On two separate occasions, Victor Lustig posed as a French official, claimed that the government planned to sell the Eiffel Tower for scrap metal to the highest bidder, and accepted hefty bribes from men who wanted to buy it.

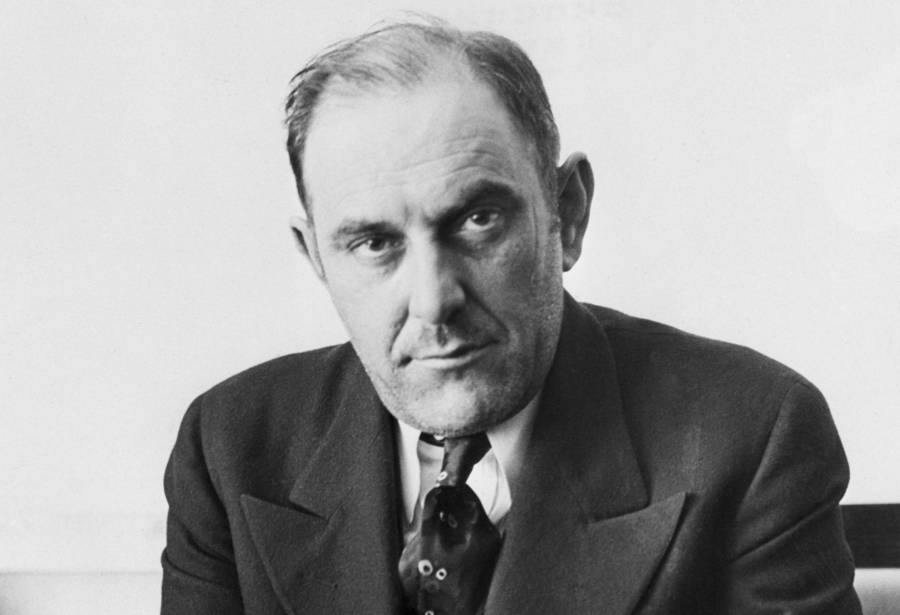

Bettmann/Getty Images“Count” Victor Lustig in 1937, two years after his arrest for running a nationwide counterfeiting operation.

When it came to scams, “Count” Victor Lustig was a professional. The con man from Austria-Hungary had 45 aliases, spoke five languages fluently, and could talk his way out of the stickiest situations.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Lustig traveled across the United States and Europe, swindling anyone who crossed his path. He sought investments for fictional Broadway productions from wealthy passengers on ocean liners, sold a worthless money-duplicating machine to a sheriff in Texas, and purportedly even scammed Al Capone himself.

But his most famous con took place in Paris, where he sold the Eiffel Tower — twice. Lustig posed as a government official and offered the landmark to the highest bidder to sell for scrap metal, then fled after he collected his cash. He was caught the second time he attempted the scam, but that didn’t bring an end to his life of crime.

After dozens of arrests, Victor Lustig was ultimately incarcerated for good in 1935 when authorities uncovered his extensive counterfeiting operation that had pumped more than $2 million in fake cash into the U.S. economy. He spent the rest of his life at Alcatraz, but he went down in history as the “smoothest con man that ever lived.”

The Early Crimes Of Victor Lustig

Born in Austria-Hungary in 1890, Victor Lustig had a turbulent childhood. His parents divorced when he was young, and his father was physically abusive. He once reportedly beat young Victor over the head with a violin.

Accounts of Lustig’s school years vary, but many state that he had dropped out by the time he was 17. Come 1909, he had moved to Paris, started gambling, and received his trademark scar on his left cheek from the angry boyfriend of one of his lovers.

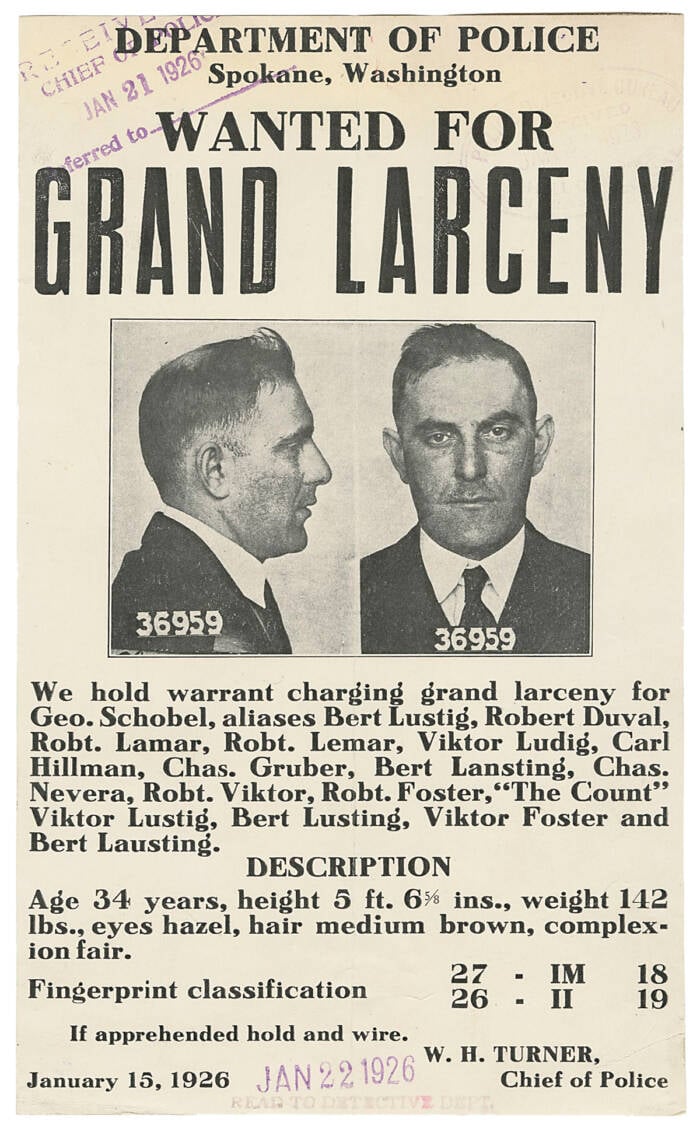

Potter & Potter AuctionsA 1926 poster listing a few of Victor Lustig’s many aliases. He was wanted for grand larceny in Spokane, Washington.

Soon after, his criminal career began. Some of Victor Lustig’s first cons took place on ocean liners traveling between France and New York. While crossing the Atlantic, he pretended to be a producer seeking investments for an upcoming Broadway musical. Wealthy passengers gladly donated to the arts, and Lustig disembarked richer than he’d boarded.

Then, World War I broke out, and ocean travel essentially came to a halt due to the looming threat of U-boats (more than 1,000 people died when the RMS Lusitania sank in May 1915) and the need for vessels to be refitted for military purposes.

So, Lustig changed his tactics. He moved to the U.S. and carried out various cons at banks and other businesses for about a decade. He then returned to Paris in 1925 — and came up with his largest scam yet.

Selling The Eiffel Tower To The Highest Bidder

Upon his arrival in Paris, Victor Lustig read a newspaper article about the expenses involved in maintaining the Eiffel Tower. The city needed money to repaint the massive landmark, and the reporter noted that some citizens would rather see the Eiffel Tower removed than continue paying for it.

With a brilliant con in mind, Lustig hired a forger to create fake government stationery. He then invited several prominent scrap metal dealers to a confidential meeting and introduced himself as the Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs. He related the government’s concerns with the expense of the Eiffel Tower and claimed that there was talk of selling it for scrap to the highest bidder.

Public DomainThe Eiffel Tower in 1927, two years after Victor Lustig “sold” it.

Lustig cautioned the men that they should keep the meeting a secret, as he was worried about the public outcry that would result. All the while, he was keeping an eye out for his target, and he found it in André Poisson.

After the meeting, Lustig met with Poisson individually and made him think that he was a corrupt official. He implied that he would accept a bribe to ensure that Poisson was awarded the contract — and in the end, he fled France with 70,000 francs that Poisson gave him under the table.

After several months, Victor Lustig realized that Poisson hadn’t gone to the police because he was too embarrassed about falling for the scam. So, he returned to France to carry out the same scheme once more. This time, he was caught, so he quickly returned to the U.S. to avoid arrest.

It wasn’t long before he’d come up with yet another con — one that didn’t involve one of the world’s most famous landmarks.

Victor Lustig’s Criminal Career In The U.S.

Back in America, Lustig — who by now had earned the nickname “the Count” — built a “Rumanian Box.” It looked like a small mahogany chest with two slots, and inside was a fake mechanism with levers that did nothing. He tried to sell it to unsuspecting victims as a device that could duplicate any currency, and a sheriff in Texas purportedly fell for the scheme, purchasing the useless box for thousands of dollars.

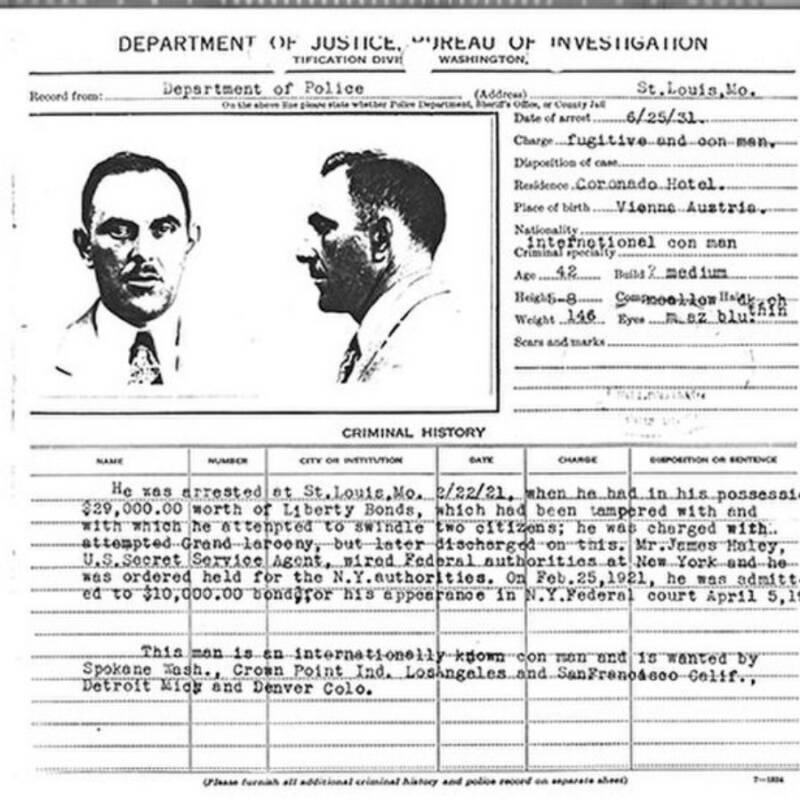

Public DomainA 1931 document from the Bureau of Investigation referring to Victor Lustig as “an internationally known con man.”

During this period, Lustig also seemingly rubbed elbows with underworld figures like Lucky Luciano, Jack “Legs” Diamond, and Arnold Rothstein. This led to his alleged introduction to Al Capone — and one of the riskiest cons of his life.

As the story goes, Victor Lustig gained Capone’s trust by asking him to invest $50,000 in a criminal scheme. He kept the money for several months and then returned it, informing Capone that the deal had fallen through. Capone was impressed that Lustig had been so honest, so when the con man asked for $5,000 to tide him over until another deal worked out, Capone had no problem handing over the cash.

In 1930, Lustig began the scam that would ultimately land him behind bars. He partnered with two men in Nebraska to form a counterfeiting operation that soon spread across the U.S. Within five years, more than $2.3 million in “Lustig money” was circulating, which quickly drew the attention of federal agents.

Public DomainOne of the counterfeit bills printed by Victor Lustig, known as “Lustig money.”

“Count” Lustig’s many aliases and disguises kept him safe for a while — but he couldn’t run from the law forever. Although one Secret Service agent described him as “elusive as a puff of cigarette smoke and as charming as a young girl’s dream,” the police finally tracked him down in 1935. But he still had a few tricks up his sleeve.

The Downfall Of The ‘Smoothest Con Man That Ever Lived’

On May 10, 1935, Victor Lustig was arrested in New York City. The police reportedly found a key on him that opened a locker in a nearby subway station containing $51,000 in counterfeit bills in addition to the plates used to print them. It was an open and shut case.

The day before his trial, however, Lustig vanished from his third-floor prison cell. As reported by The New York Times at the time, he escaped by “knotting sheets together and sliding down them to the street.” He managed to evade arrest for another month, but he was ultimately recaptured in Pittsburgh, reportedly telling the police who found him, “Well, boys, here I am.”

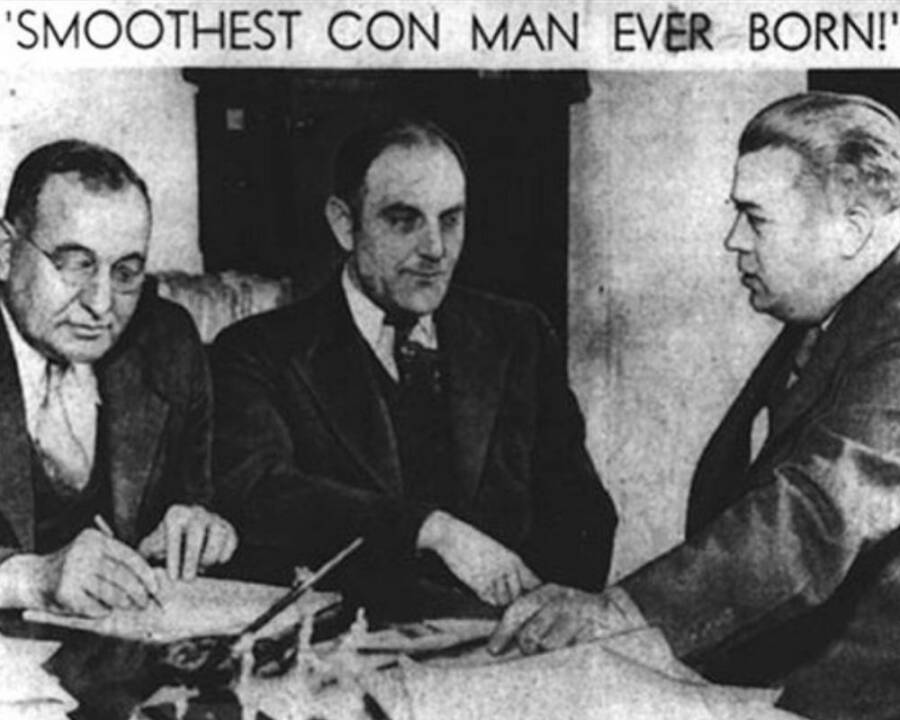

Public DomainA photo from a Philadelphia newspaper showing Victor Lustig being questioned after his 1935 arrest.

This time, Lustig made it to trial, where he was sentenced to 20 years behind bars at Alcatraz. A Secret Service agent at the courthouse allegedly told him, “Count, you’re the smoothest con man that ever lived.”

He remained imprisoned until his death from pneumonia on March 11, 1947, at age 57.

Victor Lustig is best remembered today as the “man who sold the Eiffel Tower,” but he’s also been attributed as the author behind the “10 Commandments for Con Men.” The illicit list includes entries like “Never look bored,” and “Never get drunk,” as well as “Hint at sex talk, but don’t follow it up unless the other fellow shows a strong interest.”

The rules may seem silly — but they made Victor Lustig one of the most notorious con artists in history.

After reading about the life and crimes of Victor Lustig, learn about nine of history’s biggest con artists. Then, discover the true story of Frank Abagnale, the man who inspired Catch Me If You Can.