Simón Bolívar freed South America's slaves — but he was also a wealthy descendent of Spaniards who believed in the interests of the state over the interests of the people.

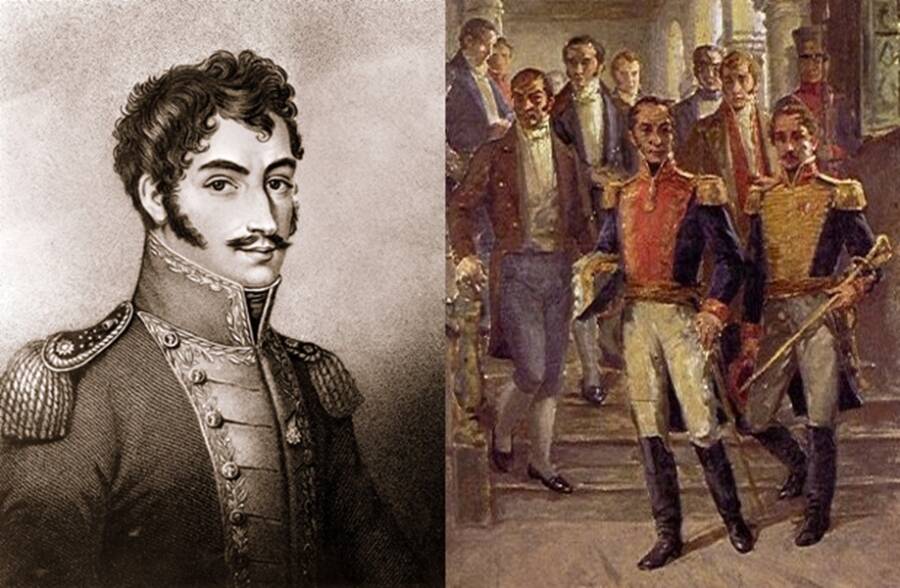

Wikimedia CommonsSimón Bolívar was a Venezuelan general who led the South American rebellion for independence.

Known across South America as El Libertador, or the Liberator, Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military general who led South America’s fight for independence against Spanish rule in the early 19th century.

During his lifetime, he was both revered for his firebrand rhetoric promoting a free and united Latin America, and reviled for his tyrannical proclivities. He freed thousands of slaves, but killed thousands of Spaniards in the process.

But who was this South American idol?

Who Was Simón Bolívar?

PicrylBorn into a wealthy Creole family, Simón Bolívar rose as a prominent leader of the revolution.

Before he became the fierce liberator of South America, Simón Bolívar lived a carefree life as the son of a wealthy family in Caracas, Venezuela. Born on July 24, 1783, he was the youngest of four children and was named after the first Bolívar ancestor who migrated to the Spanish colonies some two centuries before his birth.

His family came from a long line of Spanish aristocrats and businessmen on both sides. His father, Colonel Juan Vicente Bolívar y Ponte, and his mother, Doña María de la Concepción Palacios y Blanco, inherited vast swaths of land, money, and resources. The Bolívar family fields were labored over by the Native American and African slaves that they owned.

Little Simón Bolívar was petulant and spoiled — though he suffered great tragedy. His father died of tuberculosis when he was three, and his mother died from the same disease about six years later. Because of this, Bolívar was mostly cared for by his grandfather, aunts and uncles, and the family’s longtime slave, Hipólita.

Hipólita was doting and patient with the mischievous Bolívar, and Bolívar unabashedly referred to her as the woman “whose milk sustained my life” and “the only father I have ever known.”

Wikimedia CommonsWhen he was young, Simón Bolívar was a spoiled boy with little regard for authority.

Soon after his mother died, Simón Bolívar’s grandfather passed away, too, leaving Bolívar and his older brother, Juan Vicente, to inherit the enormous fortune of one of Venezuela’s most prominent families. Their family’s estate was estimated to be worth millions in today’s dollars

His grandfather’s will appointed Bolívar’s uncle Carlos as the boy’s new guardian, but Carlos was lazy and ill-tempered, unfit to raise children or command such a mountain of wealth.

Without adult supervision, the rambunctious Bolívar had the freedom to do as he pleased. He ignored his studies and spent much of his time roaming around Caracas with other children his age.

At the time, Caracas was on the cusp of a serious upheaval. Twenty-six thousand more black slaves were brought to Caracas from Africa, and the city’s mixed-race population was growing as a result of the inevitable intermingling of white Spanish colonizers, black slaves, and native peoples.

There was growing racial tension in the South American colonies, since the color of one’s skin was deeply tied to one’s civil rights and social class. By the time Bolívar reached his teens, half of Venezuela’s population was descended from slaves.

Underneath all of that racial tension, a yearning for freedom began to simmer. South America was ripe for rebellion against Spanish imperialism.

His Education Of The Enlightenment

Bolívar’s family, although one of the wealthiest in Venezuela, was subject to class-based discrimination as a result of being “Creole” — a term used to describe those of white Spanish descent who were born in the colonies.

By the late 1770s, Spain’s Bourbon regime had enacted several anti-Creole laws, robbing the Bolívar family of certain privileges only afforded to Spaniards born in Europe.

Still, being born into an upper-crest family, Simón Bolívar had the luxury of travel. At age 15, the heir apparent to his family’s plantations, he went to Spain to learn about empire, commerce, and administration.

Wikimedia CommonsThe death of Simón Bolívar’s wife, María Teresa, was a turning point in the young man’s life, leading him to a life of politics.

In Madrid, Bolívar first stayed with his uncles, Esteban and Pedro Palacios.

“He has absolutely no education, but he has the will and intelligence to acquire one,” Esteban wrote of his new charge. “And even though he spent quite a bit of money in transit, he landed here a complete mess….I am very fond of him.”

Bolívar wasn’t the most considerate guest, to say the least; he burned through his uncles’s modest pensions. And so he soon found a more suitable patron, the marquis of Uztáriz, another Venezuelan who became young Bolívar’s de facto tutor and father figure.

The marquis taught Bolívar math, science, and philosophy, and introduced him to his future wife, María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alayza, a half-Spanish, half-Venezuelan woman two years Bolívar’s senior.

They had a passionate, two-year courtship in Madrid before finally getting married in 1802. The newly wed Simón Bolívar, 18 and ready to take over his rightful inheritance, returned to Venezuela with his new bride in tow.

But the quiet family life he envisioned would never become. Just six months after arriving in Venezuela, María Teresa succumbed to a fever and died.

Bolívar was devastated. Though he enjoyed many other lovers in his lifetime after María Teresa’s death — most notably Manuela Sáenz — María Teresa would be his only wife.

Later, the renowned general credited his career change from businessman to politician to the loss of his wife, as many years later Bolívar confided to one of his commanding generals:

“If I were not widowed, my life would have maybe been different; I would not be the General Bolívar nor the Libertador….When I was with my wife, my head was filled only with the most ardent love, not with political ideas….The death of my wife placed me early in the road of politics, and caused me to follow the chariot of Mars.”

Leading South America’s Liberation

Wikimedia CommonsWitnessing Napoleon’s crowning as king of Italy lit a fire under the young aristocrat’s belly.

In 1803, Simón Bolívar returned to Europe and witnessed the coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte as the King of Italy. The history-making event left a lasting impression on Bolívar and gave rise to his interest in politics.

For three years, with his most trusted tutor, Simón Rodríguez, he studied the works of European political thinkers — from liberal Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke and Montesquieu to the Romantics, namely Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

According to University of Texas at Austin historian Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Bolívar became “attracted…to the notion that laws sprang from the ground up, but could also be engineered from the top down.” He also became “familiar with…[the Romantics’] biting critique of the Enlightenment’s dangerous abstractions, like the idea that humans and societies were inherently reasonable.”

Through his own unique interpretations of all of these writings, Bolívar became a Classical Republican, believing that the interests of the nation were more important than the interests or rights of the individual (hence his dictatorial leadership style later in life).

He also recognized that South America was primed for revolution — it just needed a little nudging in the right direction. He returned to Caracas in 1807, ready to dive into politics.

His opportunity came soon enough. In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain and ousted its king, leaving Spanish colonies in South America without a monarchy. Colonial cities responded by forming elected councils, called juntas, and declared France the enemy.

In 1810, while most Spanish cities were self-ruling, juntas in and around Caracas joined forces — with the help of Bolívar and other local leaders.

Simón Bolívar, full of revolutionary ideas and armed with his wealth, was appointed as an ambassador for Caracas and went to London to gain British support for the cause of South American self-rule. He made the trip, but instead of forming a British allegiance he recruited one of Venezuela’s most revered patriots, Francisco de Miranda, who was living in London.

Miranda had fought in the American Revolution, was recognized as a hero of the French Revolution, and had met personally with the likes of George Washington, General Lafayette, and Russia’s Catherine the Great (Miranda and Catherine were rumored to be lovers). Simón Bolívar recruited him to help the independence cause in Caracas.

Although Bolivar wasn’t a true believer in self-rule — unlike his North American counterpart, Thomas Jefferson — he used the idea of the United States to rally his fellow Venezuelans. “Let us banish fear and lay the foundation stone of American liberty. To hesitate is to perish,” he proclaimed on July 4, 1811, America’s independence day.

Venezuela declared independence the next day — but the republic would be short-lived.

The First Republic Of Venezuela

Wikimedia CommonsSimón Bolívar and his vice president Francisco De Paula Santander.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, many of Venezuela’s poor and non-white people hated the republic. The nation’s constitution kept slavery and a strict racial hierarchy completely intact, and voting rights were confined to property owners. Plus, the Catholic masses resented the Enlightenment’s atheistic philosophy.

On top of public resentment toward the new order, a devastating series of earthquakes toppled Caracas and Venezuela’s coastal cities — quite literally. A massive uprising against the junta of Caracas spelled the end for the Venezuelan republic.

Simón Bolívar fled Venezuela — earning safe passage to Cartagena by turning in Francisco de Miranda to the Spanish, an act that would forever live in infamy.

From his tiny post on the Magdalena River, in the words of historian Emil Ludwig, Bolívar began “his march of liberation there and then, with his troop of two hundred half-caste Negroes and Indios…without any certainty of reinforcement, without guns…without orders.”

He followed the river, recruiting along the way, taking town after town mostly without combat, and eventually gained full control of the waterway. Simón Bolívar continued his march, leaving the river basin to cross the Andes mountains to take back Venezuela.

On May 23, 1813, he entered the mountain city of Mérida, where he was greeted as El Libertador, or The Liberator.

In what is still considered one of the most remarkable and dangerous feats in military history, Simón Bolívar marched his army over the highest peaks of the Andes, out of Venezuela and into modern-day Colombia.

Wikimedia CommonsSimón Bolívar earned the nickname El Libertador for his prolific role in the liberation of South America.

It was a grueling climb that cost many lives to bitter cold. The army lost every horse it had brought, and much of its munitions and provisions. One of Bolivar’s commanders, General Daniel O’Leary, recounted that after descending the far side of the highest summit “the men saw the mountains behind them…they swore of their own free will to conquer and die rather than retreat by the way they had come.”

With his soaring rhetoric and unflappable energy, Simón Bolívar had roused his army to survive the impossible march. O’Leary writes of the “boundless astonishment of the Spaniards when they heard that an enemy army was in the land. They simply could not believe that Bolivar had undertaken such an operation.”

But though he had earned his stripes on the battlefield, Bolívar’s wealthy status as a white Creole at times worked against his cause, especially compared to the fierce Spanish cavalry leader named José Tomás Boves who successfully amassed support from native Venezuelans to “squelch the people of privilege, to level the classes.”

Those loyal to Boves only saw that “the Creoles who lorded over them were rich and white…they hadn’t understood the true pyramid of oppression,” beginning at the top with imperial colonialism. Many natives were against Bolívar due to his privilege, and in spite of his efforts to liberate them.

In December 1813, Bolívar defeated Boves in an intense battle at Araure, but “simply couldn’t recruit soldiers as quickly and effectively as [Boves],” according to biographer Marie Arana. Bolívar lost Caracas soon afterward, and fled the continent.

He went to Jamaica, where he wrote his famous political manifesto known simply as the Jamaica Letter. Then, after surviving an assassination attempt, Bolívar fled to Haiti, where he was able to raise money, arms, and volunteers.

In Haiti, he finally realized the necessity of attracting poor and black Venezuelans to his side of the fight for independence. As Cañizares-Esguerra points out, “this isn’t due to principle, it’s his pragmatism that is moving him to undo slavery.” Without the support of slaves, he had no chance of ousting the Spanish.

Bolívar’s Fiery Leadership

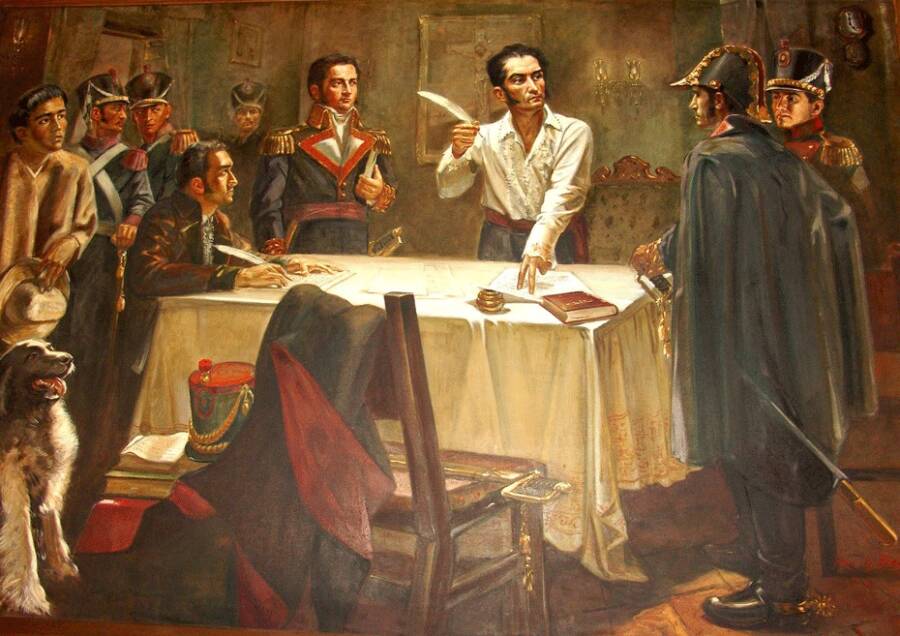

Wikimedia CommonsSimón Bolívar signs the Death War Decree.

In 1816, he returned to Venezuela, with support from the Haitian government, and launched a six-year campaign for independence. This time, the rules were different: All slaves would be liberated and all Spaniards would be killed.

Thus, Bolívar liberated enslaved people by destroying the social order. Tens of thousands were slaughtered and the economies of Venezuela and modern-day Colombia crumbled. But, in his eyes, it was all worth it. What mattered was that South America would be free from imperial rule.

He pushed on to Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia (which is named after him), and dreamt of uniting his newly liberated territory — essentially all of northern and western South America — as one massive country ruled by him. But, once again, the dream would never fully materialize.

On Aug. 7, 1819, Bolívar’s army descended the mountains and defeated a much larger, well-rested, and utterly surprised Spanish army. It was far from the final battle, but historians recognize Boyaca as the most essential victory, setting the stage for the future victories by Simón Bolívar or his subordinate generals at Carabobo, Pichincha, and Ayacucho that would finally drive the Spanish out of the Latin American western states.

Having reflected and learned from earlier political failures, Simón Bolívar began to piece together a government. Bolívar arranged for the election of the Congress of Angostura and was declared president. Then, through the Constitution of Cúcuta, Gran Colombia was established on Sept. 7, 1821.

Wikimedia CommonsA map of Gran Colombia.

Gran Colombia was a united South American state that included the territories of modern-day Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, parts of northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwestern Brazil.

Bolívar also sought to unify Peru and Bolivia, which was named after the great general, into Gran Colombia through the Confederation of the Andes. But after years of political infighting, including a failed attempt on his life, Simón Bolívar’s efforts to unify the continent under a single banner government collapsed.

On Jan. 30, 1830, Simón Bolívar made his last address as president of Gran Colombia in which he pled with his people to maintain the union:

“Colombians! Gather around the constitutional congress. It represents the wisdom of the nation, the legitimate hope of the people, and the final point of reunion of the patriots. Its sovereign decrees will determine our lives, the happiness of the Republic, and the glory of Colombia. If dire circumstances should cause you to abandon it, there will be no health for the country, and you will drown in the ocean of anarchy, leaving as your children’s legacy nothing but crime, blood, and death.”

Gran Colombia was dissolved later that year and replaced by the independent and separate republics of Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada. The self-governing states of South America, once a unified force under the leadership of Simón Bolívar, would be fraught with civil unrest through much of the 19th century. More than six rebellions would disrupt Bolívar’s home country of Venezuela.

As for Bolívar, the former general had planned to spend his last days in exile in Europe, but passed away before he could set sail. Simón Bolívar died of tuberculosis on Dec. 17, 1830, in the coastal city of Santa Marta in present-day Colombia. He was only 47 years old.

A Grand Legacy In Latin America

Wikimedia CommonsBolívar’s remains were eventually moved from Santa Marta, where he died, to a tomb in Caracas, where he was born.

Simón Bolívar is often referred to as the “George Washington of South America” because of the similarities the two great leaders shared. They were both rich, charismatic, and were key figures in the fight for freedom in the Americas.

But the two were very different.

“Unlike Washington, who suffered excruciating pain from rotten dentures,” says Cañizares-Esguerra, “Bolívar kept to his death a wholesome set of teeth.”

But more importantly, “Bolívar did not end his days revered and worshiped like Washington. Bolívar died on his way to self-imposed exile, despised by many.” He thought that a single, centralized, dictatorial government was what South America needed to survive independent from European powers — not the decentralized, democratic government of the United States. But it didn’t work.

Despite his notoriety, Bolívar did have a leg up on the U.S. in at least one respect: He freed South America’s slaves nearly 50 years before Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal” while owning dozens of slaves, whereas Bolívar set all of his slaves free.

Which is probably why Simón Bolívar’s legacy as El Libertador is heavily intertwined with the proud Latin identity and patriotism in countries across South America.

Now that you’ve learned the tale of Simón Bolívar, the patriotic liberator and leader of South America, read about Spanish King Charles II, who was so ugly due to family inbreeding that he even terrified his own wife. Then, learn about fearsome British Celtic leader Queen Boudica and her epic revenge against the Romans.