A new study on the cache of unique stone balls uncovered at Qesem Cave has unraveled the puzzle which has long bewildered archaeologists.

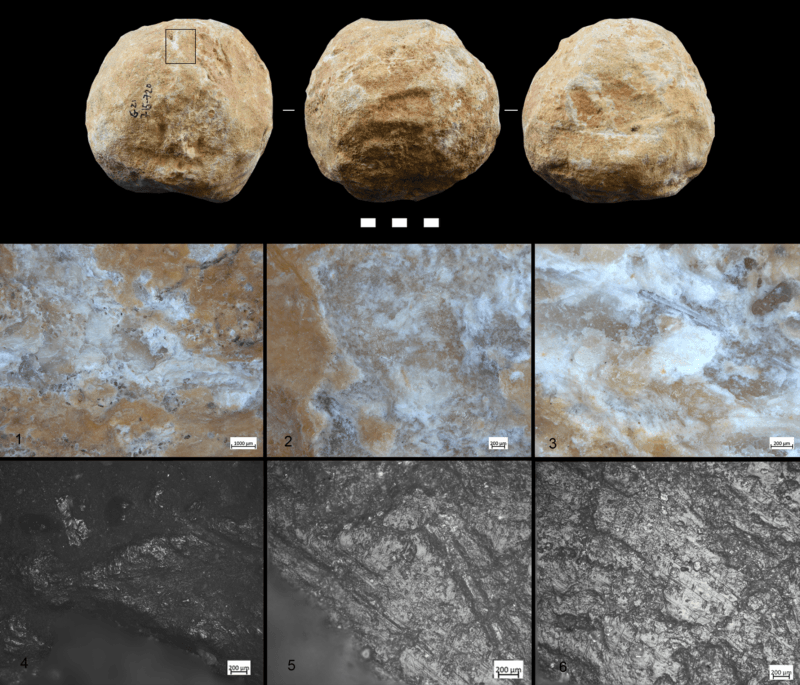

Assaf et al.A mysterious haul of stone balls was uncovered in the Qesem Cave archaeological site in Israel.

For the longest time, archaeologists were stumped over the use of simplistic prehistoric tools found in caves around the world: stone balls.

Researchers have uncovered these mysterious tools dating back to 2 million years ago inside caves in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Clearly, these artifacts had been used by our ancestors — but for what exactly researchers could not figure out until now.

A team of international scientists studied a unique cache of 30 stone balls that were uncovered in Israel’s Qesem Cave where humans lived between 200,000 to 400,000 years ago. They determined that the stone balls functioned as tools to break open thick animal bones so humans could access the marrow.

The new study was published in the journal PLOS One in early April 2020.

According to Live Science, a team of researchers led by Ella Assaf, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near East Cultures at Tel Aviv University, finally cracked the mystery behind the stone balls.

Assaf et alScientists conducted two separate experiments using naturally-shaped stones and stones shaped into round balls.

Assaf’s team found that 29 of the 30 stone balls were made of limestone or dolomite rock. The balls were not perfectly round and had ridges from being used to chip away at something.

The team examined the peculiar stone balls more closely under a microscope and discovered wear marks and organic residues which indicated that the stones had been used like can openers on animal bones so that the cave inhabitants could extract the marrow from the bones.

Assaf and her team conducted two different experiments to further strengthen the theory behind their findings. In the first experiment, the researchers used cobblestones which are naturally rounded stones that measure larger than pebbles to break apart large animal bones.

In the second experiment, they switched to using stones that they had shaped into round balls which were used to break the animal bones, too.

The researchers found that the shaped stone balls were much more efficient in breaking the bones than the stones that had their natural shape.

“These tools provide comfortable grip, they don’t tend to break easily, and you can rotate them and use them repetitively since they have multiple ridges,” Assaf said. “These high ridges help to break the bone in a ‘clean’ way, and you can extract the marrow relatively easily.”

Further evidence substantiated the study’s findings, like the wear marks that were left on the bones during the experiments. The modern replicas of the stone balls made by the team left markings that were similar to the ones that they had analyzed on the original stone balls.

Assaf et alResearchers analyzed traces of markings on the stone balls using a microscope.

“As bone marrow played a central role in human nutrition in the Lower Paleolithic, and our experimental results show that the morphology and characteristics of shaped stone ball replicas are well-suited for the extraction of bone marrow, we suggest that these features might have been the reason for their collection and use at Qesem Cave,” the study’s authors wrote.

With that, a long-standing mystery of the archaeological world was finally answered.

“Our study provided evidence, for the first time, regarding the function of these enigmatic-shaped stone balls that were produced by humans for almost 2 million years,” Assaf said.

More remarkable is the fact that these stone balls were likely brought by the Qesem Cave dwellers from somewhere else, kind of like shopping for secondhand tools, a habit of this population that has been documented in prior studies.

The stone balls are coated with a shiny top layer that naturally developed due to exposure to the elements. But the topcoat on the stone balls is different than that found on the other tools in the cave which suggests the stone balls came from a different environment.

“The Qesem people specifically selected these ancient, ready-made tools that somebody knapped before them [perhaps from older sites], probably due to their specific round morphology,” Assaf said. “It wasn’t a random choice — they brought them to the cave especially for bone-breaking activities.”

Compared to the more modern stone tools found in the Qesem Cave, the cache of stone balls possibly represents the last batch of “old technology” that was found in the Levant, the territory right on the east of the Mediterranean.

Next, learn about the 78,000-year-old artifacts that changed how we view the Stone Age and check out the facial reconstruction of ancient skulls that reveals what humans looked like 9,500 years ago.