Thomas Midgley Jr. was a proponent of technology's capacity for good, but he helped put lead in the air and annihilate Earth's ozone layer.

We all have a legacy. Every one of us will eventually pass on, generally hoping to have left the world a slightly better place than it was when we found it. Scientists often epitomize this hope, many of them toiling for decades in obscurity as they work to find answers to humankind’s many problems.

In that sense, Thomas Midgley Jr. was a great man and a fine scientist. Working for General Motors during the early days of the automobile, Midgley earned over 100 patents and was showered with honors by the scientific community.

Unfortunately, Midgley was the most dangerous kind of man: a reverse genius.

With a strong work ethic and an unyielding sense of optimism about the future of technology, Midgley displayed an absolutely uncanny instinct for doing what we now recognize as the wrong thing, and then for building those things into multimillion-dollar industries that would take generations to dismantle.

Entirely on accident, Midgley helped poison three generations of children, greatly increased the risk of skin cancer in Australia, and contributed mightily to the global warming that many of us are still pretending isn’t our fault.

Next up: The deliberate, profit-minded choice that devastated the environment…

How Gasoline Became Gasoline

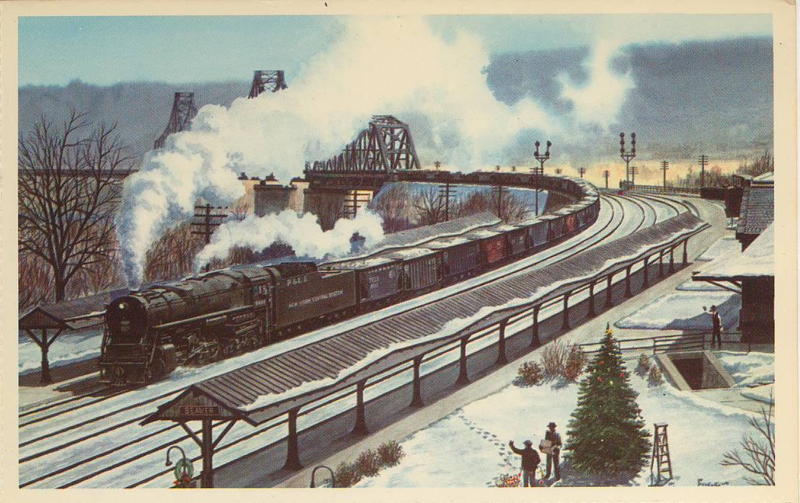

Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania.

Nothing about Thomas Midgley’s early life suggested a future filled with crimes against humanity. He grew up in a stable, happy home in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, and learned how to tinker with machinery in the workshop of his father, an old-fashioned American inventor and handyman.

By dint of hard work, careful savings–and possibly apple pie and baseball–Midgley eventually earned entrance into Cornell University, graduating with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1911.

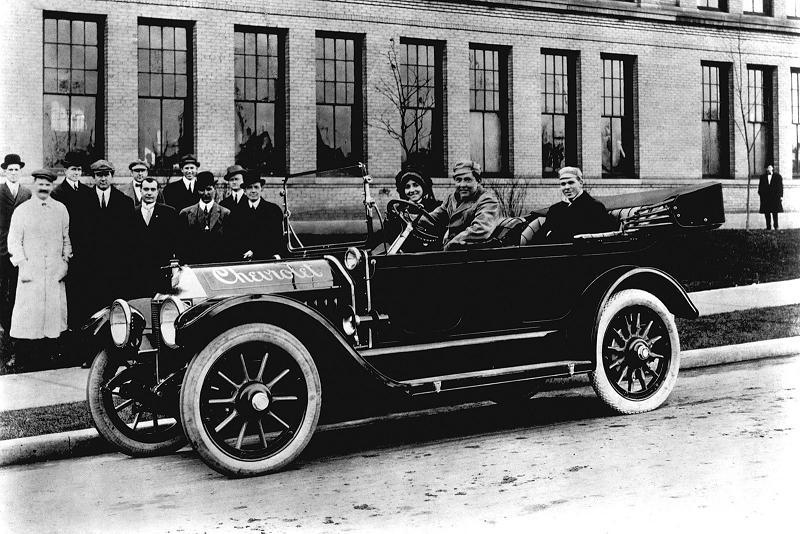

The first GM Chevrolet model ever produced. Image Source: D Business

He then went to work for a young car company called General Motors. When Midgley joined the team, he found them at a loss over the problem of engine rattling. As it happens, a solution already existed–add ethanol to the gasoline, which many are trying to get the government to subsidize now–but ethanol is produced by nature and can’t be patented. That means GM couldn’t make money off of ethanol additives, which means the engine-knocking problem was officially not fixed until something artificial and expensive could be developed.

Knowing that the knocking was a result of how the gasoline burned in the cylinders, Midgley tried adding iodine to stain the fuel red and change gasoline’s heat-absorption properties.

When that didn’t work, he started working his way down through the elements, experimenting with each, until he found lead. Leaded gasoline–containing GM’s proprietary ethyl lead compound, thank you very much–eliminated engine rattling and even improved mileage somewhat. Before long, virtually all gasoline used in the world contained lead.

“Yeah, Pop. Don’t be so goddamn lame!”

Next up: The terrible things lead does to the human body…

How To Poison Children

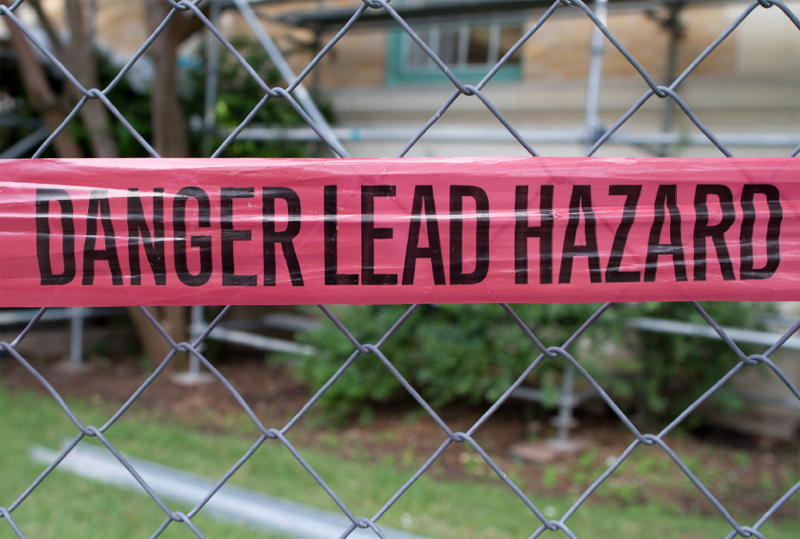

Image Source: www.cec-environmental.com

Exposure to lead is especially harmful to children because a.) they’re more likely than adults to ingest it, b.) it’s more likely to pass into a child’s bloodstream than an adult’s, and c.) it has profound effects on neurological development that last a lifetime. And thanks to Midgley’s work, hundreds of millions of cars spent the next 50 years belching out a torrent of lead-heavy exhaust all over the world.

The tragedy about leaded gasoline is that everybody knew it was toxic, but the important players–including Midgley himself–were all making money, so nothing was done to curb lead’s destruction for half a century.

Said Midgley in 1923, just before he went to Florida to convalesce: “After about a year’s work in organic lead, I find that my lungs have been affected and that it is necessary to drop all work and get a large supply of fresh air.”

Developed countries gradually phased out leaded gasoline through the 1970s and 1980s, with final bans taking effect in the 1990s.

Next up: What World War I weaponry and refrigerators have in common…

How Your Refrigerator Works

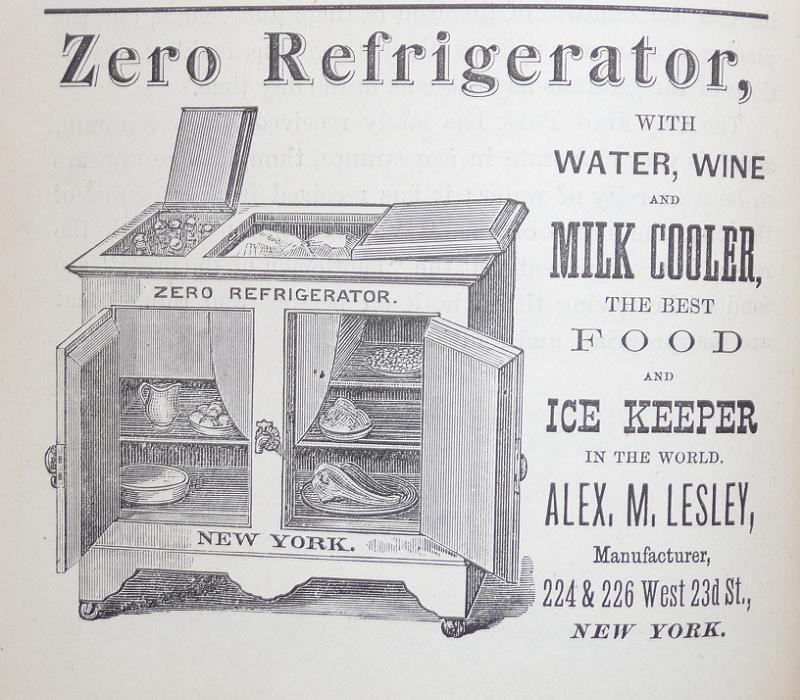

There’s a reason your grandmother called the refrigerator an “icebox”: in the 1920s, most people kept food cool by putting it inside a box under a block of ice that had to be delivered daily by a truck. Early refrigerators like Frigidaire, a GM-owned brand, used coolants and pumps to produce low temperatures without the ice.

These coolants must be volatile, inert, and cheap. Early cooling units used water, which isn’t inert and is in fact a powerful solvent; or ammonia, which is plenty volatile, but smells bad and can poison people at high exposures. By the early 1920s, GM was looking for a new chemical that would meet all three of the desired criteria.

Ideally without ending life on Earth

Enter Thomas Midgley Jr. He knew that a class of compounds called alkyl halides met both of the first two criteria, so the search began for a chemical in this class that would be cheap and non-toxic.

Eventually, Midgley’s team settled on dichlorodifluoromethane, which is simply a mix of truly awful chemicals. Chlorine, for example, is so toxic on its own that it was used as a weapon during World War I. Methane is highly flammable. As for fluorine, well…just have a look at what it does when it’s free to bond with iron:

The trick to making dichlorodifluoromethane, or “Freon,” as it conveniently became known, is to use all of the constituent elements’ most hazardous features against each other to achieve some kind of balance. It worked; the compound was safe for home use, but not at all safe for the environment.

Next up: How exactly we put the hole in the ozone layer…

The Most Dangerous Compounds On Earth

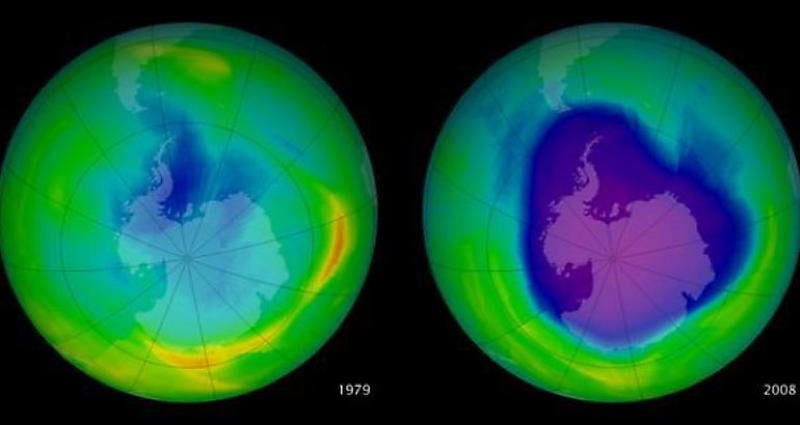

The depletion of the ozone layer (green) between 1979 and 2008.

The funny thing about unintended consequences is that they usually have an ironic sense of humor.

The very properties that made Freon and other members of its group of compounds, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), useful for refrigerants and propellants (think of old-fashioned hairspray) were the properties that made them so damn dangerous that their production is now heavily restricted and criminalized around the world.

When CFCs are released into the environment, no natural chemical process breaks them down. As a result, CFCs from the hairspray Robert Smith used in 1985 are still out there, somewhere, drifting around in the atmosphere. Eventually, CFCs released at ground level waft up into the upper atmosphere, where they are bombarded with cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays are highly energetic–if they had the mass of a grain of sand, each would strike the Earth with the force of a half-kiloton bomb–and about 100 of them strike every square meter of the Earth each second.

Image Source: YouTube

When a molecule of Freon gets hit, it splits open and its guts spill out. And all of the elements in Freon destroy the ozone layer. Ozone is a stable form of molecular oxygen that catches ultraviolet light from the Sun. We depend on it to live.

If ozone can’t catch enough high levels of UV light, our problems go way beyond skin cancer: the UV light will induce a reaction in Earth’s soil that produces hydrogen peroxide, which effectively kills soil bacteria. Without these bacteria, plants can’t plants can’t survive and the soil will turn red with rust.

In the century or so before it’s scrubbed from the air, a single chlorine atom from a CFC can break over 100,000 ozone molecules. This is being written in 2015. As of now, the chlorine from every CFC molecule ever produced is still out there, and the last of them won’t be gone until the end of the 21st century.

Next up: Thomas Midgley Jr.’s eerily fitting end…

One Invention Too Far

Image Source: www.mirror.co.uk

Few of the consequences of Thomas Midgley Jr.’s work were known during his lifetime, and Midgley had the satisfaction of dying a prosperous, successful scientist. Midgley racked up one patent after another, and the scientific community could hardly restrain itself from sneaking love notes into his locker.

He was elected to the National Academy of Scientists, which only around ten percent of American scientists ever accomplish, and he won the prestigious Priestly Medal from the American Chemical Society, of which he would later serve as president and chairman.

Midgley’s death was every bit in keeping with his cursed life. In 1940, he contracted polio, which left him severely handicapped. Approaching his disability as he approached the issues of auto fuel and refrigerants, he set about designing something that would turn out to be lethal.

Midgley devised an elaborate system of levers and pulleys to help him get out of bed unaided and had it installed in his bedroom. In 1944, the 55-year-old Thomas Midgley Jr. was found wrapped in the device’s cables, having been strangled by his own invention.

For more on climate change, check out the beer-powered future of cars, Pope Francis’ most illuminating thoughts on the issue, and haunting renderings of our planet in a new ice age.