When Cadwallader Colden Washburn built a mill in Minneapolis in 1874, it was the largest ever constructed. Just four years later, a blast caused by excess flour dust reduced it to rubble.

In May 1878, Minneapolis was booming as the plentiful rivers, streams, and waterfalls running throughout the city powered its rapidly-expanding milling industry. Mills produced timber and flour for millions across the nation as the United States expanded westward and Minneapolis was perfectly positioned to take in 100 boxcars of wheat every day and turn it into high-quality flour.

In the years following the Civil War, technological and scientific breakthroughs were fueling a new age of industrial expansion. Minneapolis quickly became the flour-milling capital of the world, turning itself into the northern-plains metropolis that it is today.

But the growth always comes at a cost, and in 1878, the lives of nearly two dozen mill workers became the price Minneapolis paid after the largest flour mill in the world blew up with such force that it leveled was heard 10 miles away.

A Growing Nation Sparks A Milling Boom

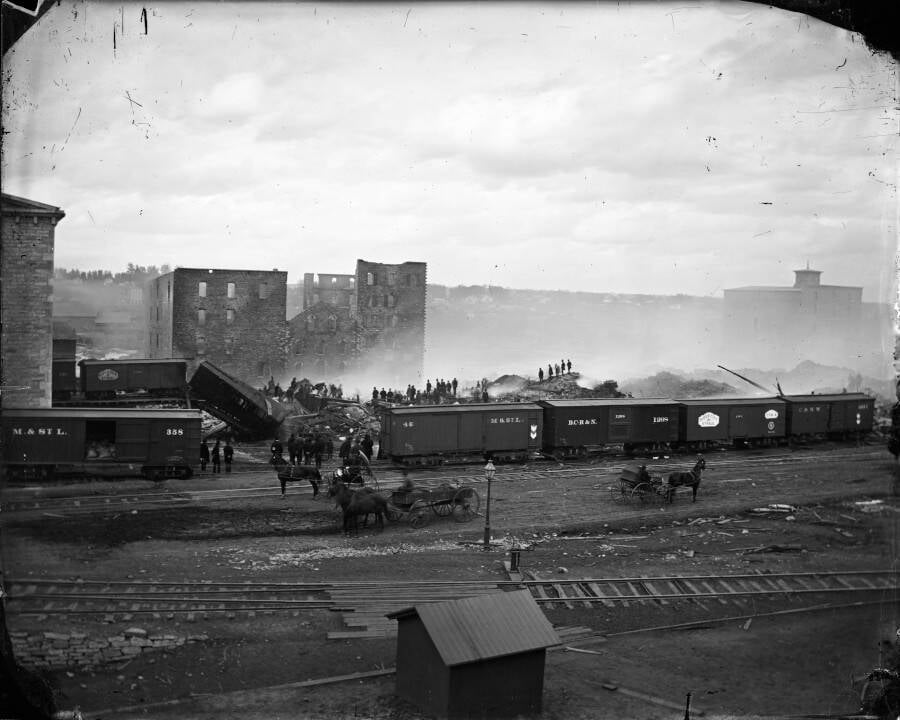

Hennepin County LibraryMinneapolis' Washburn 'A' Mill before its destruction in 1878. The largest mill in the world at the time, it was capable of producing about one-third of the more than one million of pounds of flour milled in Minneapolis every day in the 1870s.

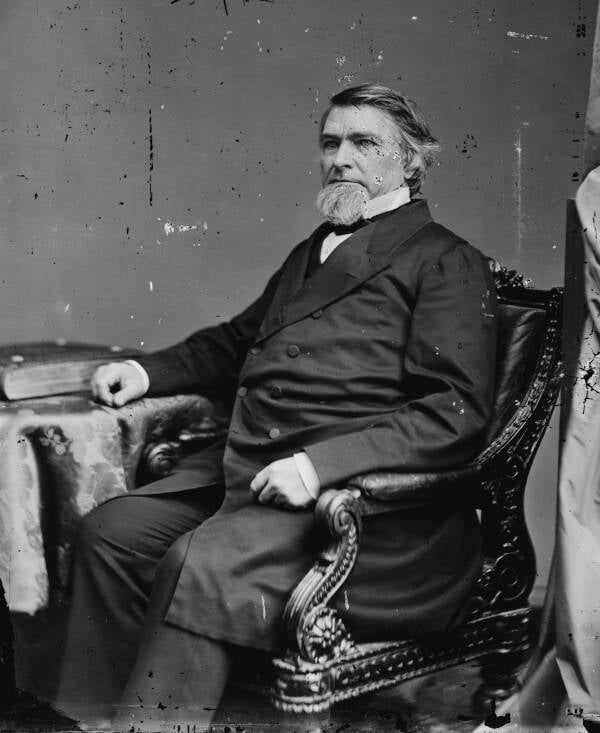

The crown jewel of Minneapolis' flourishing milling district was the gargantuan Washburn 'A' Mill, which produced almost 2,000 barrels of flour daily. Cadwallader Colden Washburn, an industrialist and former Civil War general, built the mill in 1874 over St. Anthony Falls and employed 200 workers in city with a total population of only about 40,000. At the time of its construction, the 'A' Mill was declared the largest in the world.

The Washburn-Crosby company was drawn to the city by its churning waterfalls, which provided cheap and renewable power for the mill to operate. The development of an extensive river and rail network around Minneapolis also made bringing wheat in from the plains and shipping out the processed flower quick and efficient.

But while the city's mills fed its growing population and produced enough surplus to turn huge profits for the industry, milling was not without its dangers. Like any industrial worker of the era, millers risked severe and even fatal injuries from the mill's machinery.

From snapped fan belts that could break bones and cut deeply into a worker's flesh to the gears and mill wheels that could crush any limb that got caught beneath or between them. Deadliest of all were the fires and explosions produced by the friction of the machinery igniting the fine particulates in the air that permeated the entire building.

In an era before safety regulations, most mill owners treated efforts to protect workers as a waste of money at best or as a way to increase profits at the expense of human lives at worst — and it was almost always the latter.

The Explosion at the Washburn 'A' Mill

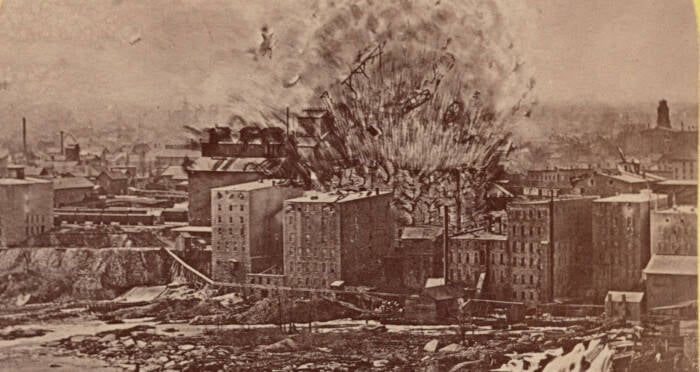

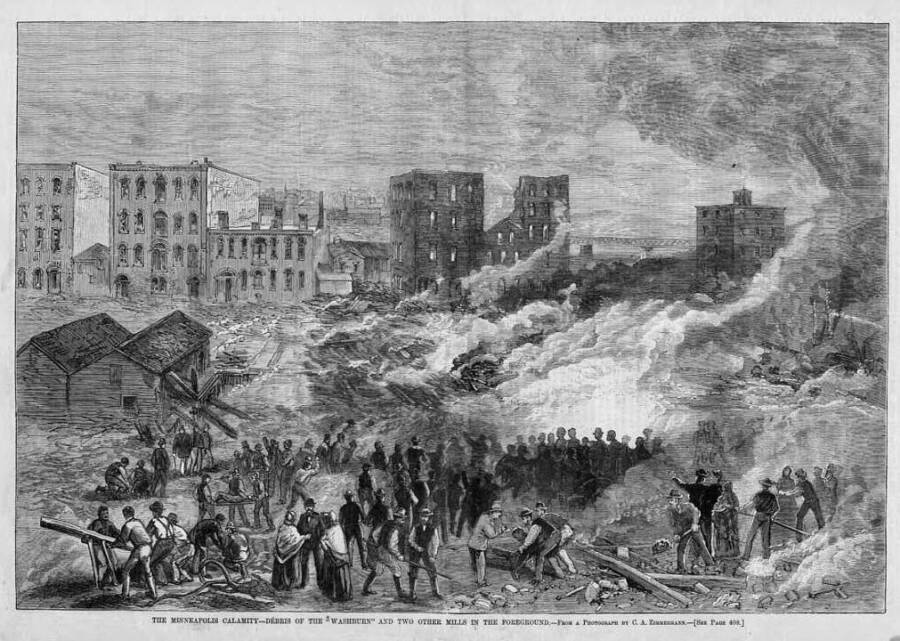

Library of CongressAn artist's representation of the Great Mill Explosion of 1878 that destroyed the Washburn 'A' Mill.

At 6 p.m. on May 2, 1878, the day shift at the 'A' Mill clocked out and was replaced by the skeleton crew for the night shift. A Dutch-American millwright, Ernest Grundman, was part of the day shift, but he was staying late that night. His job was to maintain the mill's machinery, and he was no stranger to the risks of his trade: a promising baseball career had been cut short when he lost parts of two fingers to machinery in 1876.

From his workbench, he would have seen the groaning, overheated mill wheels, the barrels of lard used as a lubricant, and the suction flues used to whisk away the enormous amounts of dust in the air. From where he worked, Grundman saw two of the millstones run dry, sending off a deadly spark. The dust in the flues quickly caught fire and pressure built up rapidly as the burning particulate released expansive gasses, turning the giant flour mill into a powder keg.

Just after 7 pm, three enormous explosions rocked the mill. Shockwaves shot through the surrounding city and the blast was heard as far away as St. Paul, 10 miles to the east.

The explosion killed 14 mill workers instantly, including Grundman who was likely the closest person to the source of the blast. The expanding fireball from the explosion soon set the surrounding buildings alight and the remaining four perished in the resulting inferno.

One eyewitness to the blast said:

"Each floor above the basement became brilliantly illuminated, the light appearing simultaneously at the windows as the stories ignited one above the other. Then the windows bust out, the walls cracked between the windows and fell, and the roof was projected into the air to great height, followed by a cloud of black smoke, through which brilliant flashes resembling lightening passing to and fro."

The Aftermath

As the disaster unfolded, one eyewitness reported:

"A cloud of smoke issued from the dust spouts in the basement of the mill, and there was an odor of burnt bread ... a little flame about as big as a bushel basket darted out of a window in the basement near the canal in front of the mill. Then it sucked back and all was dark. Then there was a large flame and it went flashing up the mill, quivering against the upper windows, reaching quick as lightening to the top of the seventh story. The roof was lifted and there was a loud report, then another and a terrific explosion which then [knocked] the whole building with its walls of stone, six feet thick at the base, to the ground in a mass of ruins."

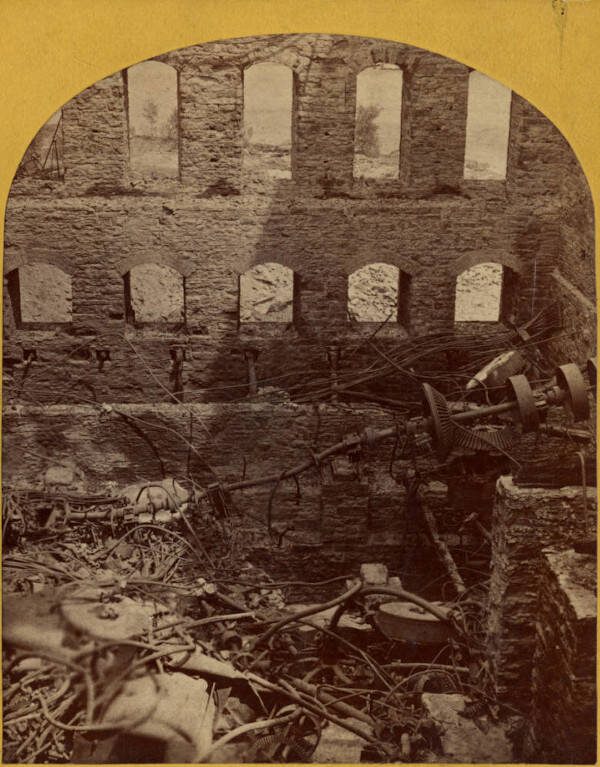

The Scientific American later reported that: "Scarcely one stone stands upon another, as it was laid in big Washburn mill, and the chaotic pile of huge limestone rocks is interwoven with slivered timbers, shafts, and broken machinery."

The New Industrialization of Milling

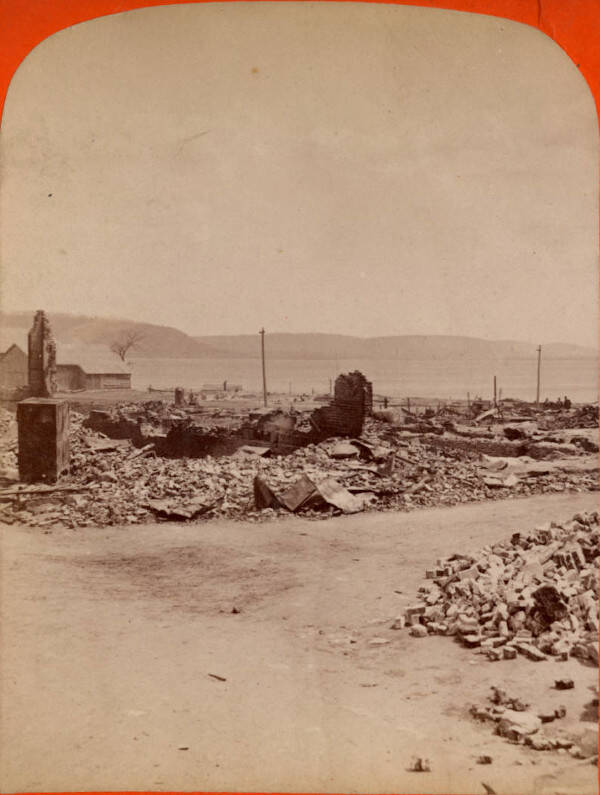

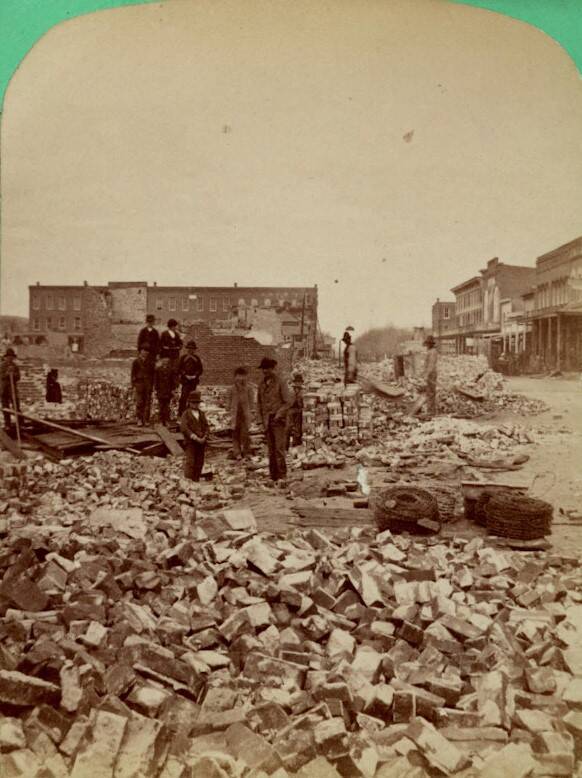

Minneapolis TribuneAn illustration of the aftermath of the Washburn 'A' Mill disaster.

The destruction was so terrible that the fire gutted five nearby mills. Residents were amazed that the entire city wasn't destroyed, having "met with a calamity, the suddenness and horror of which it is difficult to comprehend." The next day, a media frenzy began.

As the news spread, tourists began streaming into town to gawk at the smoldering ruins. Rumors about what had caused the disaster flew thick and fast. People blamed everything from earthquakes to trainloads of nitroglycerine. Some even believed the crackpot idea that the Mississippi River had decomposed into combustible gas.

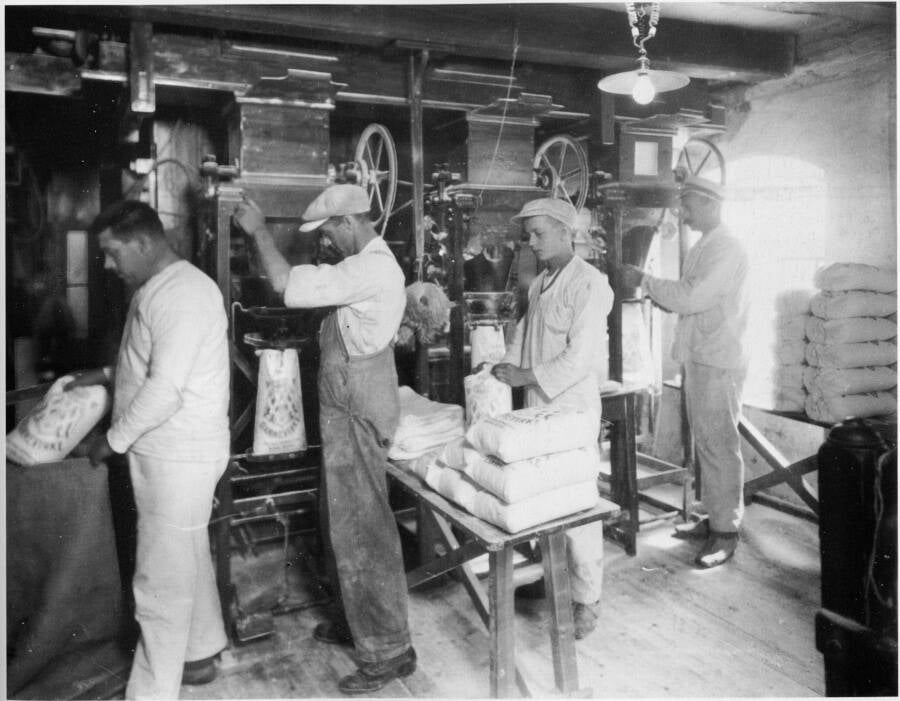

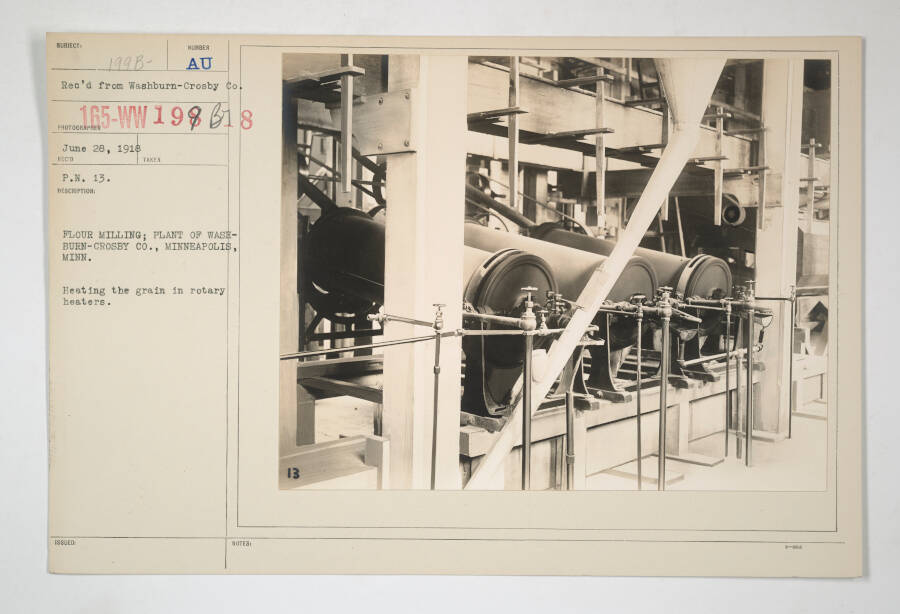

Washburn generously compensated the families of the dead workers, unusual for an industrialist of the time. He then vowed to rebuild the mill bigger and safer than before. He installed cutting-edge dust traps which vastly reduced flammability and, crucially, he replaced the traditional millstones — used since ancient times — with chilled cast iron rollers.

Besides improving the productivity of the milling process, the cast iron was far less likely to spark. Washburn's rebuilt 'A' mill was soon producing 12,000 barrels daily, while his employees were considerably safer.

Minneapolis continued to dominate the flour industry for decades, peaking during the First World War. In 1928, Washburn-Crosby merged with two dozen other companies to form General Mills. Though 18 men lost their lives to a tragic industrial accident, their deaths helped improve the safety of flour mills in the city and beyond.

Now that you've learned about the Washburn mill explosion, find out more about the Halifax Explosion, another tragic industrial disaster. Then, have a look at these images of some of the deadliest disasters of modern history.