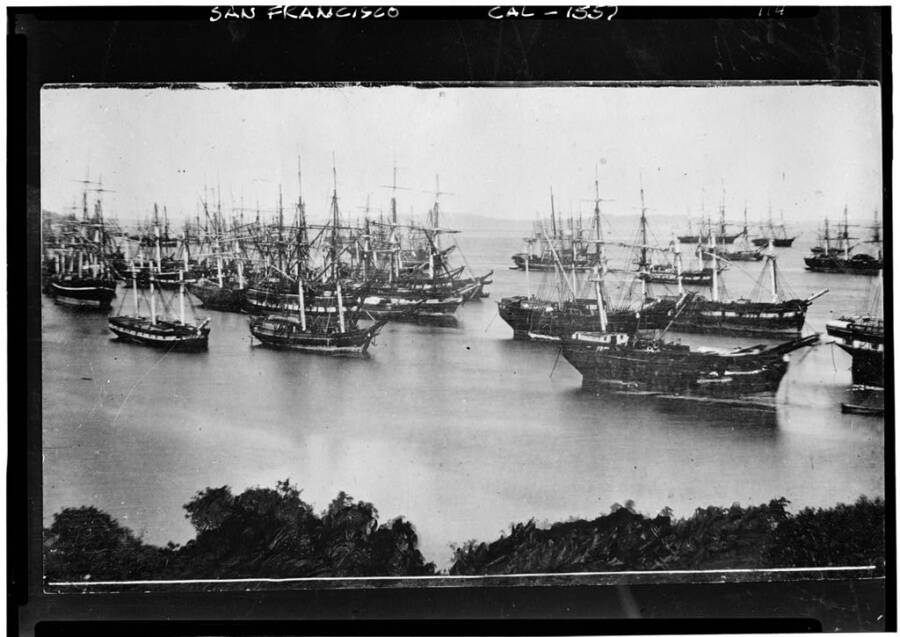

The news reached San Francisco that May, and the entire city was all but deserted by the end of the month as everyone rushed east in hopes of striking it rich. Ships brought thousands of prospectors from around the world to San Francisco Bay — and their crews promptly abandoned them to seek gold themselves.

By the mid-1850s, most miners had moved on, but the changes caused by the gold rush in San Francisco were permanent. The population had risen to more than 30,000; hundreds of stores, saloons, gambling halls, hotels, and other businesses had opened; and the nation’s first Chinatown had been established by immigrants who arrived in the U.S. through San Francisco to find work in mines and on the transcontinental railroad. The gold rush also accelerated California’s journey to statehood, radically altering the landscape of the American West.

The Onset Of The Gold Rush In San Francisco

On Jan. 24, 1848, James W. Marshall came across gold flakes while building a sawmill for John Sutter along the American River. Though Sutter attempted to keep the discovery a secret, the news spread rapidly.

Four months later, on May 12, a businessman named Sam Brannan marched through the streets of San Francisco holding a vial of the precious metal and shouting, "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!" Before making this announcement, Brannan had shrewdly purchased every pick, shovel, and pan between San Francisco and Sacramento, and he made a tidy profit reselling them to hopeful prospectors at a hefty markup.

At the time, San Francisco had fewer than 1,000 residents. By the end of May, almost all of them had rushed east to search for gold, and the city was essentially deserted — but not for long.

According to the Museum of the City of San Francisco, on May 29, 1848, The Californian published an editorial that read: "The whole country from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and from the sea shore to the base of the Sierra Nevadas, resounds with the sordid cry of gold, GOLD, GOLD! while the field is left half-planted, the house half-built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes."

The newspaper also announced that it was ceasing publication because its entire staff had left to search for gold.

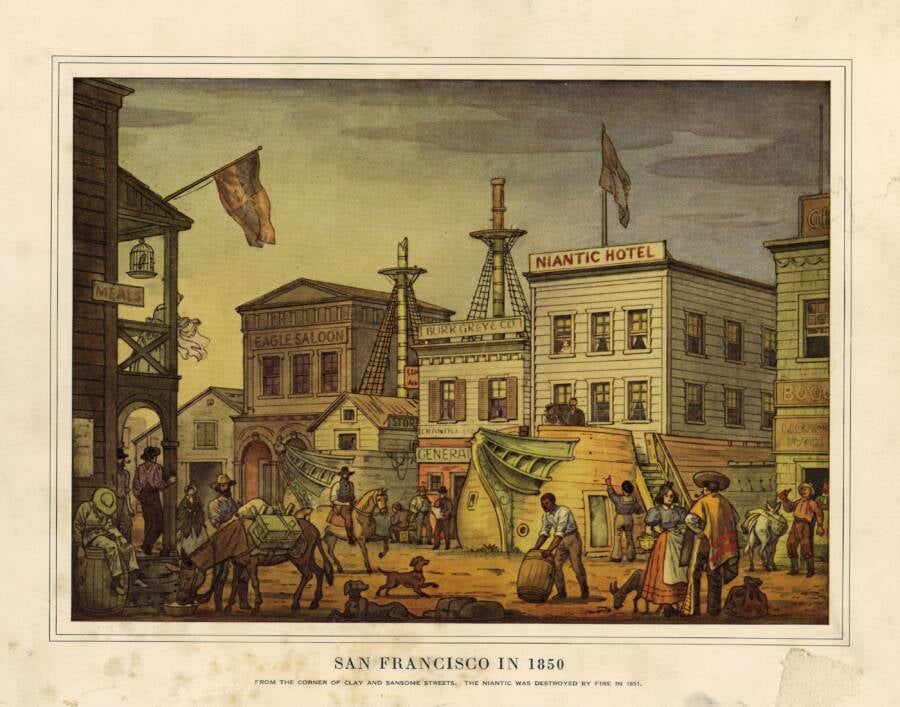

Oakland Museum of CaliforniaAn illustration of San Francisco in 1850. Niantic Hotel, which was destroyed by fire the following year, was built atop one of the ships abandoned in the bay during the gold rush.

However, the real frenzy began after Dec. 5, 1848, when President James Polk confirmed the rumors of gold that had reached the East Coast in his address to Congress, stating, "The accounts of abundance of gold are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service."

Polk's address convinced skeptics. Suddenly, "gold fever" overtook the U.S., and more and more people flocked to California to seek out the precious metal.

Ships began arriving in San Francisco Bay carrying prospectors from around the world. However, the crews of these vessels headed inland along with the passengers, leaving the boats deserted in the harbor. By June 1849, some 200 abandoned ships were floating near the city. Some of them were brought ashore to serve as dwellings, warehouses, and businesses, such as the Niantic Hotel.

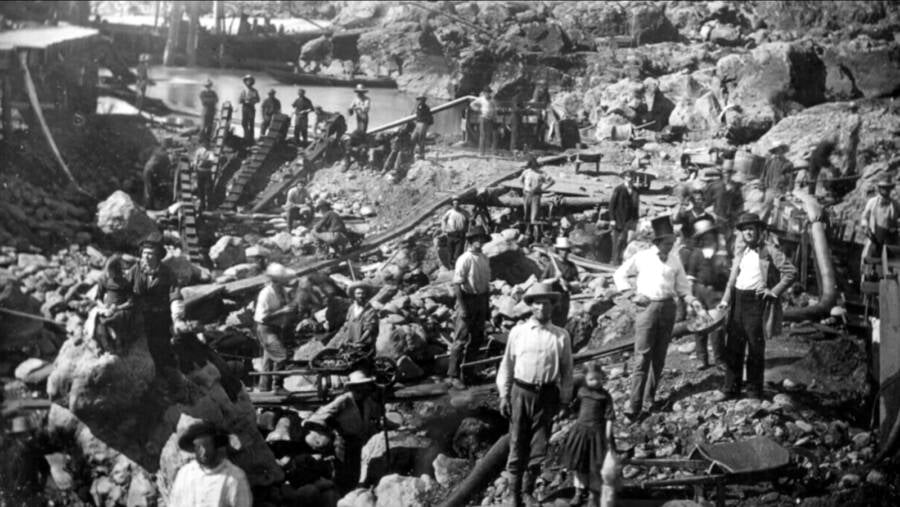

In 1849, an estimated 40,000 people poured into San Francisco by land or sea. They became known as "49ers," and they were the driving force behind San Francisco's gold rush.

The 49ers, The Pioneers Who Risked Everything For Gold

Most 49ers were young men in their 20s and 30s who left behind families, jobs, and established lives for the chance at striking it rich. Some of them traveled from the East Coast of the U.S. around Cape Horn, a journey that could take up to eight months. Others took a shortcut through Panama, crossing the isthmus on foot or horseback before boarding a second ship on Panama's west coast that would take them to San Francisco. A smaller number of prospectors made the perilous journey by land, trudging through the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and deserts in a wagon.

Then, there were the international prospectors. They arrived from Mexico, Chile, Peru, China, Australia, France, Ireland, Germany, and many other places around the world. This unprecedented international migration created a multilingual, multicultural society in San Francisco and the gold fields.

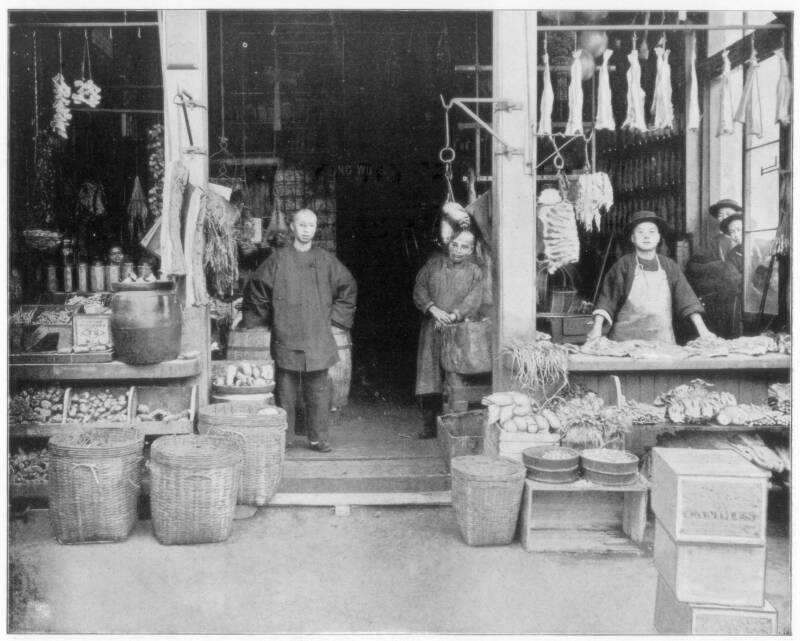

Public DomainSan Francisco's Chinatown in the late 1800s.

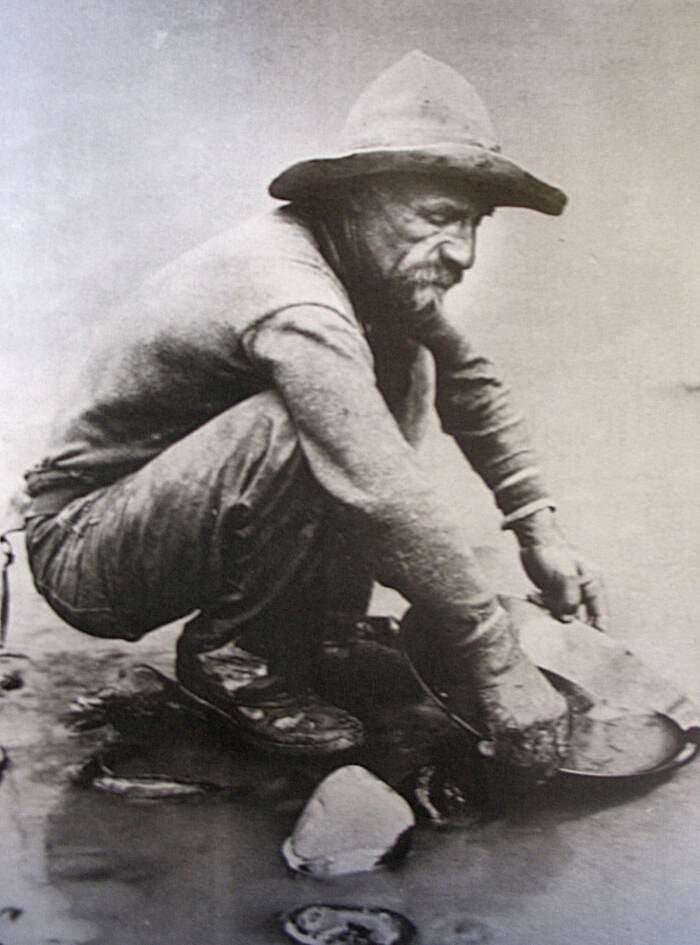

However, the reality of mining life quickly dispelled romantic notions of easy wealth. These 49ers had to deal with diseases — particularly cholera and dysentery — malnutrition, harsh weather, claim jumping, and violence. Few of them struck it rich. Some estimates suggest only one in 20 prospectors found a significant amount of gold, while merchants selling supplies often made more reliable profits.

"We soon found that, although, in imagination, it might be agreeable work, yet in reality, it was the most laborious and in the majority of cases the most unsatisfactory that men could be engaged in," one gold-seeker, Augustin Hibbard, wrote to his brother in 1850.

By the early 1850s, many disappointed 49ers had returned home or moved on to other opportunities. Those who remained often transitioned from independent mining to wage labor for large mining operations or found other jobs in California's growing economy.

However, even as the arrival of prospectors slowed, the changes that occurred San Francisco during the gold rush had put the quiet port town on the path to become the major city it is today.

The Rapid Transformation Of San Francisco During The Gold Rush

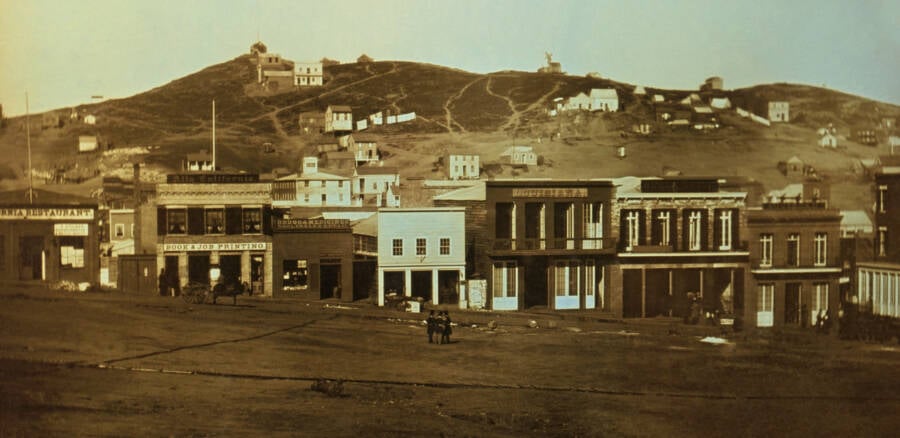

At the outbreak of the gold rush, San Francisco consisted of a few dozen buildings clustered around Portsmouth Square. Within just a few years, it had over 500 streets, 20 wharves extending into the bay, and block upon block of substantial brick and stone buildings.

This rapid development occurred despite devastating fires that repeatedly leveled portions of the city. The most destructive, on May 3, 1851, destroyed about three-quarters of San Francisco, yet rebuilding began almost immediately.

San Francisco's unique topography presented challenges that were overcome through ambitious engineering solutions. The hilly terrain was partially flattened through steam-powered excavation, with the removed soil used to fill in the shallow parts of the bay, expanding the city's footprint. Stump-filled, muddy streets were covered with wooden planks, creating elevated roadways.

Public DomainShips abandoned in San Francisco's Yerba Buena Cove after gold fever took over.

Come 1853, the boomtown was home to substantial cultural amenities, including multiple theaters hosting international talent, several daily newspapers, dozens of hotels, and multiple churches representing a variety of denominations.

The city also quickly established trade networks across the Pacific. Steamships established regular service to Panama, and other vessels frequently traveled between San Francisco and ports in China, Australia, and other Pacific countries. This international interaction distinguished San Francisco from other American cities of a similar size.

On top of this, San Francisco rapidly developed manufacturing, with iron foundries, furniture factories, and flour mills operating by the early 1850s. Banking likewise emerged as a critical industry, with the first bank opening in January 1849, followed by the establishment of major institutions like Wells Fargo (1852) and the San Francisco branch of the United States Mint (1854).

Even when the initial gold rush fervor had subsided, San Francisco remained the unquestioned commercial capital of the American West, a position it would maintain throughout the rest of the 19th century.

How The Gold Rush Helped Shape San Francisco's Identity

Culturally, the California gold rush also created a unique, diverse identity for San Francisco. Since gold fever had summoned people from all over the world to converge on the city, the influence of these various cultures was seen as San Francisco rapidly developed.

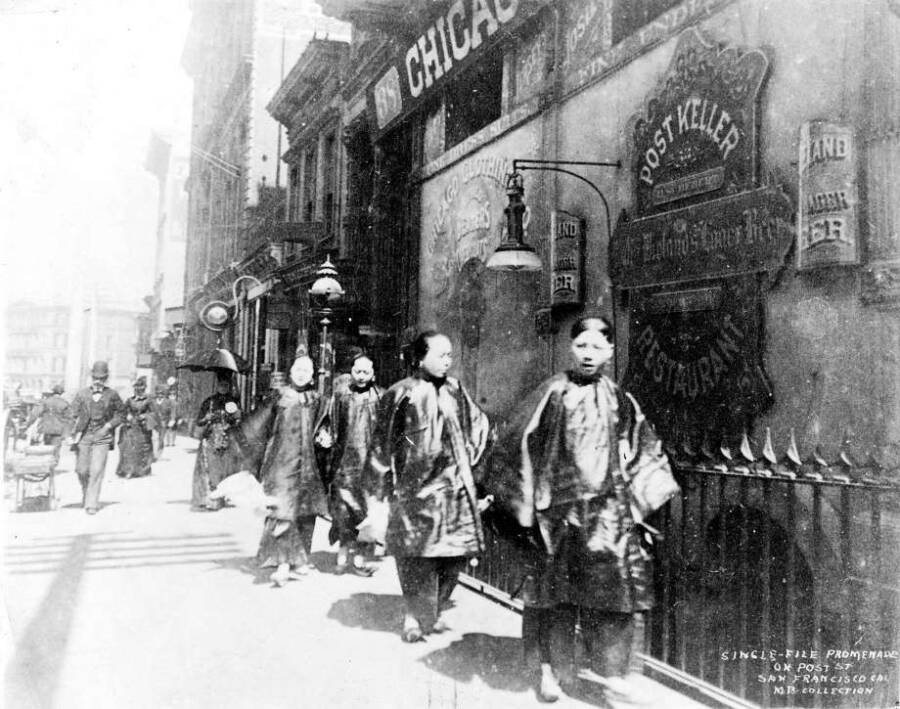

Chinese immigrants, in particular, made up a substantial portion of San Francisco's population. Higher taxes in China following the Opium Wars forced many peasants and farmers off their land, and they saw the gold rush as a chance at a new beginning in America. In fact, in 1852 alone, more than 20,000 Chinese immigrants moved into the San Francisco area.

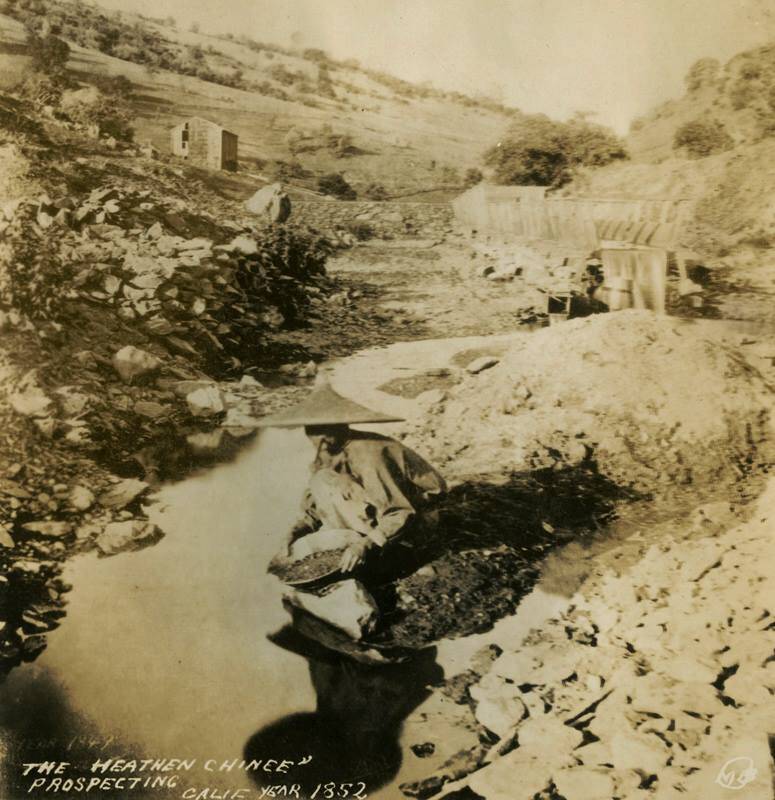

Public DomainA gold rush photo with the original caption: "The Heathen Chinee Prospecting." 1852.

Of course, they weren't welcomed with open arms by all. One American miner remarked at the time, "Chinamen are getting to be altogether too plentiful in this country." In May 1952, a $3-per-month levy was directed at Chinese miners as part of the Foreign Miners Tax, increasing the violence directed toward the immigrants.

Still, this influx of Chinese workers did lead to the establishment of San Francisco's Chinatown — the oldest in the U.S. — which left a permanent mark on the city's culture. By 1870, the majority of Chinese immigrants in America had settled in California, contributing more than $5 million to the state through the Foreign Miners Tax.

Thus, the gold rush in San Francisco and the international attention it drew made the city the bustling, diverse metropolis it is today.

After learning about the gold rush in San Francisco, see even more photos from the Klondike gold rush. Or, explore the Gilded Age in full color with our gallery of colorized photographs.