Historians disagree on how cruel Shaka truly was as a ruler, but his military prowess was indisputable.

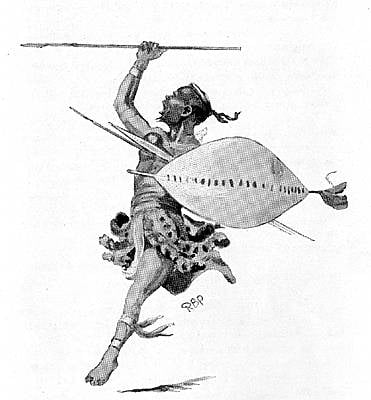

Wikimedia CommonsA rendering of Shaka, founder of the Zulu empire.

Shaka, chieftain of the Zulu tribe, was described as the “African Napoleon” for his military genius and consolidation of hundreds of South African tribes under the Zulu Empire. Though short-lived, Shaka left quite a legacy following his turbulent and by some accounts, cruel, reign.

Who Was Shaka?

Shaka, king of the Zulus, was born around 1787 to the Zulu chief Senzangakhona KaJama, and Nandi, of the neighboring Langeni clan. One popular narrative is that Shaka’s conception was a mistake after his parents got carried away during uku-hlobonga, a ritual for unmarried couples involving sexual foreplay and no penetrative sex. When Zulu elders including Senzangakhona himself discovered that Nandi was pregnant, they tried to deny it. Senzangakhona claimed that Nandi’s bloated belly was a symptom of iShaka, an intestinal and parasitic beetle.

Shaka, or Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was given his name as a constant reminder of his illegitimacy, and at age six, Shaka and his mother were exiled from his father’s kraal, a traditional African village of huts, or court.

Shaka and his mother returned to her home where they were unwelcome and eventually driven out to join a different tribe entirely, the Mthethwa. In his late teens, Shaka was assigned an amabutho, or a military regiment of young men separated based on age group. Each amabutho was called upon when needed for combat, labor, policing, or hunting.

During this time he caught the attention of premier chieftain, Dingiswayo. Shaka displayed great valor, skill, and strength. An impressed Dingiswayo became a sort of mentor to him.

The Young Warrior

Shaka got his first taste of warfare at age 21. By then, he was a powerhouse of all muscle standing at six feet and three inches. Shaka was equipped with three assegais, or “light spears,” for throwing and a five-foot, 9-inched oval shield. He was clad with a kilt of fur stripes, a skin cape with black widow-bird feathers, cowhide sandals and white oxtails around his ankles and wrists.

Intertribal battles of the time were a show of strength with very little bloodshed. The two opposing sides would face each other at 40 or 50 yards and hurl their assegais until one side fled. Even if pursued the fleeing side just had to drop their assegais and surrender and their lives would be spared.

Wikimedia CommonsLarge statue of Shaka at Camden Market in London, England.

Shaka quickly displayed his innate ability for warfare and began to alter the combat tools he was issued. First, he discarded his cowhide sandals because they could make him lose his balance. With increased agility, Shaka could engage an enemy at close quarters. He deflected spears with his shield then charged in for the kill. Hooking the enemies’ shield aside with his own he could then plunge his assegai into his victim.

He also fashioned his own weapon with a short, thick handle and a massive blade. In effect, he had created a sword. Shaka called it the iklwa because of the sound it made when it was thrust and pulled out of someone’s body.

He became known as Nodumehlezi, “the one who when seated causes the earth to rumble.”

Shaka’s successfully defeated the army of Zwide, the chief of the Ndwandwe tribe, which won him a generous share of captured cattle. Chief Dingiswayo, in turn, made Shaka his commander in chief, and more importantly, helped organize a reconciliation between Shaka and his estranged father, Senzangakhona.

Senzangakhona made Shaka his heir, but before his assassination in 1816 one of his wives convinced him to make Shaka’s half-brother Sigujana his successor instead. But the young warrior did not let it stand. With the help of one of Dingiswayo’s regiments, Shaka killed Sigujana and took charge of the 1,500 Zulus. They were among the smallest of the more than 800 clans — but under Zulu, this would all change.

A United Zulu Kingdom

His new domain extended 100 square miles. Shaka still remained a subordinate to Dingiswayo until the chief died at the hands of Zwide in 1817.

Dingiswayo’s death resulted in many Mthethwa defecting to the Ndwandwe, while others joined Shaka. Zwide proved a formidable enemy to him in the beginning, but the young warrior chief’s superior military strategy would score a major victory against the Ndwandwe the following year.

Wikimedia CommonsDepiction of a Zulu warrior under Shaka’s command.

This success allowed Shaka the freedom to pursue alliances with other tribes and he consolidated his power while he grew his army.

The young Zulu king was known for his cruelty. The general consensus among historians is that as he formed more alliances, defeated more chiefs, and expanded the Zulu Kingdom, he became a brutal despot. He demanded loyalty from his warriors. Should anyone insult his mother or him he condemned them to death by clubbing, spearing, head-twisting or impaling.

But he remained peaceful to white colonialists and even sent delegates of his domain to visit them. Under his reign, there were no conflicts between the Zulu people and white traders. Though the British did negotiate control over the Port Natal — now the city of Durban in South Africa — they made no attempt to challenge Shaka. It wouldn’t be until after Shaka’s death that bloody conflicts between his people and the Dutch-Afrikaner settlers known as the “Boers” began.

The warrior king ruled without rival over 250,000 people for ten years. He could assemble more than 50,000 warriors at a time and it is said that he was responsible for the deaths of some two million people by warfare alone.

When his mother died in 1827, some say that the Zulu king lost his mind. Overcome with grief, Shaka Zulu outlawed farming and the use of milk for a year. Pregnant women and their husbands were murdered.

Perhaps fed up, Shaka’s half brother, Dingawe, assassinated the young tyrant in 1828. He then assumed the throne himself and murdered all Zulus who were likely to remain loyal to Shaka Zulu. He had his half-brother’s body buried in an unmarked grave.

Disputed History

But in recent years, historian Dan Wylie has challenged this narrative of the Napoleonic African king. His book, Myth of Iron: Shaka In History, posits that almost every book written on Shaka over the last 170 years has been drawn from the distorted and embellished works of two colonial writers Nathaniel Isaacs and Henry Francis Fynn.

Isaacs even wrote to Fynn advising him to make the Zulus “out to be as bloodthirsty as you can and endeavor to give an estimation of the number of people they have murdered during their reign[s].” This would not only boost sales of Fynn’s book but also help to justify colonials usurping Zulu lands.

Wylie, as well as other scholars, have doubted that Shaka was illegitimate, that he revolutionized African warfare, and that he was as violent as he was made out to be. But even Wylie concedes that as far as the history of the warrior chief goes, “There is a great deal that we do not know and will never know.”

You can also watch a much-disputed 1986 miniseries, Shaka Zulu, on the reign of Shaka now available on Netflix.

After learning about the real Shaka Zulu, check out this gallery of African kingdoms like Shaka’s just before the invasion of European colonials. Then, read about the fearless west African leader, Queen Nzinga, who fought off slave traders.