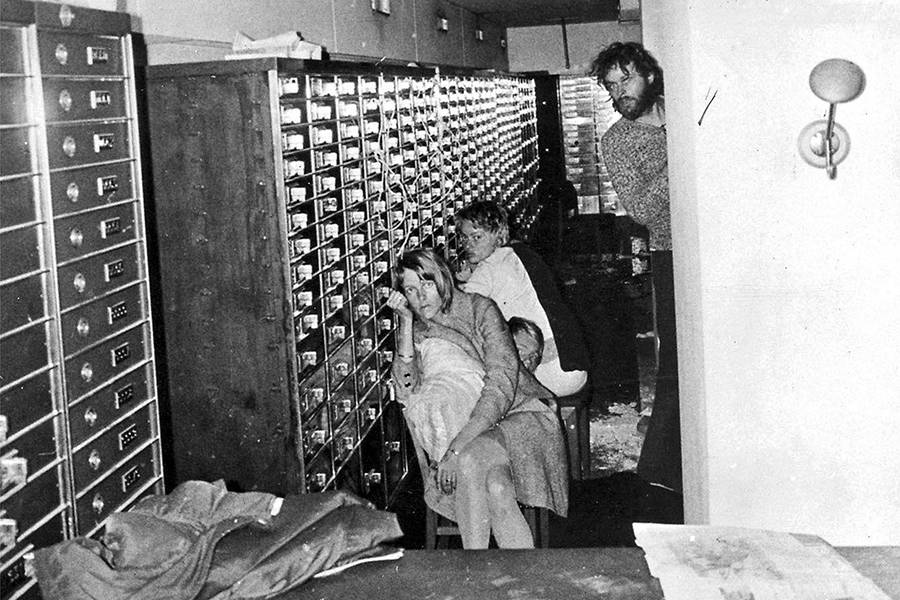

The first victims of Stockholm syndrome found the symptoms as unexplainable as the doctors who examined them.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Kreditbanken building, where Jan-Erik Olsson took his hostages.

In 1973, Swedish criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot coined a most interesting psychiatric phenomenon. He called it Norrmalmstorgssyndromet, after Norrmalmstorg, the area of Stockholm where the phenomenon had originated. To people outside of Sweden, however, it became known as “Stockholm syndrome.”

The case for his newfound condition was a curious one. A bank robbery had occurred, and hostages had been taken. However, unlike every hostage situation before it, the hostages felt no fear toward their hostage takers. In fact, it was quite the contrary. The hostages actually seemed to have developed positive feelings toward their captors, baffling almost every law enforcement agent and psychiatric practitioner in the world.

On the morning of Aug. 23, 1973, Jan-Erik Olsson, on leave from prison, walked into the Sveriges Kreditbanken at Norrmalmstorg, a bank in central Stockholm. Armed with a submachine gun, Olsson fired several shots at the ceiling and announced he was robbing the bank.

As he fired, he cried out “The party has just begun!”

Upon Olsson’s arrival, one of the bank workers had triggered a silent alarm, and two policemen showed up and attempted to subdue Olsson. He fired at one of the policemen, hitting him in the hand. The other he forced into a chair, and told to “sing something.” As the unharmed policeman sang out “Lonesome Cowboy,” Olsson collected four bank workers and ushered them into a vault.

In return for the prisoners, Olsson told the police, he wanted a few things in exchange. First, he wanted his friend, fellow prisoner Clark Olofsson to be brought to the bank. Then, he wanted three million Swedish kronor (roughly $376,000), two guns, bulletproof vests, helmets, and a fast car.

AFP PHOTO / PRESSENS BILD FILES / ROLAND JANSSON / AFP PHOTO / SCANPIX SWEDEN / ROLAND JANSSONPress photographers and police snipers lie side by side on a roof opposite the Kreditbanken bank on Norrmalmstorg

The government allowed Olofsson to be released, to serve as a communication link between police and Olsson, and within a few hours he arrived at the bank with the ransom, the requests, and a blue Ford Mustang with a full tank. The governments only request for Olofsson and Olsson was that they leave the hostages behind when they left.

Unfortunately, the duo didn’t like these terms, as they wanted to leave with the hostages in order to assure their own safe passage out of the bank. In a rage, Olsson called the Swedish Prime Minister, threatening the life of one of the hostages, a young woman named Kristin Enmark.

The world watched in horror through the dozens of news crews camped out outside the bank. The public flooded local news and police stations with suggestions as to how to get the hostages out, which ranged from hostile to downright ridiculous.

However, while the public outside the bank grew more opinionated and worried by the day, inside the bank something very strange was happening.

AFP/Getty Images Clark Olofsson and two of the hostages.

The first sign that something was amiss came the day after Olsson’s threatening call. The Prime Minister received another call from the group inside the bank, though this time it was from one of the hostages – Kristin Enmark.

To the Minister’s surprise, Enmark did not express her fear. Instead, she told him how disappointed she was with his attitude toward Olsson, and would he mind letting them all go free.

It seemed that while the outside world was worried the hostages would be killed, the hostages had instead formed a relationship with their captors, and had begun to bond with them. Olsson had given Enmark a jacket when she was cold, had soothed her during a nightmare, and had let her take a bullet from his gun as a keepsake.

Another hostage, Birgitta Lundblad, had been allowed to call her family, and when she couldn’t reach them, was encouraged to keep trying and not give up. When another hostage, Elisabeth Oldgren, complained of claustrophobia, she was allowed to take a walk around the outside of the vault (albeit while tied to a 30-foot leash).

“I remember thinking he was very kind to allow me to leave the vault,” she told the New Yorker a year later.

Her fellow hostage Sven Safstrom, the lone male hostage, agreed with her, despite the fact that Olsson threatened to shoot him in the leg.

“How kind I thought he was for saying it was just my leg he would shoot,” he remembered.

“When he treated us well, we could think of him as an emergency God,” he continued.

AFP PHOTO PRESSENS BILD / AFP PHOTO / SCANPIX SWEDEN / EGAN-Polisen Jan-Erik Olsson is lead out of the bank after the tear gas was released.

Eventually, six days after Olsson had first entered the bank, the police outside reached a decision. Due to the hostage’s confusing pleas for mercy on their captors, there seemed no way to get them out other than by force. On Aug. 28, police pumped tear gas into the vault for a small hole in the ceiling. Olsson and Olofsson surrendered almost immediately.

However, when the police called for the hostages to come out first, their irrational allegiance to their captors held fast. They insisted that the captors leave first, as they believed the police would shoot them if they were the last in the vault. Even as the captors were taken into custody and carried off, the hostages defended them.

The unexplainable empathy that the captives felt for their captors, their “Stockholm syndrome,” confused police and health professionals in the months after the event. The day after being released, hostage Elisabeth Oldgren admitted she didn’t even know why she felt the way she did.

“Is there something wrong with me?” she asked her psychiatrist. “Why don’t I hate them?”

Before long, the term Stockholm syndrome would be used to describe the situation and others in which the hostage became emotionally attached to their captors. Stockholm syndrome again was brought to national attention a year after the bank robbery, when American newspaper heiress Patty Hearst claimed it explained her allegiance to the Symbionese Liberation Army, an urban guerrilla group that had kidnapped her.

For the original victims, it appeared that their Stockholm syndrome lingered. After Olofsson and Olsson were imprisoned, the hostages made routine jailhouse visits to their captors, never finding themselves able to break the inconceivable bond that had formed under such dark circumstances.

Next, read about the world’s biggest crime organizations. Then, learn the origins of these ten popular slang words.