Built in just 60 days, Charles Lindbergh's "Spirit of St. Louis" was a custom-made aircraft designed for the sole purpose of getting the pilot from New York to Paris without stopping.

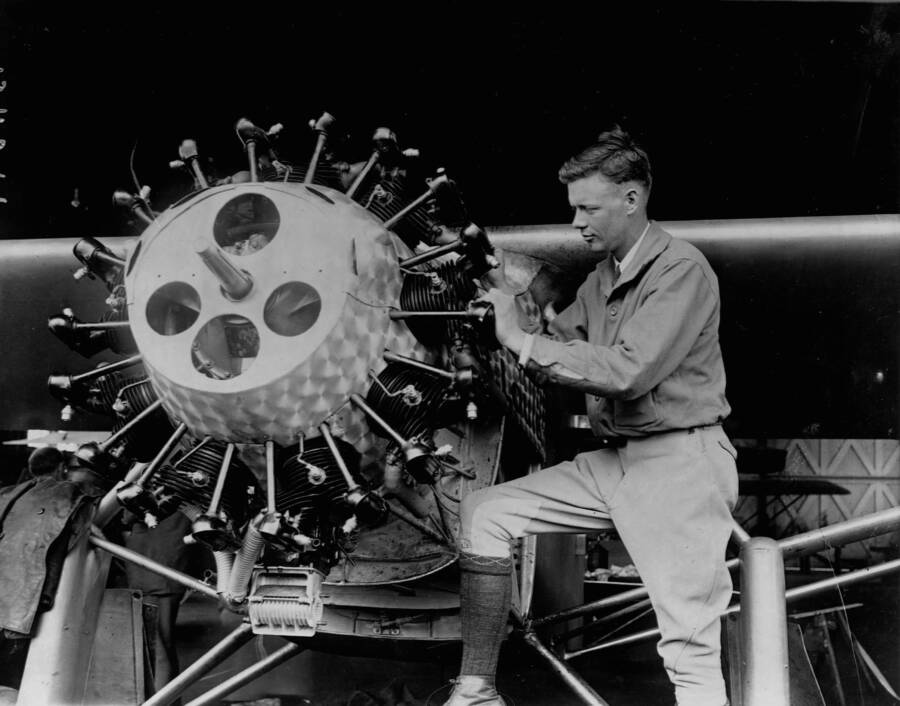

Library of CongressCharles Lindbergh stands in front of the Spirit of St. Louis on May 31, 1927.

On May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh hopped in the Spirit of St Louis at the Roosevelt Airfield in Garden City on Long Island and departed for Paris. Thirty-three hours later, he arrived in the City of Light, marking the first time in history anyone had made the transatlantic flight non-stop.

The Spirit of St. Louis is a shockingly rudimentary plane by today’s standards. Shorter than a school bus, it’s made from treated canvas, steel, and wood with a single wicker seat. And it has no forward sightlines from the cockpit, meaning Lindbergh had to fly based on instruments alone.

Yet Lindbergh succeeded where others failed. And for his efforts, Lindbergh took home $25,000 in the prestigious Orteig Prize (over $400,000 in today’s money) and landed in the annals of history. He achieved almost overnight celebrity, and the Spirit of St Louis became the best-known aircraft in the world.

How The ‘Spirit Of St Louis’ Was Made

Smithsonian InstitutionThe cockpit of the Spirit of St. Louis. The plane had been so heavily modified that the only way to look forward was through a periscope on the left side of the instrument panel.

For all of its accomplishments, it’s amazing to think that the Spirit of St Louis is little more than a single-engine monopropeller plane made with a canvas-covered steel frame. And the wings use no metal but are instead canvas over wood for the entire 46-foot span.

Weighing in at 2,150 pounds without fuel, the plane stood just under 10 feet tall and was just under 28 feet long. And the canvas used to cover it was known as airplane fabric, a common material for the time, and coated in a paint called “airplane dope” that helped create a body resistant to all the elements.

Its engine was mighty for its time but relatively paltry by today’s standards. The Wright J-5C “Whirlwind” engine, which was said to allow the plane to perform for more than 9,000 hours, only had a 220 horsepower engine — the same type of engine found in a 2021 Audi TT convertible sports car. By comparison, today’s Boeing 777 has nearly 15,000 horsepower in both of its engines.

Nevertheless, the Spirit of St Louis was an engineering marvel in the early 20th century — so much so that in February 1927, the Ryan Airlines Corporation of San Diego, California agreed to build the engineering marvel at a cost of $6,000, excluding the engine.

Its original template was the Ryan M2. But, per Lindbergh’s specifications, the customized plane had to have fuel tanks where the passengers would be so that Lindbergh could get from New York to Paris without stopping.

In turn, the wingspan also had to be increased to accommodate the extra weight that the fuel brought on. Then due to the longer wingspan, the whole plane had to be elongated, meaning that throughout his flight, Lindbergh would have to keep his hands on the joystick and feet on the pedals to prevent them from shaking.

Charles Lindbergh’s Famous Transatlantic Flight

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty ImagesCharles Lindbergh examines the engine cylinders on the Spirit of St. Louis shortly before his historic flight in 1927.

Before the Spirit of St Louis took flight, other enterprising pilots had tried to make the historic non-stop journey from New York to Paris. Shortly before Lindbergh took to the skies, Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli departed from France for New York. Unfortunately, shortly after they passed over Ireland, they were never seen again.

That brought hope to Lindbergh, who got backing for the inaugural flight from Harold Bixby, the president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce. Lindbergh, who had adopted St. Louis as his home, had a reputation for being a hotshot pilot in the area, and Bixby was convinced that he’d be able to position St. Louis as an aviation hub if Lindbergh was able to pull off this impossible feat.

On May 12, 1927, Lindbergh and his infamous plane landed at Curtiss Field in Long Island, New York, ready to take the historic transatlantic flight. Eight days later, the Spirit of St Louis taxied to the neighboring Roosevelt field, which had a longer runway. And at 7:52 a.m., Charles Lindbergh took off, heading straight towards Paris.

Over the next 33 and a half hours, Lindbergh fought sleep deprivation, fog, and icing. He also had to repair a torn oil line mid-flight and, at one point, dropped his pliers under the pedals. But at 10:22 p.m. local time, the Spirit of St Louis landed at Aéroport Le Bourget, having flown a total of 3,600 miles.

The ‘Spirit Of St. Louis’ At The Smithsonian

Eric Long/Smithsonian National Air and Space MuseumThe Spirit of St. Louis has been on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., since 1927.

When Lindbergh landed, he was greeted by more than 150,000 cheering people and a check for $25,000, presented to him by New York City hotelier Raymond Orteig, who created the Orteig Prize for the first person to make a successful transatlantic flight from Paris to New York (or vice versa).

And the bet made by the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce was the correct one. Overnight, Lindbergh went from a local hotshot pilot to an international celebrity, receiving a Medal of Honor and a Distinguished Flying Cross from President Calvin Coolidge. That year, he was honored as Time Magazine‘s first-ever “Man of the Year.”

After Lindbergh completed the flight, the Spirit of St Louis was transported back to the United States via a freighter ship. But that wouldn’t be the last time it would take flight. For the next ten months, Lindbergh flew the plane extensively over North, Central, and South America to promote the growing aeronautics industry.

Finally, Lindbergh piloted the Spirit of St Louis for the last time on April 28, 1927, when he flew the aircraft from St. Louis to Bolling Field in Washington, D.C. From there, he donated it to the Smithsonian Institution, where it has remained ever since as one of the museum’s most popular exhibits.

At the time of its retirement, it had flown nearly 500 hours and made nearly 200 flights.

After learning about the Spirit of St Louis, read about Charles Lindbergh’s involvement with the original “America First” movement. Then, see how these 12 famous explorers changed the face of the world.