Lucky hats, doping, biased referees and more — all these seemingly strange actions can be explained by psychology.

There’s no denying that psychology is a huge part of sports. Indeed, it sometimes seems as though athletes, spectators, and even referees are just pawns in a giant psychological experiment. Here are nine common actions from players and fans alike that, although odd on the face of it, actually have a legitimate explanation from sports psychology.

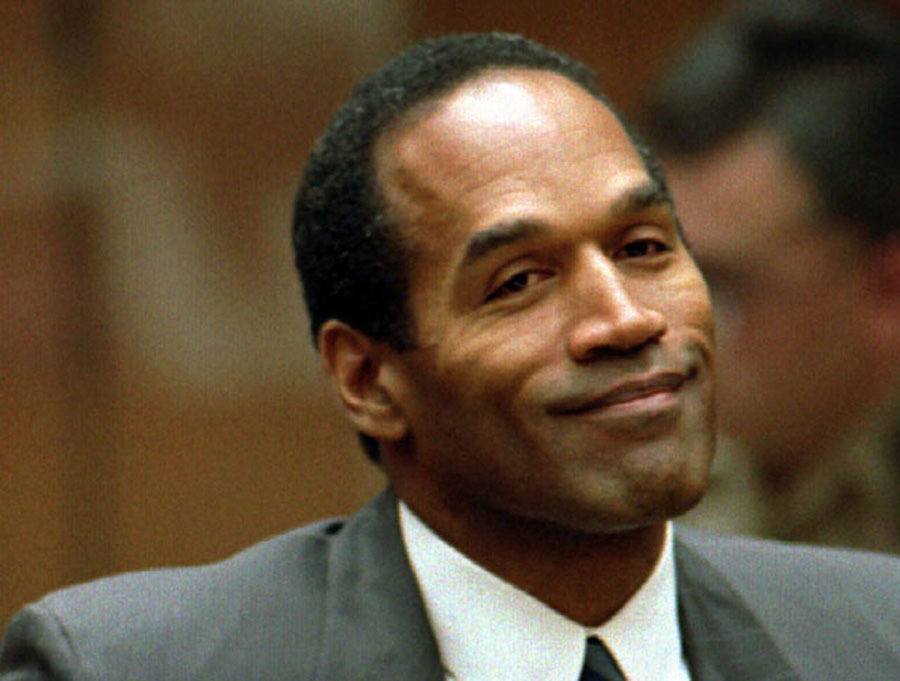

1. Why you can’t ditch that lucky baseball cap

Image Source: Wikipedia (en)

In sports, psychologist B.F. Skinner’s operative conditioning has its own name – superstitious conditioning. It sounds fancy, but the term can be seen in action any time an enthusiastic sports fan insists on wearing their “lucky” hat for a game, refuses to wash a jersey after it’s been worn during a win, and so on.

However misguided, the thinking behind such actions is dictated by a past event, wherein the clothing item is associated with a particularly consequential outcome such as winning or losing a game.

This won’t sound flattering to sports fans, but Skinner originally developed his theory while working with birds. When training his pigeons, the behavioral psychologist noticed that the birds often added in an extra, accidental step — such as spinning in a circle — before pulling the treat lever.

They did this, Skinner postulated, because spinning composed part of one sequence that yielded a treat. Thus the birds assumed it a necessary step to receiving future treats. Not understanding the spinning wasn’t actually needed for a treat pellet (or to put it in a more human perspective, a game win), the pigeons re-enacted the pointless ritual over and over again.

2. Why you identify yourself as part of the team (and why that makes perfect sense)

Image Source: Pixabay

Have you ever wondered why it is that sports fans start saying “we” when referring to a given team’s performance? Sometimes it’s due to the team’s location, other times it’s due to an affinity for a certain player. Whatever the reason, the bottom line is that once fans strongly identify with a particular team, the team becomes an extension of the fan.

This is a literal confusion in the brain that denies the difference between “me” and “the team,” according to Eric Simons, author of The Secret Lives of Sports Fans: The Science of Sports Obsession. “Once you’re bonded to a team, and you experience all the benefits that come from it, then the relationship actually makes a lot of sense,” Simon said. “It’s quite rational to keep that relationship.”

Coupled with the sense of community that this attachment fosters, it also makes some sense that sports fans are said to be less depressed and have a higher self-esteem than non-sports fans. A 2013 study published in Psychological Science even showed that fans ate healthier after a win. Even when a team performs poorly, there is a kind of camaraderie in shared misery.

Although all of this sounds positive, studies have also suggested that this “we” business has resulted in instances of heart attacks, careless driving, and domestic disputes following negative outcomes of sporting events.

3. Why it’s natural to really, really hate the opposition

Explaining the dark side of camaraderie is the “ingroup-outgroup bias” phenomenon, which explains the hatred sports fans have of “others,” even when the dividing line is arbitrary.

There are now numerous studies on this kind of bias, but the most famous one was conducted in a schoolroom in 1968. An Iowa schoolteacher named Jane Elliot divided up her third grade class on the basis of eye color, and immediately implied the blue-eyed children were the “better” group. Blue-eyed children began shunning the brown-eyed group immediately and relentlessly.

The tables were then turned, and the purportedly better brown-eyed kids turned on their blue-eyed classmates and doled out the same social punishments. This very well may be an unconscious survival mechanism, but it’s exploited by the sports world, where teams financially benefit from rivalries.

4. Why the “home field advantage” may not be such an advantage after all

Athletes are not immune to psychological effects, either — take the perceived “home field advantage,” for example. The term describes the perceived benefits wherein a team, by playing at “home,” avoids the tiring nuisance of travel, is familiar with the field, and typically has more fans in the stands cheering them on.

These perceived benefits do come with their own costs, which Florida State psychologist Roy Baumeister describes in the “home choke hypothesis.” Essentially, this suggests that a team playing at home in a playoff situation is actually at a disadvantage because they are more self-conscious and thus unable to focus on the game at hand.

The hypothesis goes on to say that the perceived advantage may lead to overconfidence and thus carelessness, with the result that the team may crumble when they find themselves losing, stunned that they couldn’t make this “advantage” work in their favor.

5. Why we all have such a strong, innate desire to win

Photo: Korea.net / Korean Culture and Information Service Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

To say that “winning isn’t everything” could actually be a lie. Indeed, Trinity College psychology professor Ian Robertson says that it’s “probably the single most important thing in shaping people’s lives.”

In his book The Winner Effect, Robertson explores the immense drive we possess to win, and it seems to be rooted deep within us at a biological level. “Winning increases testosterone, which in turn increases the chemical messenger dopamine, and that dopamine hits the reward network in the brain, which makes us feel better,” Robertson said.

There’s really no substitute for winning – not even being second best. Neuroscientist Scott Huettel highlights this in his observations of Olympic medalists: in photos taken of the athletes on the podium, the silver medalist often looks vexed, where the gold and bronze winners look quite pleased.

“The bronze medalists had thoughts that compared themselves to everybody else, so they thought, ‘Wow, if I’d only done a little worse, I would be one of those many people that’s not here on the medal stand — I made it, I’m a medalist!'” said Huettel. “The silver medalists, though, had thoughts that compared themselves to the gold medalist — I just missed it!'”

6. Why winners are more likely to cheat than losers

Photo: Charles LeBlanc Image Source: Flickr

Say you’ve just won some sort of competition. You have no reason to cheat, right? Not so, say researchers at Ben-Gurion University. In tests, competition winners behaved more dishonestly when compared to losers in a subsequent and unrelated task – one which asked them to steal from their counterparts.

What’s the explanation for this strange behavior? Researchers say it has to do with a sense of entitlement that comes after beating a competitor, which can often result in unethical behavior. “These findings suggest that the way in which people measure success affects their honesty,” said Dr. Amos Schurr from BG University.

“When success is measured by social comparison, as is the case when winning a competition, dishonesty increases,” he continued. “When success does not involve social comparison, as is the case when meeting a set goal, defined standard or recalling a personal achievement, dishonesty decreases.”

7. Why some athletes resort to doping

Photo: Wladyslaw Image Source: Wikipedia (en)

Speaking of honesty and transparency, what makes some athletes prone to doping, while others resist? Is it just a matter of how strong one’s moral compass is? Not according to some studies. A 1995 survey of top-tier athletes suggests that “195 out of 198 admitted they would take performance enhancing drugs if they would win and not be caught.”

This figure might have to do with the fact that cheating is somewhat contagious: According to behavioral economist Dan Ariely, people are more drawn to cheat when they feel they can’t be caught, and especially if they see someone else cheating and getting away with it.

There are numerous reasons to steer clear of performance enhancing drugs besides their questionable morality; health risks abound with most methods and substances. Even so, over half of the athletes in the aforementioned survey claimed they would put their very lives at risk if it meant they could have five years of success in their sport. This says more about the power of our drive to win than anything else ever could.

8. Why some athletes play through injuries — even when it’s against their best interests

Image Source: Pixabay

Dealing with a debilitating injury has profound effects on the life of an athlete. Psychological issues can easily arise from physical injuries, most notably in how the athlete perceives themselves after being sidelined.

“When athletes have strong identity ties to their physical activity,” says sport psychology counselor Jim Gavin, “They are thrown into a state of shock or disorientation [when an injury occurs].”

Somewhere along the line, athletes are usually taught the difference between “good and bad pain,” learning to differentiate the general soreness from a workout from that of a serious injury. But the fear of being shut-down and thus being stripped of their identity makes some athletes deny even the most painful of injuries, increasing the likelihood of severe problems in the long run.

9. Why referees make biased decisions

Image Source: Pixabay

We’ve all been there: the referee in a given game is showing clear bias against our team. Some may shrug this off as away-team speculation, but it has been shown that referees tend to give harsher fouls to the visiting rivals. Most referees, regardless of experience level, will unconsciously take cues from the crowd – and the home team always reacts strongly to the fouls committed against them.

“The evidence is overwhelming,” says professor Alan Nevill, a biostatistics specialist at the UK’s Wolverhampton University. “And it is across a range of sports including football.”

Nevill conducted a study that included 40 referees who judged a total of 47 pre-recorded plays. A control group observed the plays in silence, and the other group observed the plays with crowd noise. Referees in the control group called significantly fewer fouls against the home team than the referees with noise – over 15% less.

To combat this, it’s been suggested that referee training include instruction on how to tune out distractions like crowd noise. Given the realities of the field, unconscious bias is likely to exist with or without that training — and maybe, some say, that’s not so terrible.

Said David Forrest, professor of economics at Salford University, about the matter: “Statisticians think justice is everything. But randomness and noise create uncertainty of outcome, which is one of the appeals of sport.”