From vanishing islands to the Snake Island filled with Golden Lancehead Vipers, these tiny islands aren't exactly welcoming vacation spots.

Tiny Islands That You’ll Never Visit: Snake Island, Brazil

Off the coast of Brazil sits Ilha de Queimada Grande, or as it’s known in colloquial English, Snake Island. Comprising roughly 110 acres of trees, the island is uninhabited and travel to it is expressly forbidden by the Brazilian navy. Why? Because Queimada Grande is home to hundreds of thousands of golden lanceheads, the snake pictured above.

Unique to Queimada Grande, the golden lancehead typically grows to be about two feet long but at times can grow to nearly double that length. And its venom is poisonous. Very, very poisonous.

Generally, lanceheads are responsible for 90% of snake bite-related fatalities in Brazil. The mortality rate from a lancehead bite is 7% if the wound goes untreated — and as high as 3% even if treatment is given. The venom causes a grab bag of symptoms which includes kidney failure, necrosis of muscular tissue, brain hemorrhaging, and intestinal bleeding. Scary stuff, to be sure.

For Snake Island, the picture is even scarier. The data above does not include bites from the golden lancehead, as there are no official records of a golden lancehead-caused fatality due to the de facto quarantine on the Brazilian island. A chemical analysis of golden lancehead venom suggests that the snake is much more dangerous than its continental cousins: golden lancehead viper venom is faster acting and more powerful — perhaps five times more powerful.

Two foot-long snakes with such powerful venom, combined, means that getting close to one carries with it a high risk of death. And getting close to one is all but certain on Snake Island. Even the most conservative estimate suggests that the golden lancehead population density on Queimada Grande is one per square meter; others suggest a population as high as five per square meter.

Regardless, as one site points out, even at the lower estimate, “you’re never more than three feet away from death.” Thus this place is among the scariest of all Earth’s tiny islands.

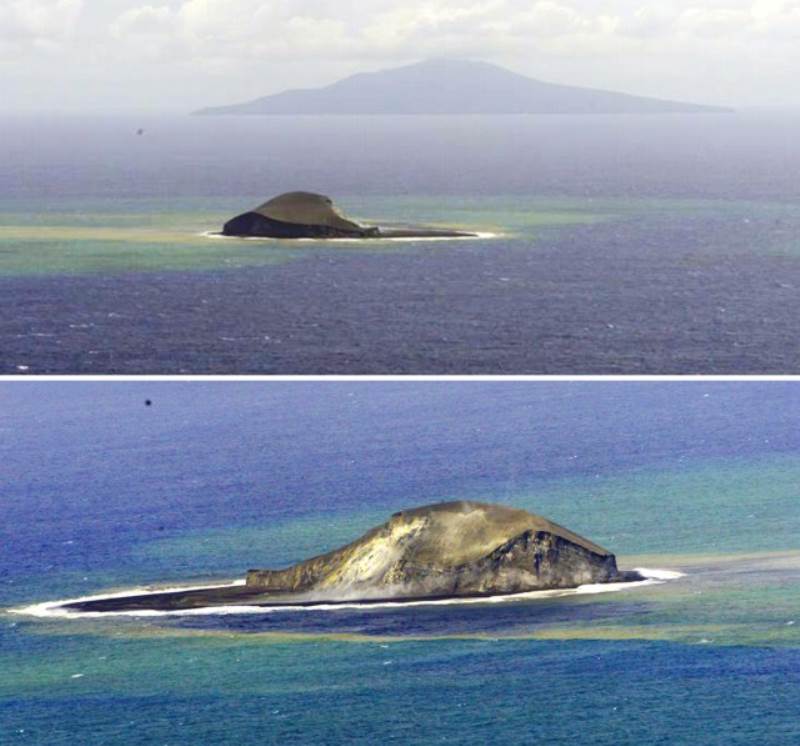

Home Reef, South Pacific

Imagine cruising around the South Pacific and encountering a beach in the middle of nowhere (really!), surrounded entirely by ocean. Upon further exploration, the beach isn’t sand — it’s made of pumice, volcanic stones floating on the water. And where there are volcanic stones, there’s a volcano. In this case, the volcano is under the water’s surface, about to erupt and, in doing so, create an island.

If you’re Fredrik Fransson of Australia, there’s no need to imagine. In August 2006, it actually happened. And while Fransson probably thought he was watching an island form anew, he wasn’t quite right. The island, one of Earth’s most unique tiny islands, was forming again. This landmass, known as the Home Reef, is an “ephemeral island” — one which forms, erodes, and re-forms (and erodes again) over the course of years.

Situated closer to Tonga than anything else recognizable — and it’s still a few hundred miles from Tonga — the island was first formed by an 1852 submarine volcanic eruption. The island eroded away over the years only to re-form again in 1984 after another eruption. Home Reef again disappeared soon after — and, in 2006, re-emerged.

It’s obviously not inhabitable — beyond being temporary, it’s made of lightweight rafts of pumice. But it’s not entirely unappealing: NASA suggests that Home Reef (and other pumice raft islands) may be used by marine life as migratory stop-overs.

Or, at least, once-in-a-lifetime sightseeing opportunities for lucky folk like Fransson.

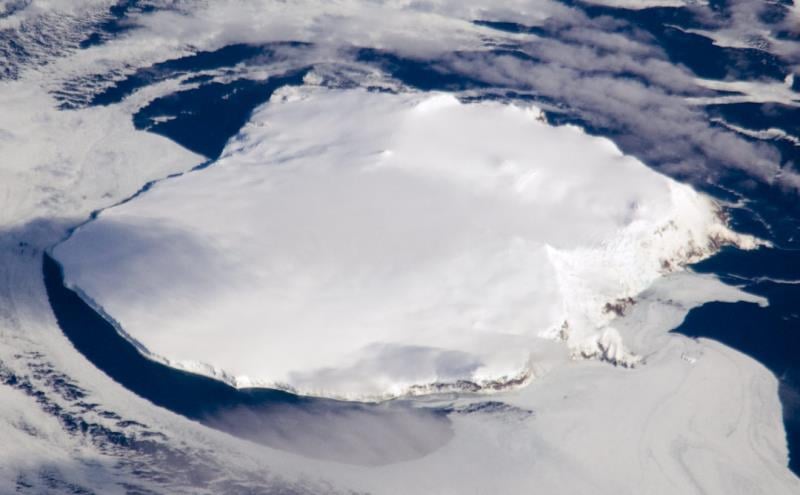

Bouvet Island, South Atlantic

If there is a middle of nowhere, it is Bouvet Island, a 19-square mile piece of uninhabited and glacier-covered land in the South Atlantic. It is the world’s most remote island (and probably the creepiest of Earth’s tiny islands), nearly 1,000 miles from another swath of land (a sector of Antarctica called Queen Maud Land). The island is 1,400 miles from the nearest inhabited landmass (Tristan da Cunha, another remote island) and 1,600 miles from South Africa — roughly the distance from Paris to Moscow.

Originally discovered in 1739 by Norwegian explorer Jean Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier, the island is a wasteland of rocks and ice that lacks all vegetation aside from the occasional lichen or moss. Since 1929, it’s been a territory of Norway, and in 1977, an automated weather monitoring station was built on the island. But the island’s biggest oddity came to light in 1964, when a boat was discovered on the island without explanation.

With Norway’s permission, the South African government was investigating the construction of a manned station on the island and set out to see if there was enough flat land space on Bouvet Island to meet their needs. It didn’t.

But in April of 1964, South African officials returned to finish their study of the newer parts of the island — and found a mystery. A boat, marooned on the island, with a pair of oars a few hundred yards away, lay in a lagoon within the new land mass. The boat lacked any identifying markings and, although there was some evidence that people were on the boat, no human remains were found.

The open questions are numerous. Why was a boat anywhere near the area — quite literally, in the middle of nowhere? Who was on the boat? How did they get there — over a thousand miles from civilization — with nothing more than a pair of oars? And what happened to the crew? The answers are few and far between, as noted by London historian Mike Dash, who took an in-depth look at the question, but came away with nothing even approaching a concrete answer.

Given the remoteness of Bouvet Island and its inhospitable landscape, the identity of the boat and its potential crew has gone mostly unexplored for a half-century. And much like the story of the island itself, the boat’s identity will likely remain a mystery.

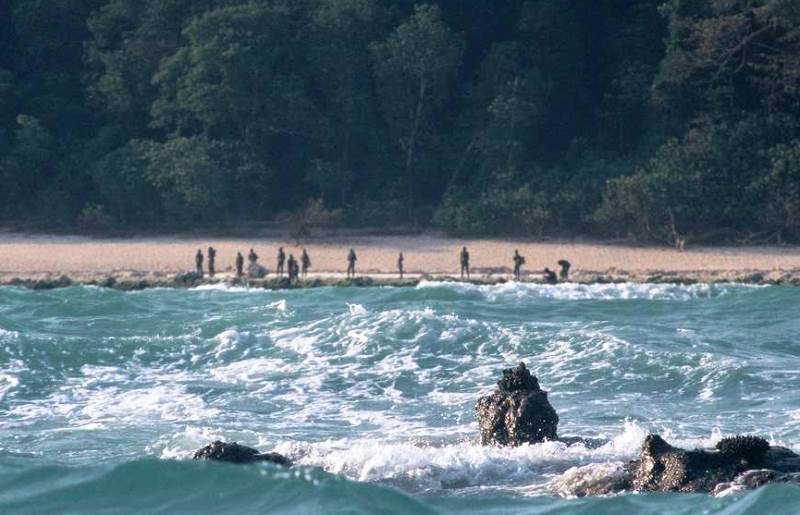

North Sentinel Island, India

Comprising the eastern shore of India and the shores of Bangladesh and Myanmar, the Bay of Bengal is no stranger to legend. Located within the bay is the Indian-controlled North Sentinel Island, which is little more than a dot of land yet one of Earth’s most interesting tiny islands.

Between 50 and 400 people are estimated to live on North Sentinel Island. These people, known as the Sentinelese, are perhaps the most isolated people in the world and are believed to be pre-Neolithic — literally, technologically in the Stone Age. By and large, the Sentinelese have gone without contact from outsiders for centuries if not millennia — in part because the Sentinelese do not take kindly to visitors.

In 1967, Indian authorities began their first meaningful attempt to engage the Sentinelese by leaving coconuts as gifts on the island’s shores. While some progress was made over the course of a few decades, the quality and quantity of contact was minimal at best.

Seven years later, anthropologist Trilokinath Pandit and a film crew attempted to woo the Sentinelese into friendly contact with gifts, such as fruit, a pig, some toys, and pots and pans.

The result was not positive: a film director was shot in the thigh with an arrow. In the 1990s, India cut off its permission for these anthropological endeavors, citing risks seen in contacting other indigenous tribes as well as the fear of introducing diseases from mainland India to the Sentinelese people, whose physiologies almost certainly would be ill-prepared to combat.

More recent events strongly buttress that the Sentinelese support this decision to cut off hopes of contact. In 2006, a pair of fishermen were plying their trade, illegally, off North Sentinel Island’s shore. Sentinelese archers killed the fishermen. When a helicopter came to recover the bodies, the helicopter too was met with a hail of arrows, and retreated before fulfilling its mission.

What do we know about the Sentinelese?

Understandably, very little. They live in huts and are hunter-gatherers, employing the use of javelins, bows and arrows and harpoons. They speak a language unique to them (also called, by outsiders, “Sentinelese”) which we have no way of translating. The Sentinelese appear to use pig skulls as ornaments of some sort and have used red dye in both clothing and what is best guessed to be decoration.

And that, unfortunately, is all we may ever learn. As India has given up almost all hope of spurring further contact with the Sentinelese, these people are considered autonomous and, in a very real sense, the most isolated people on the planet. It seems like a matter of time before they and their culture die off, becoming a footnote in history.

On the other hand, the Sentinelese are resilient — some estimate that they have lived on North Sentinel Island for 60,000 years, and in any event, the Sentinelese somehow survived the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 (which probably hit the island).

If you enjoyed this article about tiny islands, check out our articles on bizarre ocean creatures and the world’s most bizarre landscapes! Then, check out six of the most remote places on planet Earth.