From institutional racism and corporate machinations to government incompetence, these four elements of our electoral process explain why it's not the people who actually choose the president.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

With the start of 2016, election year is now upon us.

While you certainly know that, come November, we’ll elect our next president, what you may not know–or may have blocked out of your mind–is that January 6, 2016 marks the 15th anniversary of a rather important moment in the history of U.S. elections.

On January 6, 2001, after one of the closest presidential races the U.S. had ever seen—and a long recount mired in controversy, only to be ended by an order from the Supreme Court—Congress declared George W. Bush the official winner of the 2000 presidential election. As a result of contested Florida ballots, this declaration occurred more than five weeks after the election had taken place.

Outside of Congress, among the average Americans who had gone out to the polls five weeks before, what made this result so astounding was that Bush’s opponent, Al Gore, had actually won the popular vote–yet he was not elected. However, when the Supreme Court ended the Florida recount, that state’s 25 votes in the electoral college (more on that later) went to Bush, giving him the victory in the electoral college, and thus the presidency.

As crazy as that all sounds, it was actually the third time that a presidential candidate had won the popular vote and lost the election.

The U.S. electoral system is full of unbelievable, shall we say, “quirks” that disrupt the integrity and the basic logic of the democratic process. From the Electoral College to absurd voter restrictions, these laws and processes actually help decide who will run our country. Starting with the electoral college that gave Bush his victory 15 years ago, here are four of the most unbelievable U.S. election laws…

The Electoral College

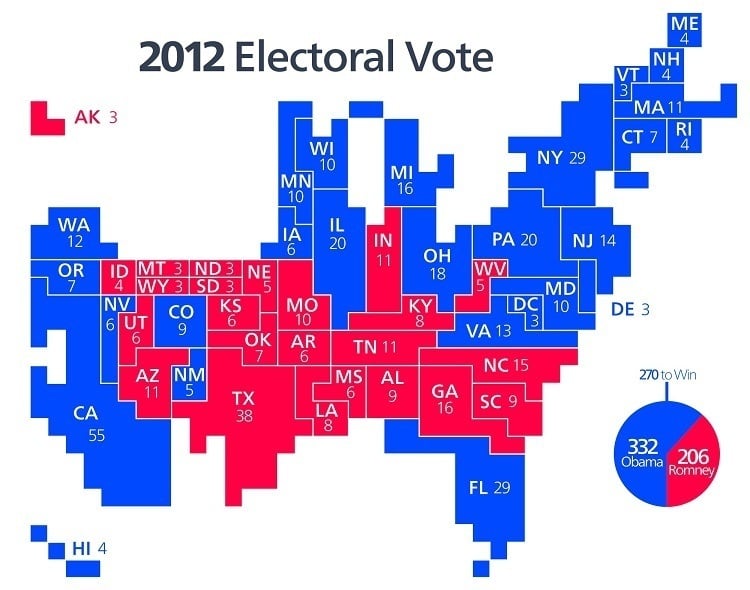

The results of the 2012 presidential election in the Electoral College, showing how many electoral votes are granted to each state. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The first thing you have to understand is that we don’t actually decide who becomes president–the Electoral College does. When you vote for a candidate, you’re not actually directly voting for that candidate.

Instead, you’re voting for the designated Electoral College elector, who has pledged to vote in favor of that same party you’ve voted for. So, if your state’s popular vote goes Republican, then the Republican electors from that state (usually chosen by the party’s presidential nominee, not the Democrat electors) are the ones who get to cast their votes for President in the Electoral College. Then, on the Monday following the second Wednesday in December, the Electoral College meets and decides who becomes president.

The number of electors from each state is equivalent to the number of congress members representing the state. Therefore, states with larger populations have more electors. And that might be the only thing about the Electoral College that makes much sense.

The thing that is perhaps most unbelievable and appalling about the whole process is that while electors pledge to vote for the candidate they represent, they don’t always have to. In fact, throughout U.S. history, there have been 157 “faithless electors,” ones who have, say, voted Democrat when they’d previously pledged to vote Republican, or vice versa. And less than half of U.S. states have laws preventing this. So, essentially, when you vote for a presidential candidate, you’re not so much voting for that candidate as you are placing power in the hands of an elector you don’t know and who can do what they please with that power.

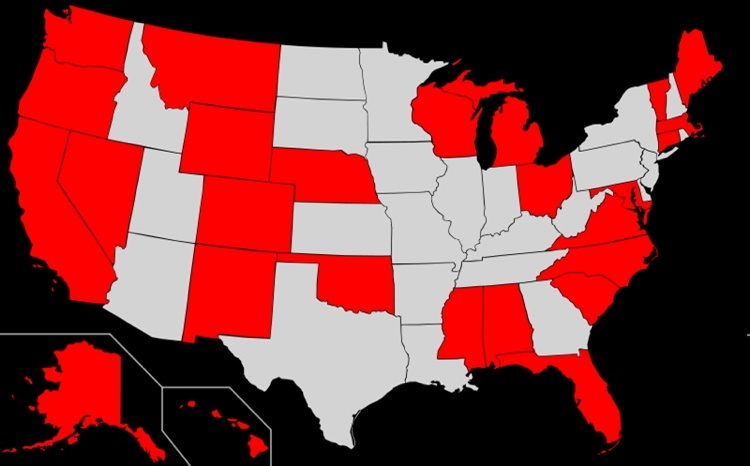

States in red are currently the only ones that have laws preventing the activities of faithless electors. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Now, most of the time, the electors vote as pledged and the Electoral College accurately reflects the mandate of the people–but not always. In 1836, 23 faithless electors from Virginia conspired to stop Richard Mentor Johnson from becoming vice president. The following year, the Senate reversed this, Johnson became vice president, and that was the closest faithless electors have ever come to changing the ultimate result of an election.

But that doesn’t mean it can’t happen, and doesn’t still happen today. In what is perhaps the most astounding–and frightening–case, a Minnesota elector in 2004 who had pledged to vote for the John Kerry/John Edwards ticket cast his or her presidential vote for “John Ewards.” Of course, that one botched vote didn’t ultimately matter, but it’s chilling to think that our presidential elections can, even a little bit, be swayed by things like that.

All that said, when the Electoral College was first established, in 1787, it was appropriate for its time. Because information wasn’t nearly as accessible and couldn’t easily be disseminated over large distances, the masses would not know enough about candidates from outside their own state in order to make an informed decision in a nationwide election.

There was a chance that a single president would not emerge by majority vote because each population would just elect the name they knew from their home state. Today, however, it’s beyond obvious that this–and the Electoral College itself–no longer applies.

Gerrymandering

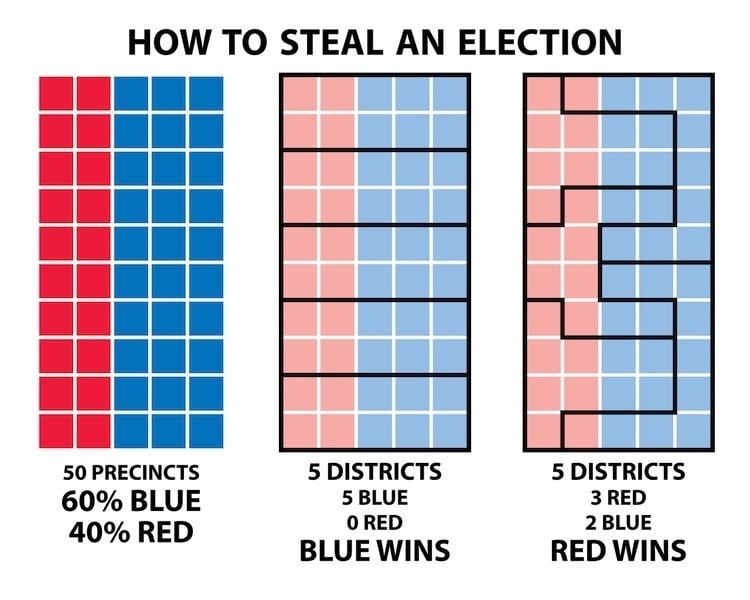

A simple diagram reveals how the way in which districts are divided can change the result of an election, regardless of the popular vote. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

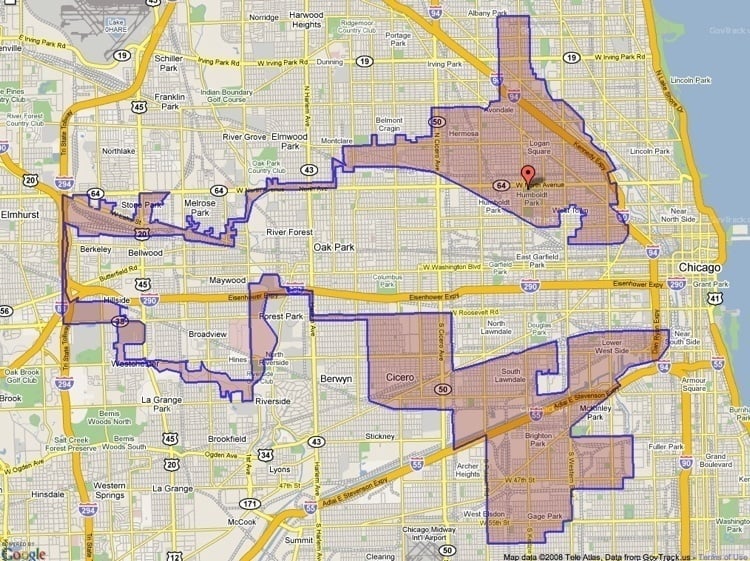

Gerrymandering is and has long been one of the largest, most destructive problems with the entire U.S. electoral system. In short, gerrymandering is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to ensure, or at least promote, a particular outcome. For example, depending on how a state is divided into districts, the exact same voting results can produce different electoral results.

When dividing a state into districts, you’d think that simple geographic, municipal, or population-based ranges would do the trick. However, political parties have a great incentive to manipulate the district lines to suit their needs. You could pack a group of people (usually, it’s an ethnic group, making racism the underlying force at work) presumed to vote a certain way into one district so as to contain them and minimize their influence on other districts.

Alternatively, you could disperse a group of people presumed to vote a certain way into many districts so as to dilute their influence on any one district and prevent them from having much influence at all. While many laws and court rulings have sought to, and sometimes succeeded in, limiting or even reversing the effects of gerrymandering, it is still very much an issue today.

A map showing the highly irregular borders of Illinois’ 4th congressional district, gerrymandered in order to pack two majority Hispanic areas into one district.

Super PACs

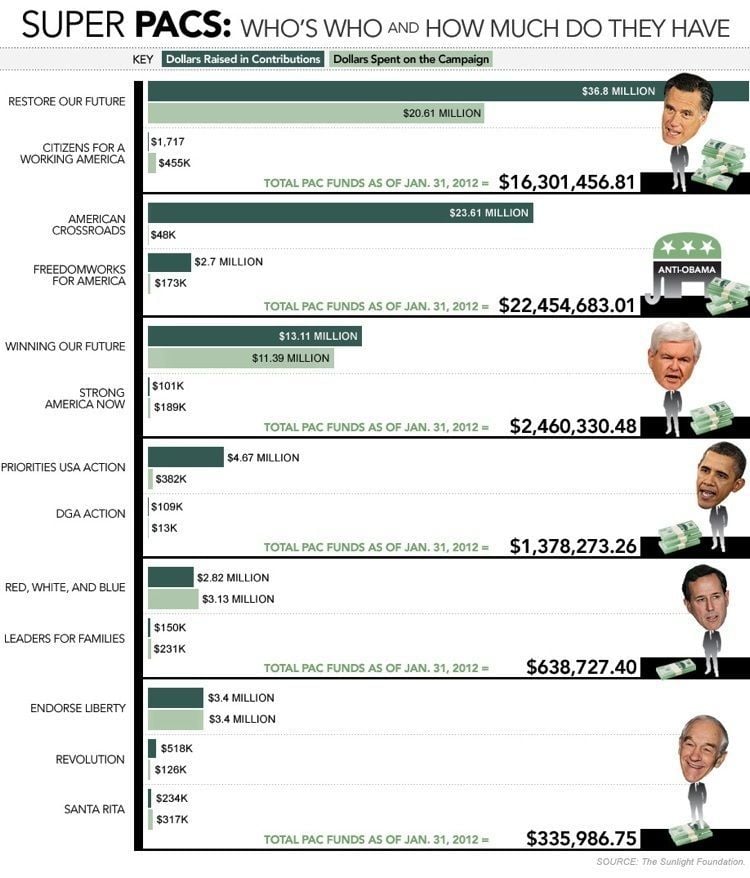

The amount of Super PAC money received by each candidate in the 2012 presidential election. Image Source: Slate

A Super PAC, or Political Action Committee, is a fairly recent yet highly influential development in U.S. presidential elections. These groups had a huge impact on the 2012 election and will once again do so this year. Super PACs are independent political committees that support a specific candidate.

Often through anonymous donations, a Super PAC may raise unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals that can be used to promote a certain candidate. Donor names must eventually be given to the Federal Election Commission, however, this can be done merely on a monthly or semi-annual basis, allowing things to slip through the cracks, if only temporarily.

Before Super PACs, campaigns were often publicly funded and had strict spending limits that were highly regulated. Candidates were required to keep detailed records of all transactions, including donations.

However, Super PACs skirt around all these limits. By law, they cannot directly contribute to the candidate, because candidates are required to limit spending to the public fund provided. But, since the money is technically independent from the candidate, it can be used in any way to support the candidate. For instance, Super PAC funds are often used to create negative ads about the opposition.

The result of the Super PAC phenomenon is that the presidential race becomes a battle between candidates to prove who has richer friends, and thus more money to spend. This not only encourages insane spending and widespread, often spurious, attacks on opponents, but it also creates a strong bond between corporations and political parties with similar agendas.

Now, political races have always been about money, campaign financing has always been corrupt, and corporations and individuals with certain agendas have always been in bed with politicians, but the rise of Super PACs has allowed this kind of activity to skirt the law and worm its way ever further into the mainstream.

Voting Restrictions

Image Source: Brennan Center for Justice

The 2016 presidential election will see 15 states with new voting restrictions in place. These states have lawfully introduced bills that restrict voters and tend to affect specific demographics (once again, more often than not, institutional racism is at work here) that may vote against the political status quo of the given state. Such restrictions include stricter voter ID laws, reduced early voting period, curbed registration drives, and more severe limitations on people with past criminal convictions.

The states implementing these laws claim it will remove fraud and protect the integrity of the elections. Many others claim that–like so many of the other absurd laws and procedures underpinning our electoral process–this is actually a way to minimize the influence of minorities and the lower classes, and to truly keep the will of the people at bay.