Throughout much of 20th century Spain, a criminal network of doctors and nuns stole anywhere from 40,000 to 300,000 babies from their mothers at birth, constituting one of the most horrific yet least known events of the Franco dictatorship.

Picture taken during the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s of General Franco (C) with Chief of Staff Barroso (L) and Commander Carmenlo Medrano looking at a map. Image Source: STF/AFP/Getty Images

General Francisco Franco came to power in 1939, after winning a civil war that had bathed the country in blood for three years. In the four decades that followed — and up to his death in 1975 — Spain stayed mostly closed to the outside world, delaying industrial progress and punishing those who fought on the losing side of the conflict.

It was during those years when it is believed that tens of thousands of infants born to “undesirable” families started disappearing from their mothers’ hands.

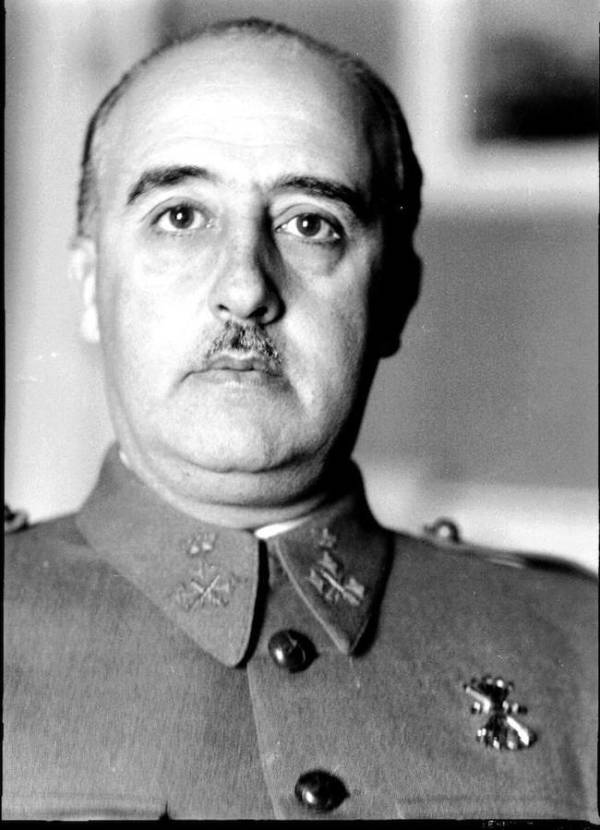

The Spanish dictator from 1939 to 1975, Francisco Franco.

According to the BBC, the practice may have originally been borne from Francoist ideology which promoted the domination of the “pure” right wing over “inferior” left wing families, but over the years it changed, “as babies began to be taken from parents considered morally — or economically — deficient.”

Following the requests of families who could not have children, a corrupt web of nuns, priests, doctors and nurses went to great lengths to steal babies — most of whom came from low-income families or single mothers — on their behalf or provide them with illegal adoptions.

To cover up the job, baby-seeking families were sometimes told to fake a pregnancy; other times the families simply believed they were going through a legal adoption channel, paying the doctors and nuns for their services.

The latter was easy to do, as up until 1987 adoptions in Spain were done through hospitals, which were largely under the influence of the Catholic Church, the BBC wrote.

How Did This Form Of Human Trafficking Work?

Protestors march in the streets of San Sebastián, demanding justice for the stolen babies. Source: Flickr

As with any hospital, some women did not want to keep their newborns and offered them up for adoption. Others were convinced by clinic staff to give them up for adoption. The women did not receive any financial support in exchange for giving up their newborns, and in many cases nurses and doctors forged paperwork to make it appear as if the adopting parents were the biological ones.

Worse still, some women gave birth wanting to keep their child and, after the fact, were falsely told that their children had died.

Mothers were denied access to their deceased child’s body, with some saying they were shown a newborn corpse which nurses and doctors claimed belonged to them. The clinic, these mothers were often told, would take care of the burial. This trafficking continued all the way up until the ’90s, the BBC wrote.

Since police inquiries began in 2011, a handful of former clinic workers have come forward as eyewitnesses. They confirmed that the mothers would be given a certain dose of anesthesia so they would be in a state of confusion during the birth and could therefore be more easily tricked into believing the baby had died. Graves supposedly containing the remains of these infants have been opened since investigations began, and have revealed only the bones of adults or animals — sometimes just a handful of stones.

Although these illegal practices happened to mothers all over Spain, some names came up in cases more than others — namely a doctor named Eduardo Vela and a nun, Sister María Gomez, who worked within Madrid’s San Román maternity ward.

Why Investigations Started

A meeting in 2012 with the then-Minister of Justice, Minister of Interior, Minister of Health and General Attorney to address the stolen babies crisis. Source: Flickr

In 2011, a dying man in Catalonia told his “son,” Juan Luis Moreno, that he and one of his close friends, Antonio Barroso, had been bought as infants. As Moreno recounted, “He said, ‘I bought you from a priest in Zaragoza’. He said that Antonio had been bought as well.” The childhood friends then consulted an adoption lawyer, who said he “came across cases like theirs all the time,” the BBC wrote.

Moreno’s adoptive father also told him that the summer vacations Moreno and Barroso’s families would take to the town of Zaragoza were not just for holidays, but to visit a nun and pay an installment of the illegal adoption fee, CNN reported.

The duo tracked down and confronted the nun — who initially claimed not to know what they meant — telling CNN they felt “like…chickens in the market” or “two kilos of tomatoes.”

When Moreno and Barroso brought their story to the media, hundreds of other adults who had either been told they were adopted or had always suspected they might not be the biological children of their parents started digging into their own pasts. But it was hard to find the truth: Many births were never registered, documents had been forged, and again, some families truly believed they were legally adopting a baby.

What Has Come Of The Investigations?

Spanish nun Maria Gomez Valbuena leaves a court in Madrid after refusing to testify before the judge for her alleged involvement in a case of stolen children. Image Source: Getty Images/Pedro Arrester

To date, more than a thousand cases have been brought to the courts, with little resolution.

Gomez, one of the most commonly-cited names among victims who have come forward, appeared in a Spanish court in April 2012, accused of snatching and selling a child in 1982. She refused to testify, and a day later released a statement calling the accusations “disgusting” and saying she had never heard of “a single case of a newborn being taken from a mother through coercion or threats,” CNN wrote. Gomez died a year later, taking her secrets with her.

When a BBC reporter confronted Dr. Vela — another regularly occurring name in stolen baby cases — during a medical appointment, the doctor replied, “I have always acted in [God’s] name. Always for the good of the children and to protect the mothers. Enough.”

Victims’ associations, some started by Moreno and Barroso, have attempted to match DNA from adults who suspect that they were stolen at birth and from mothers who never believed their children had died, but have run into problems since data protection laws keep DNA banks from sharing or cross-referencing data, the BBC wrote.

These groups have thus requested the government create a centralized DNA bank to make it easier for victims to find their loved ones, to no avail. The Spanish government has yet to address their request for a DNA bank, and although a public prosecutor has investigated the case and has brought in some suspects to testify, no one has been convicted of a crime.

More than 60 years have elapsed since some of these babies were snatched from their mothers, meaning that many of the victims — parents and children — are no longer alive. But one has to wonder if living with so many unanswerable questions about who you are and who you might have been is even worse.