Everyone knows the biggies: Darwin, Newton, Mendeleev, Watson and Crick. But what about the lesser known scientific heroes?

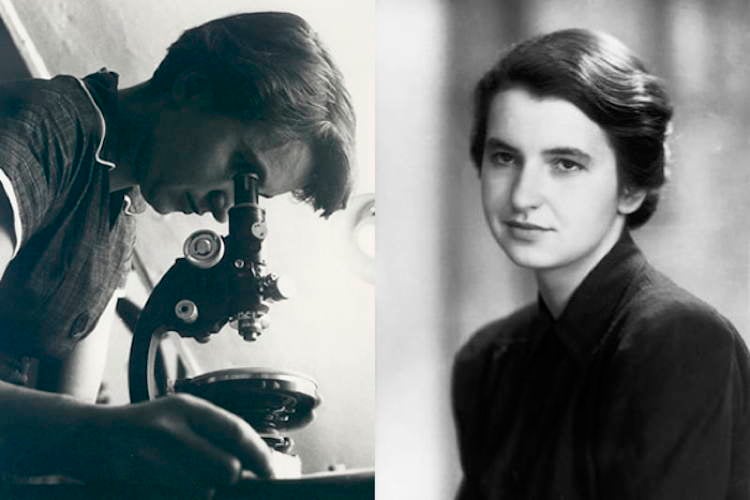

Scientific Heroes: Rosalind Franklin

We all know the scientific greats; Darwin and his theory of evolution, Newton and his laws of gravity. But there are droves of unsung heroes of the scientific world whose works deserve much recognition. Rosalind Franklin is one of them. As a molecular biologist, Franklin was responsible for the original research behind the discovery of DNA’s structure.

Source: WordPress

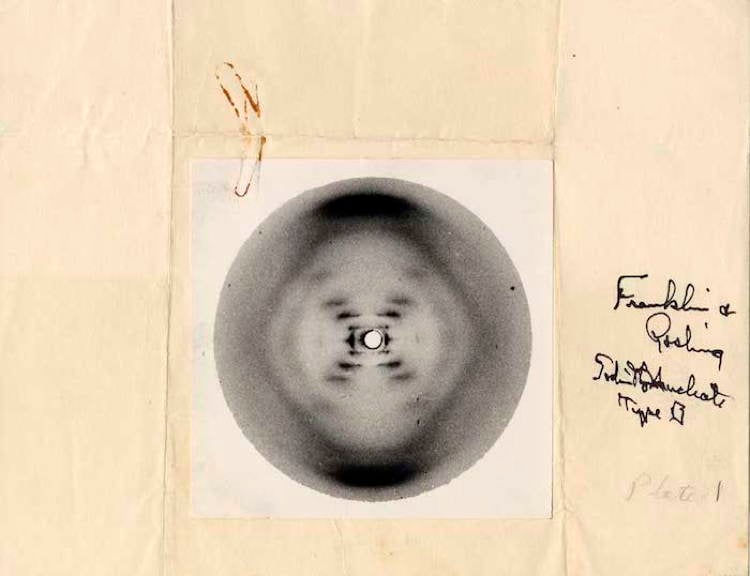

Franklin’s crystallography snapshots featured images of DNA structure that hadn’t ever been seen before. So ahead of her time was Franklin that she passed away years before Watson and Crick went on to win a 1962 Nobel prize for their DNA double-helix model; a feat which, as Crick readily admitted, wouldn’t have been possible without her vital research.

While many of her independently-researched papers on DNA’s structure went unpublished, it was the language within them that greatly informed Watson and Crick’s own reports on the subject. Franklin went on to contribute much research on the tobacco mosaic virus as well as polio. Her pioneering life was cut short in 1957, though, as she died at age 37 of ovarian cancer.

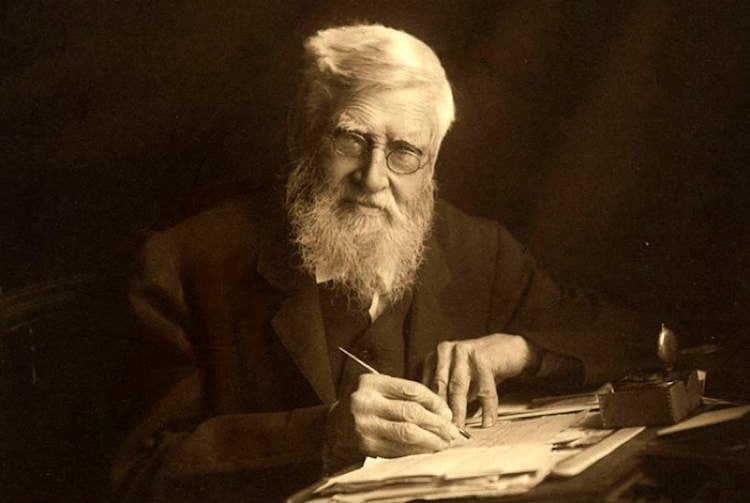

Scientific Heroes: Alfred Russel Wallace

Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of Species is largely considered the most important paper on evolution ever produced, but there is in fact another scientist who, to this day, remains a forgotten father of biogeography.

Alfred Russel Wallace was a British explorer and naturalist who independently thought up the theory of evolution by natural selection. After recording his fieldwork expedition findings in Malaysia in the mid-1800s, Wallace sent his work to his confidant Charles Darwin for a second opinion.

Source: Natural History Museum

The work inspired Darwin to write his own ideas on evolution, and he published his thoughts along with Wallace’s findings in a joint paper, before going on to write his own paper on the theory in 1858.

As Darwin has became known as the sole scientific superpower behind the theory of evolution, no one ever really gave Wallace the same kind of recognition, despite his discovery of thousands of new animal species or his journal, “The Malay Archipelago” being considered the best scientific exploration journal published in the 19th century.

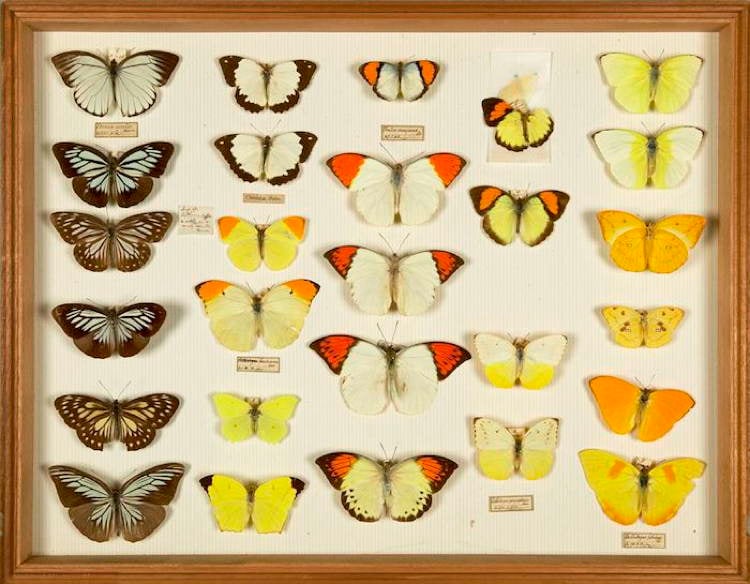

Why such disparity in outcomes? Unlike his contemporaries, when Wallace’s investments failed, he had no family wealth or name on which he could fall back. In any event, Wallace’s butterfly and beetle collections can still be seen in the Natural History Museum today.

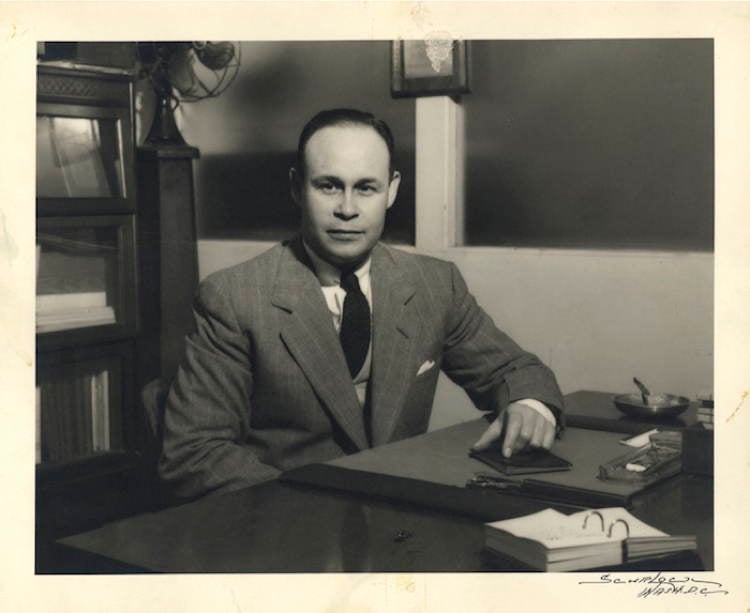

Scientific Heroes: Charles Drew

Source: National Institute Of Health

Blood transfusions have helped save countless lives over the last 70 years, but little is known about the pioneering physician who discovered the process. Charles Drew was an African-American surgeon who fought racial prejudices to bring blood transfusion to the masses.

He carried out revolutionary research that led him to discover that blood could in fact be preserved and reconstituted later when it was needed.

Source: National Institute Of Health

Drew came up with an ingenious system of storing the substance, which he called ‘blood banks’. These new centers changed the medical world, and mobile units were developed which could transport the vital blood types across the USA. So essential were Drew’s services that they culminated in the first ever blood drive during World War II to treat soldiers on the front line in both the States and in Britain. Without Drew’s work, hundreds of thousands of lives would have been lost.

Drew’s life came to a sudden halt in 1950, when he was fatally injured in a car accident. Oddly enough, it is a blood transfusion—or lack of one—that swirls about urban legends regarding Drew’s death. Some believe that due to Drew’s race, he was denied a potentially life-saving blood transfusion.

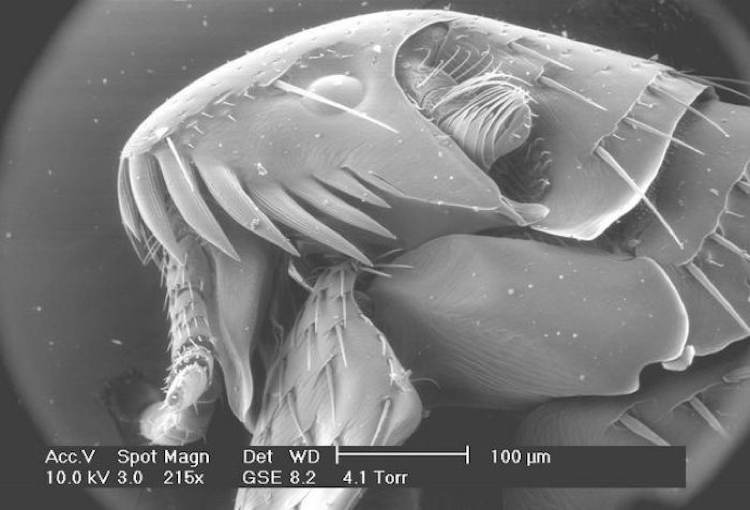

Scientific Heroes: Miriam Rothschild

Not every scientific discovery has to change the entire world to be significant. In fact, some of the greatest discoveries are those which lurk beneath the microscopes, and some of the greatest scientists are those who successfully convey the importance of the visually minuscule in a global context.

Miriam Rothschild is one such scientific hero. A renowned entomologist and botanist, Rothschild’s study of insects stood at the forefront of the natural inquiry. Having grown up in gardens full of wild flora and fauna, Rothschild’s interest in insects was engrained into her consciousness from an early age.

As she grew older, Rothschild continued to study the world of butterflies and bugs in greater detail until one day, she made a breakthrough while studying the simple flea. Rothschild was the first to work out the flea’s jumping mechanism, and went on to become the foremost authority on the insect.

While it may not sound so significant, her work helped to demystify the nature of parasites and enabled scientists to contain the spread of fleas and other insects, which might otherwise feed off our prized pets.

However, for someone who lacked traditional schooling and hailed from a family of influential financiers, Rothschild never gained the scientific recognition she deserved and was often regarded as an amateur. More than 50 years and 350 papers later, Rothschild was made a Dame for her work within the microscopic kingdom. However, her lack of orthodox education has largely kept her out of the history books.

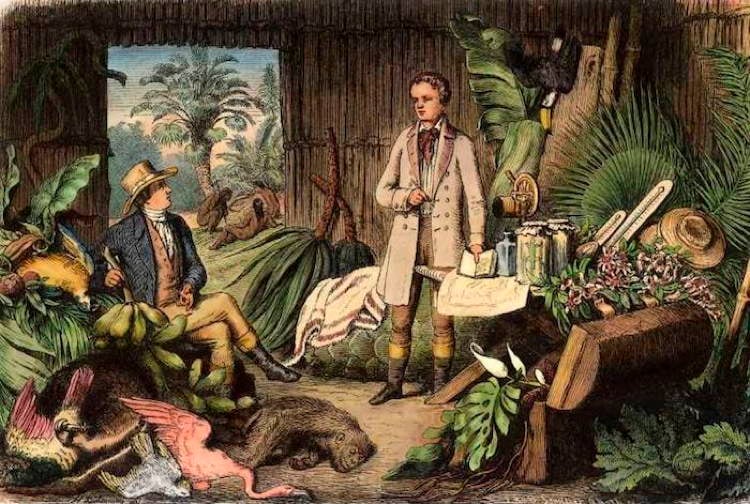

Alexander Von Humboldt

Described by Darwin as “the greatest scientific traveller who ever lived”, Alexander Von Humboldt was an intrepid explorer who is well regarded as one of the founders of modern geography. Humboldt trekked across Latin America for five years, meticulously mapping over 1700 miles worth of flora and fauna covered land.

His travels saw him traverse the great white ridges of the Cordillera Real, a treacherous range of frozen mountains and bravely cross the bursting banks of the formidable Magdalena River. His journey was one of the most dangerous scientific expeditions, but the risk paid off.

Source: University Of Texas

Humboldt’s tropical trek led to the discovery of “isothermal lines”, which allowed him to compare climate change across countries. Despite his large contributions to science, he still remains something of an unsung hero. Humboldt’s research into weather and how habitats changed in high altitudes was leaps and bounds ahead of his time, and laid the foundations for physical geography and meteorology today; a discovery which mankind could not live without.

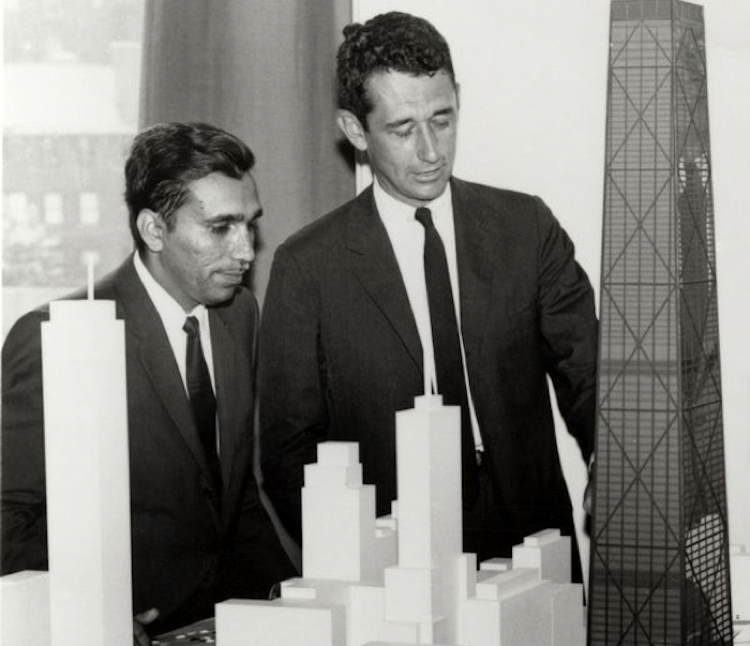

Scientific Heroes: Fazlur Khan

Source: Lehigh University

From scientific study to structural engineering, Fazlur Khan is thought to be one of the most influential architects of the 20th century. Chances are you’ll recognize his work or have even walked past it. Even still, the innovator isn’t nearly as well recognized as some of his construction counterparts. The man behind the John Hancock Center and Willis Tower in Chicago, Khan is responsible for the second tallest building in North America and for the structural system behind all of today’s towers.

Source: Lehigh University

In other words, the soaring skyscrapers that define our skylines wouldn’t be possible without the structural skill of Fazlur Khan. Known as the “Einstein of structural engineering”, he also pioneered the use of computer-aided architectural design, leaving behind a legacy of innovation that others can only dream of matching.

A true visionary of our conception of the modern world, Khan may not be mentioned in history books, but his focus on vertical growth lives on in cities around the world.

After this look at scientific greats, read the story of the tragically overlooked scientist Hypatia of Ancient Greece. Finally, check out 24 Isaac Newton facts you’ve never heard before.