People have done some great — and ethnically questionable — things in the name of empire.

Early this month, three researchers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their discoveries on parasitic diseases. This December, the winners will receive their award at the official ceremony in Stockholm, where they will join the pantheon of scientific investigators whose discoveries changed countless lives for the better.

In the meantime, one historical medical milestone has a backstory worth knowing about: how the smallpox vaccine arrived in America.

An infectious disease just like those studied by the latest Nobel winners, smallpox was known in the 18th century as “the minister of death,” leaving countless casualties in its wake. It caused fever, aching, scabs filled with pus, and in many cases death. In fact, estimates suggest that in late 18th century Europe, just under half a million died each year due to the then-cureless illness.

Portrait of Edward Jenner, the discoverer of the smallpox vaccine.

Enter Edward Jenner. The year was 1796, and after hearing for years that some dairymaids were immune from smallpox after having contracted cowpox, the British doctor decided to investigate the matter for himself. After successfully inoculating a little boy with pus from a dairymaid’s cowpox lesion, Jenner introduced the smallpox vaccine. This was the beginning of a medical breakthrough.

Jenner’s innovation came at the right time. Spanish colonies in the so-called New World were being ravaged by the disease, which killed colonists in droves. When news of this epidemic hit the Spanish empire — made that much more personal when King Charles IV’s own daughter contracted the virus — one of histories most out of the ordinary immunization campaigns began.

Image Source: Wikimedia

In those days, the vaccine could only be transferred live since it wasn’t stored in vials and refrigerated. In other words, in order to administer the smallpox vaccine to a colonist, a living vaccine carrier had to be around. The Spanish crown faced a problem: how could the vaccine make its way across the ocean — and at minimal cost?

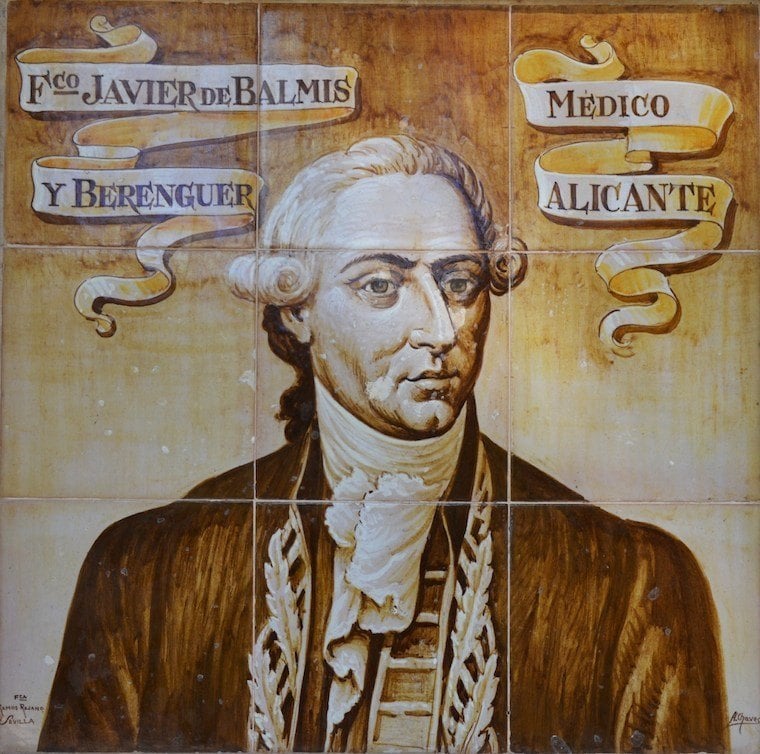

Xavier Balmis delivered an answer. A doctor of the king’s Royal Court, Balmis brought the vaccination overseas by using orphans as live vaccine carriers. While it might have not been the most orthodox way to transport the virus and therefore vaccination overseas, it worked.

A portrait of Xavier Balmis.

The process was very simple. While on the journey, which kicked off in 1803, Balmis would make a small incision into an orphan’s shoulder into which he applied the smallpox vaccine. Days later, an ulcer would develop on that child’s shoulder. Balmis and his crew would pop that vaccine-carrying lesion, and keep the vesicle fluid in paraffin-sealed glass slides for later use.

Balmis would then transfer the vaccine-wielding fluid to others by making similar incisions on two other children’s shoulders (Balmis infected two kids at a time to make sure the human chain was never broken).

The process would continue for the duration of the three-year voyage, with kids developing similar ulcers on their shoulders that carried the natural vaccine for a few days. The children were not of much use after the lesions dried, but they ensured that the vaccine sample would be alive when the expedition arrived to the Americas.

In what was later called the Balmis Expedition, the doctor took 22 boy orphans from ages 8-10 with him to the New World, landing in Puerto Rico, and then continuing to the continental mainland. Once in Venezuela, the expedition split and crossed the continent, with some heading as far north as San Francisco and others traveling as far south as Chile.

After crossing the Spanish territories in the New World – and sometimes buying children in order to continue the human vaccine-delivering convoy – Balmis crossed the Pacific Ocean and entered the Philippines and even China, where he was allowed to keep his vaccination program going.

Very little is known of the fates of the children with whom Balmis traveled, though local families are believed to have adopted some of them. What is known, however, is that this unorthodox enterprise likely saved hundreds of thousands of lives, and introduced vaccines to a global public.

Likewise, Balmis’ venture is considered by many to be the first international healthcare expedition — one not that dissimilar from the efforts of the World Health Organization, which was founded around 150 years after Balmis and his traveling band of orphans made their way to the Americas.

Of Balmis’ voyage, vaccine pioneer Jenner wrote, “I don’t imagine the annals of history furnish an example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as this.”