The Sullivan brothers enlisted in the Navy on the condition that they be kept together — then all five siblings were killed in action when the USS Juneau was destroyed by the Japanese on November 13, 1942.

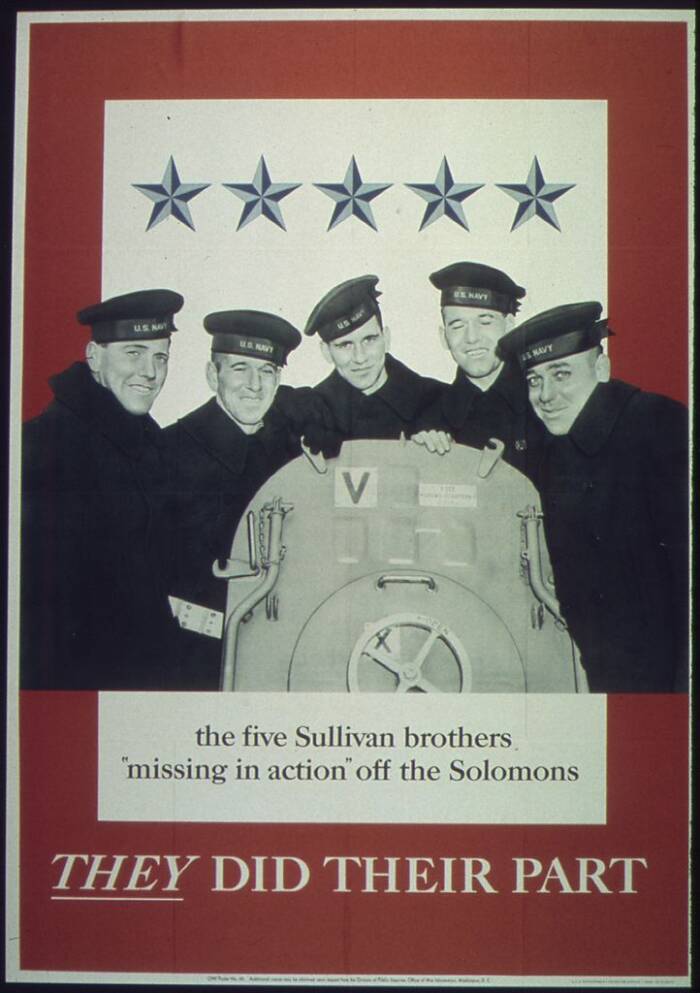

Public DomainThe five Sullivan brothers — Joe, Frank, Al, Matt, and George — at the commissioning of the USS Juneau.

On a cold winter morning in 1943, Thomas Sullivan was getting ready for work in Waterloo, Iowa, when he heard a knock on the door. Glancing out the window, Thomas saw the blue and gold uniform of Naval officers. He knew with chilling certainty that the officers were there to tell him that one of his sons had been killed while serving during World War II. But as they informed Thomas, not one, but all five Sullivan brothers had perished.

The Sullivan brothers — Joe, Frank, Al, Matt, and George — had decided to enlist in the Navy after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which had killed one of their friends. Though U.S. Navy policy discouraged siblings from serving together, the Sullivan brothers insisted they be stationed on the same ship — and were granted their request.

Tragically, all five brothers were aboard the USS Juneau during the Battle of Guadalcanal when their ship was struck by a Japanese torpedo. Three of the Sullivan brothers died instantly; the two others perished shortly afterward.

Their story captured the attention of the nation and became a “rallying point” for the war effort. Even today, the Sullivan brothers are lauded as all-American heroes.

The Sullivan Brothers Decide To Enlist After Pearl Harbor

The Sullivan brothers were born into a family of seven children in Waterloo, Idaho. George Thomas Sullivan was born on Dec. 14, 1914; Francis Henry “Frank” Sullivan was born on Feb. 18, 1916; Joseph Eugene “Joe” Sullivan was born on Aug. 28, 1918; Madison Abel “Matt” Sullivan was born on Nov. 8, 1919; and Albert Leo “Al” Sullivan was born on July 8, 1922. They also had a sister, Genevieve, and another sister who died in infancy.

The lives of the Sullivan brothers abruptly changed on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor during World War II. The attack was horrifying for many Americans, but for the Sullivans, it was personal. Their friend William Ball had been aboard the USS Arizona during the attack and had been killed.

U.S. Navy/Naval History & Heritage CommandThe destruction of the USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The brothers decided to enlist in the Navy.

For the two oldest brothers, George and Frank Sullivan, it was a re-enlistment. They had both served on the USS Hovey until 1941, when they were honorably discharged. And on Jan. 3, 1942, they went to Des Moines with their brothers to sign back up.

They were determined not only to fight, but to fight together. Though the Navy hesitated to allow five brothers to serve on the same ship — it was against Navy policy — the Sullivan brothers insisted. According to Irish Central, George even wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy to make their case, arguing that he and Francis had already served and that the brothers wanted to “stick together.” He wrote: “We will make a team together that can’t be beaten.”

The Navy ultimately agreed to let the Sullivan brothers serve on the same ship. The siblings trained together at the Naval Training School in Great Lakes, Illinois, and were then assigned to the USS Juneau in February 1942.

Naval History & Heritage CommandThe USS Juneau in 1942.

Sadly, all five Sullivan brothers would be killed just nine months later.

The Sinking Of The USS Juneau That Killed The Sullivans

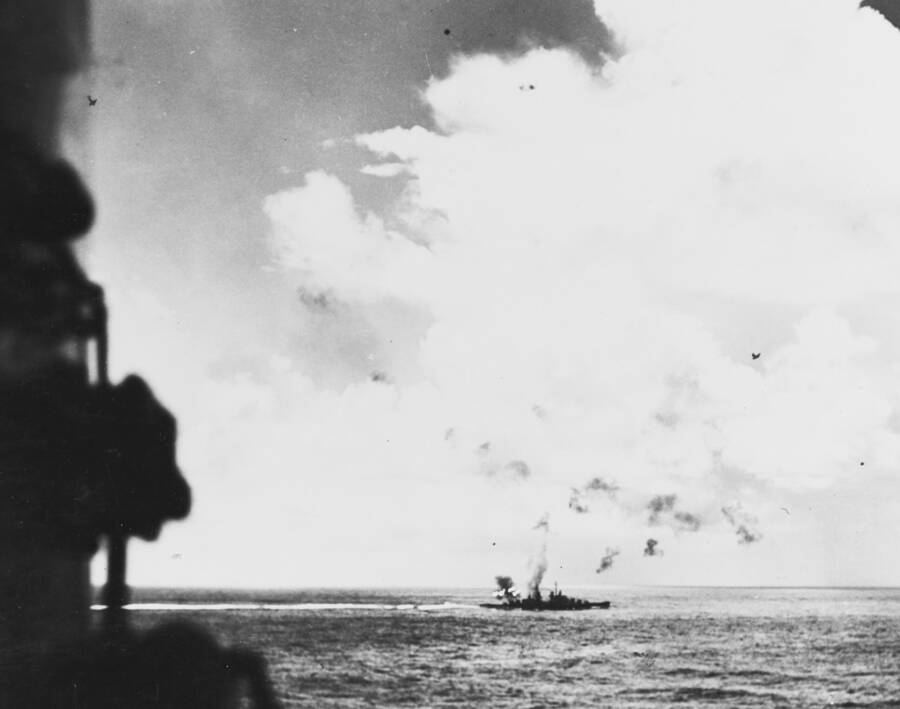

U.S. NavyThe USS Juneau engaging with Japanese aircraft during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. Oct. 26, 1942.

The USS Juneau originally served in the Atlantic Ocean, but was sent to the Pacific Ocean in August 1942. A few months later, it engaged in the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands on Nov. 12.

At around midnight, the USS Juneau was badly damaged by a Japanese torpedo. The next morning, it was struck by another torpedo, which detonated the Juneau’s magazines and blew the ship apart. It sank in just 42 seconds.

The ship’s destruction resulted in 687 casualties; only 10 people survived. Three of the Sullivan brothers — Francis, Joseph, and Madison — were killed instantly. Albert drowned the next day. George, who was badly wounded, managed to make it to a life raft. He lived for a few days but ultimately perished at sea, possibly from the sharks that circled the survivors.

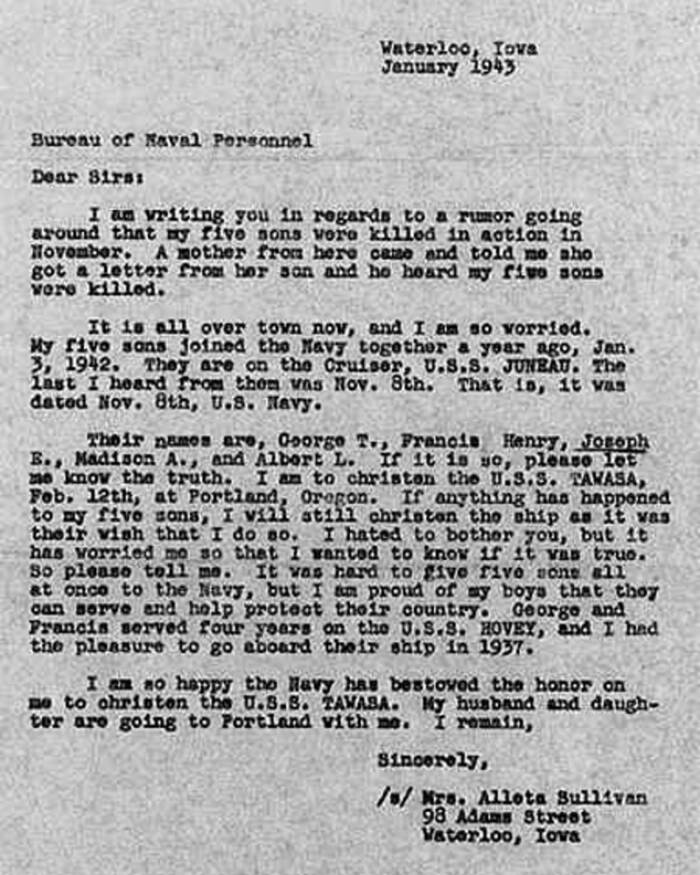

But news of the Sullivan brothers’ deaths traveled slowly. In January 1943, their mother Alleta wrote a letter to the Bureau of Naval Personnel to try to get information about what had happened:

“I am writing you in regards to a rumor going around that my five sons were killed in action in November,” Alleta wrote. “A mother from here came and told me she got a letter from her son and he heard my five sons were killed… If it is so, please let me know the truth… I hated to bother you, but it has worried me so that I wanted to know if it was true. So please tell me. It was hard to give five sons all at once to the Navy, but I am proud of my boys that they can serve and help protect their country.”

According to the Des Moines Register, the Sullivan family was officially notified that the Sullivan brothers were missing in action on Jan. 12, 1943. The next day, Jan. 13, President Franklin Roosevelt penned a personal letter to the Sullivans’ bereaved parents.

National ArchivesAlleta Sullivan’s January 1943 letter seeking information about her five sons, who were all missing in action.

“The knowledge that your five gallant sons are missing in action against the enemy inspires me to write you this personal message,” Roosevelt wrote to Thomas and Alleta. “I am sure that we all take heart in the knowledge that they fought side by side. As one of your sons wrote, ‘We will make a team together that can’t be beat.’ It is this spirit which in the end must triumph.”

Indeed, the Sullivan brothers would not soon be forgotten.

How The Deaths Of The Sullivan Brothers Impacted The War Effort

The nation met the story of the Sullivan brothers with an outpouring of sympathy. Their deaths became a “rallying point” for the war effort.

The Navy memorialized the Sullivan brothers by naming two ships “The Sullivans” in their honor. Their story was even dramatized in a 1944 movie, The Fighting Sullivans, which presented the siblings as heroic, all-American martyrs of the war effort.

U.S. National Archives and Records AdministrationA wartime poster featuring the Sullivan Brothers. Their deaths galvanized the war effort.

Thomas, Alleta, and Genevieve Sullivan also did their part. Genevieve joined the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). She and her parents traveled across the country to manufacturing plants and shipyards to encourage workers to produce weapons so that the war could finally come to an end. By January 1944, they’d spoken to over a million workers in 65 cities and reached many more over the radio.

The deaths of the Sullivan brothers also highlighted the potential tragedy of multiple siblings serving at once. However, the Sullivan family was hardly the only one to lose more than one son during World War II. In 1944, Sgt. Fritz Niland of the 101st Airborne Division was sent home after his three brothers were killed in the war — a story which later inspired the film Saving Private Ryan.

That said, the deaths of the Sullivan brothers had no immediate effect on U.S. law. Naval policy already discouraged siblings from serving together on the same ship. In fact, the Sullivan brothers had specifically appealed this policy in order to “stick together” on the USS Juneau. Later laws, however, gave draft exemptions to families who’d already lost one or more children to military service.

Ultimately, the Sullivan brothers will be remembered both for their loyalty to the nation during World War II and their loyalty to each other. Both Navy ships named after them adopted the Sullivan brothers’ motto: “We Stick Together.”

After reading about the Sullivan brothers, discover the true story of Easy Company from the TV show “Band of Brothers.” Or, discover the story of Doris Miller, the Black cook who became a hero during Pearl Harbor.