As tulip prices shot up by 1,000 percent in the 1630s, Dutch investors scrambled to buy up bulbs still in the ground. But months later, the bubble burst.

In the 17th century, history’s first speculative bubble popped. Over a period of months, Dutch traders had invested more and more money into tulip bulbs, believing the exotic flowers would make them a fortune.

“He who considers the profits that some make every year from their tulips will believe that there is no better Alchemy than this agriculture,” a 17th-century poet wrote during this so-called “tulip mania.”

But tulip mania proved to be even riskier than actual alchemy. After tulip prices skyrocketed in the 1630s, the bubble burst.

Tulip mania served as a warning to all of Europe’s merchants: that fortunes could be destroyed as quickly as they were made.

Conditions Were Ripe For A Tulip Market

Jean-Léon Gérôme/Walters Art MuseumAn 1882 painting titled “Tulip Folly” by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The mania all began in the 1500s when western tourists to the Ottoman emperor’s court in Constantinople happened upon his tulips. They became enamored. Soon, western traders shipped the bulbs back to France where they spread to the Netherlands.

The Netherlands in the 17th century boasted one of the strongest economies in Europe. With a focus on commerce, Amsterdam became a trade capital for the continent. In 1602, the Amsterdam stock exchange opened, bringing even more opportunities to invest in exotic markets.

Plus, according to Anne Goldgar, author of Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Golden Age, collecting things both expensive and from exotic lands was in vogue.

Tulips were especially fashionable because “there’s a fashion for science and natural history, especially among people who are humanistically educated and relatively well off.”

So the kinds of people who collected tulip bulbs likely had the money to collect other luxury items like paintings, too.

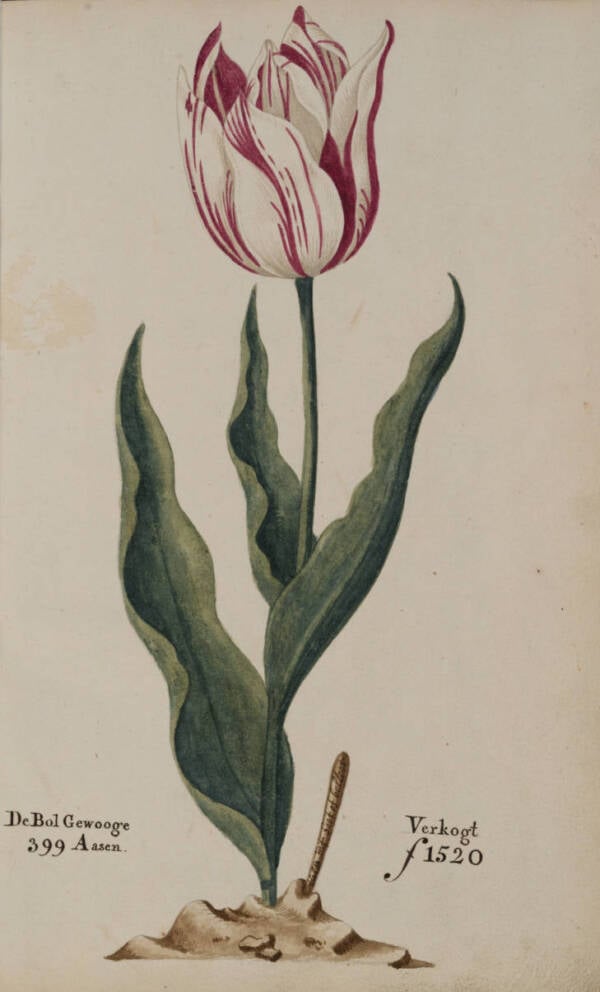

P.Cos/Wageningen University & ResearchA 1637 catalogue lists tulip prices at 1,520 guilders per one flower.

Tulips also grew to be especially popular because they held an element of surprise: There was no guarantee that a brown bulb might explode into rich colors or striped and speckled petals.

“You didn’t really know what was going to happen with your tulips,” Goldgar told the BBC. “People loved the fact that they constantly were changing.”

As a result, wealthy merchants and craftsmen developed an insatiable desire for tulips by the 1630s.

The Price Of Tulips Blooms

By 1636, demand for tulips took off. But it was still winter and the bulbs were trapped beneath the frozen ground. In the taverns of Amsterdam, traders exchanged promises to buy the tulip bulbs come spring, creating a highly expensive futures market.

But tulip mania really exploded in early 1637. Prices saw a thousandfold increase on Dec. 31, 1636, when Dutch traders sold one popular bulb for 125 guilders (old Dutch currency) a pound.

Just over a month later, on Feb. 3, 1637, that same tulip went for 1,500 guilders.

Jan Brueghel the Younger/Frans Hals MuseumA circa 1640 satire of tulip mania by Jan Brueghel the Younger.

“Neighbors seemed to talk to neighbors; colleagues with colleagues; shopkeepers, booksellers, bakers, and doctors with their clients gives one the sense of a community gripped,” Goldgar wrote. “And enthralled by a sudden vision of its profitability.”

The price for tulips skyrocketed based on the belief that the flowers would fetch higher prices come spring. One pamphlet listed prices as high as 5,200 guilders for a specialty bulb – the price of a home — at a time when skilled craftsmen made around 300 guilders a year.

It would take that craftsman more than 17 years to afford one bulb.

Yet long before spring, the tulip bubble burst.

The Tulip Trade Crashes Before Any Bulbs Change Hands

Hendrik Gerritsz Pot/Frans Hals MuseumIn an allegorical painting, the goddess of flowers cavorts with drinking traders.

Ironically, tulip mania collapsed before spring even began. Before anyone could even get their hands on their priceless bulbs, the market for them crashed. But why?

Some scholars speculate that the crash began when traders realized how vastly overinflated the market had become.

Other scholars indicate a more specific moment.

During a tulip auction in Haarlem on Feb. 3, 1637, the auctioneers failed to sell a single bulb. Buyers became convinced that tulips were overpriced and prices suddenly tumbled.

It became fashionable for religious sermons to target buyers who inflated the mania and warn people not to fall for similar “rags to riches” promises.

Mythologizing Tulip Mania

P.Cos/Wageningen University & ResearchA 1637 catalogue lists a tulip bulb for 1,500 guilders.

The fictional financier Gordon Gekko called tulip mania “the greatest bubble story of all time” in the movie Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. But many real historians would dispute this.

In fact, the myth of tulip mania is often exaggerated. Even though it’s called “tulip mania,” the whole country didn’t feel its aftereffects.

Goldgar maintained that only a few, super-wealthy Dutchmen were actually involved in the trade and even they weren’t hurt too badly by the burst bubble.

“I looked to try and find anybody that was made bankrupt because this is the myth of course that people were drowning themselves in canals because they were made bankrupt,” she reported to the BBC. “Actually I couldn’t find anybody that was bankrupt because of tulip mania.”

Since many buyers never paid out the promised price, few actually went bankrupt.

If anyone was actually hurt by the craze, it was the tulip growers. In April 1637, the government stepped in to cancel all tulip contracts. As a result, growers didn’t receive the money buyers had promised them come springtime. Growers then struggled to find new buyers at the last minute.

So how did the myth of tulip mania start? Many trace it back to the 19th century when Scottish writer Charles Mackay wrote an explosive history of the tulip craze.

Jan Brueghel the Younger/Wikimedia CommonsPainter Jan Brueghel the Younger warns against the tulip speculation.

According to Mackay, when the bubble burst the nation’s economy was destroyed and ruined Dutch investors threw themselves into the canals. Mackay’s vivid descriptions shaped how many see tulip mania today, though Goldgar has largely disproven them.

Even if it’s not as morbid as some may have thought, the history of the tulip boom holds a valuable lesson about the economy.

What Tulip Mania Revealed About Economics

Even if no one ended up in a canal over the tulip bubble, the experience did serve as a warning to future investors about the nature of the marketplace.

After all, the failure of the tulip market was followed by other bubble bursts: the South Seas bubble in the 1720s, the railroad bubble of the 1840s, and the bull market of the 1920s.

Claude Monet/Musée d’OrsayMonet’s 1886 painting of tulip fields in Holland.

In retrospect, each speculative bubble seems nonsensical. Why would Dutch traders pour their fortunes into something as ephemeral as a striped flower?

The pattern nonetheless repeats itself through history and reveals the role of trust in the market and the cost of losing faith in a valuable product.

For more about plants that shaped history, learn how a British botanist destroyed China’s economy by stealing tea leaves. Then, check out the aftermath of the Roaring ’20s with these photos of the Great Depression.