On September 13, 1814, British forces attacked Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Upon seeing the American flag flying the next day, Francis Scott Key penned "The Star-Spangled Banner."

As the national anthem of the United States, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is a ubiquitous part of American life. It plays before everything from military ceremonies to football games. But who wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” and why does it matter today?

Even though most Americans know the song, the history behind it remains a mystery to many. Just for starters, the fact that it’s only been America’s national anthem for a fraction of American history might come as a shock.

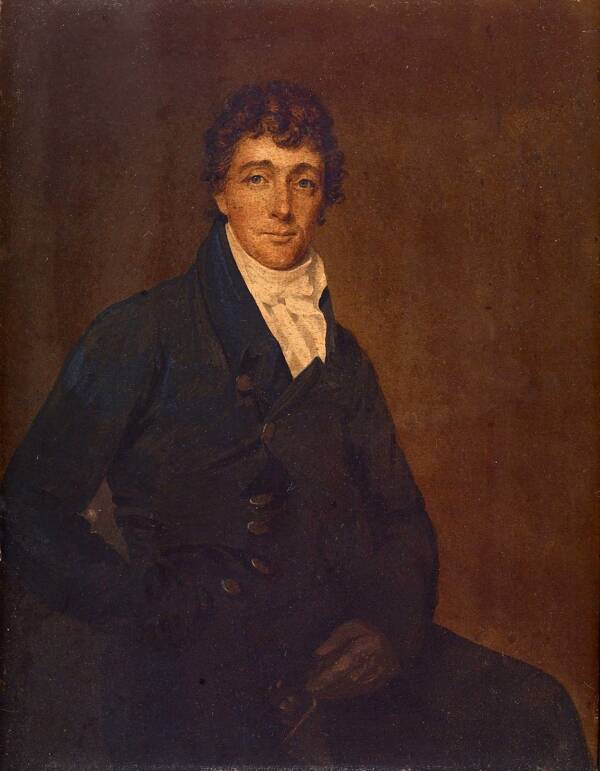

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was penned by Francis Scott Key, a 19th-century lawyer who dabbled in poetry. Inspired by the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, Keys was so moved at the American resilience he saw that he couldn’t wait to write the lyrics — and scribbled them on the backside of a letter.

Despite the instant popularity of the song, it took more than a century after it was written for it to be officially recognized as the national anthem. And ever since its creation, it’s been steeped in controversy, from its racist lyrical content to its anti-British sentiments.

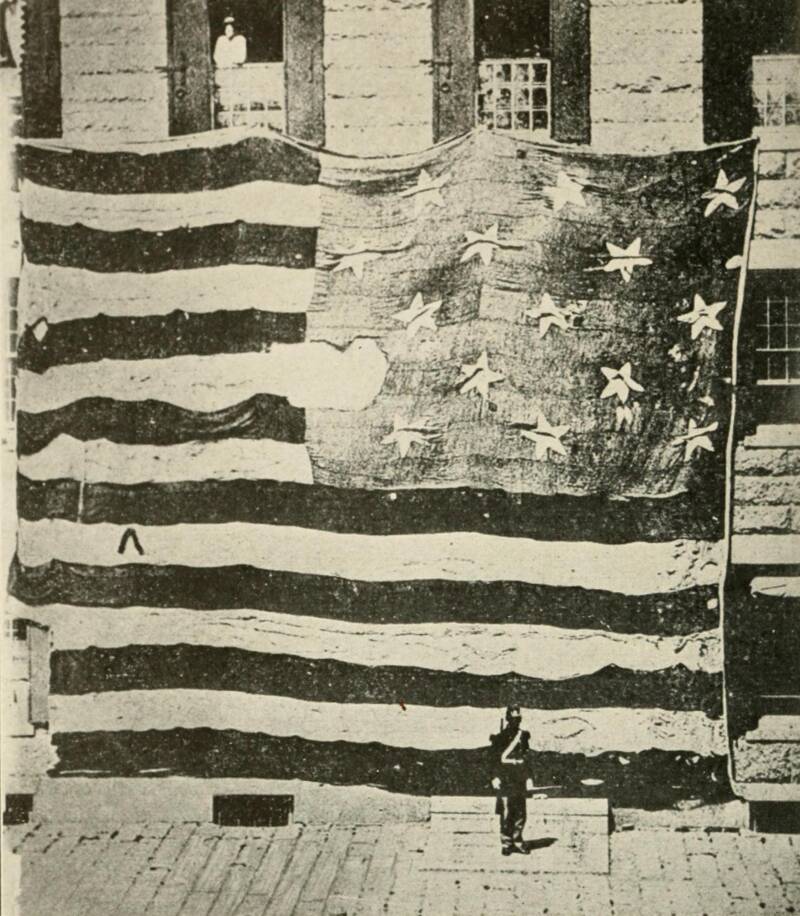

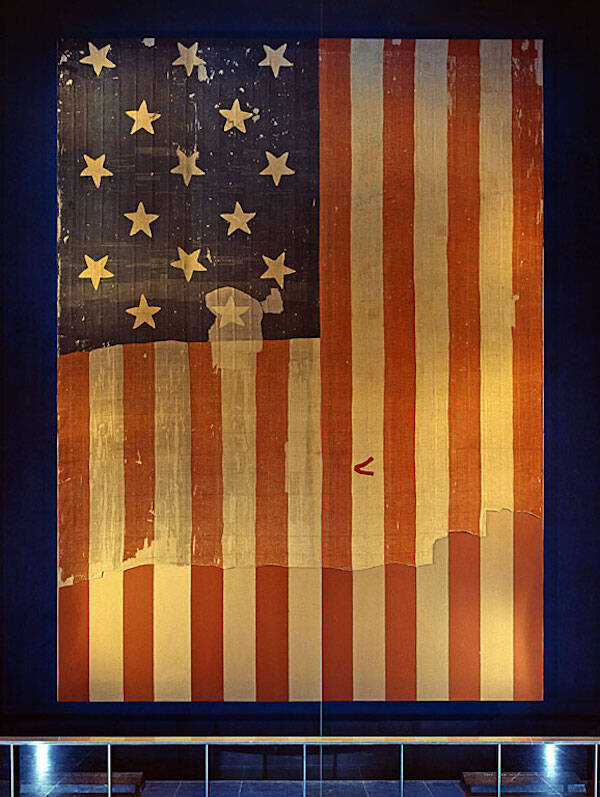

Wikimedia CommonsThe flag that flew over Fort McHenry and inspired the national anthem.

Furthermore, the musical foundation of the song wasn’t even original. It was simply a British tune borrowed out of convenience.

Many Americans have a collectively hazy recollection about the country’s national anthem, but the fact that we usually only sing about one-fourth of the song probably has something to do with it.

Frankly, a thorough examination of the tune is long overdue.

When And Where The National Anthem Was Written

In order to understand why the national anthem was created, it’s imperative to put contemporary political history into context. The War of 1812 was mostly a battle between the United States and the United Kingdom, but France also played a pivotal role in the war’s development.

The war mostly erupted due to British interference with American trade. With Britain impressing U.S. sailors into the British Royal Navy and slowing westward expansion, America declared war in June 1812.

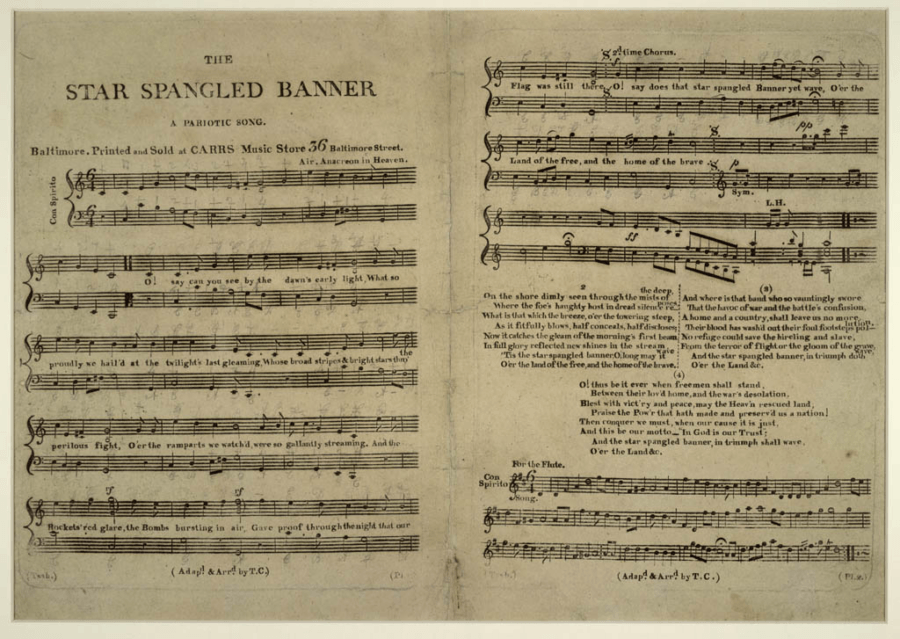

Wikimedia CommonsFrancis Scott Key’s original manuscript of the song, now on display at the Maryland Historical Society.

A little over a decade before this, America had already been in a “Quasi War” with France from 1798 to 1800. This was largely due to the United States refusing to repay its debt to France. Though France had financially supported America during its fight for independence, the U.S. argued this debt had been owed to a previous regime that was now long gone.

The war against Britain in 1812 initially saw America score some promising victories. However, that was largely due to Britain’s separate war with France, which spread its efforts thin.

In 1814, the tide turned towards the other way. British troops not only invaded Washington D.C., but also set the White House on fire. With Baltimore serving as a major seaport, the Royal Navy set course for the city’s harbor in September.

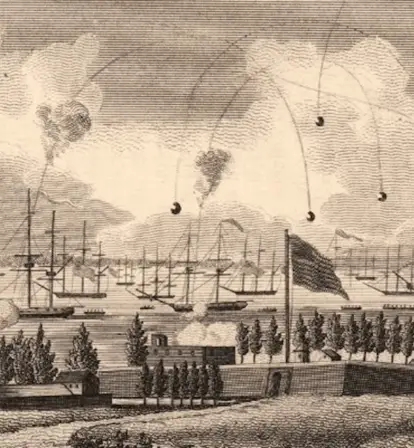

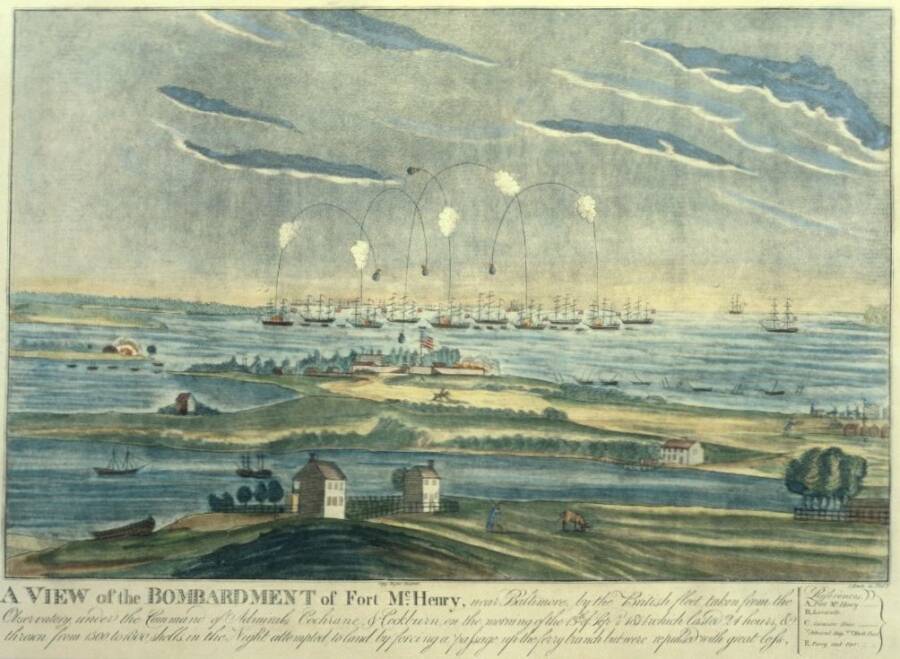

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration of the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

Coincidentally, Maryland lawyer Francis Scott Key would find himself in the very same spot — negotiating a friend’s release after he’d been captured in an earlier battle.

Who Wrote The Star-Spangled Banner?

Key seemed like an unlikely candidate to write a national anthem for his country — especially during wartime. He had previously referred to the war as “abominable” and a “lump of wickedness.” But once he witnessed the Battle of Baltimore, it quickly became a source of inspiration for him.

The British bombardment of Fort McHenry began on a rainy evening on Sept. 13, 1814. From a ship anchored in Baltimore’s harbor, Key witnessed the “bombs bursting in air” above the city.

Wikimedia CommonsFrancis Scott Key was a slaveholder who wrote poetry when he wasn’t working as a lawyer.

When the morning mist dissipated, the outcome became clear. Rather than a Union Jack, Key saw the American flag fluttering in the breeze.

Still aboard the ship, Key finished writing the first verse about the experience on the back side of a letter. He later made his way safely to shore, with his friend in tow.

Key couldn’t have known that he’d be famous more than a century later as the man who wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” — especially since that wasn’t the name he originally gave the song.

He completed his draft of four stanzas in Baltimore, calling it “Defense of Fort M’Henry.” His brother-in-law Joseph Nicholson, who was a commander of a militia at the fort, had the verse printed for public distribution.

Wikimedia CommonsThe song was set to the music of a popular British drinking song written by John Stafford Smith for the Anacreontic Society — a gentlemen’s social club in London — called “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

This reprinting came with a note that the poem should be accompanied by the melody for an English drinking song by John Stafford Smith called “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The boozy anthem was quite popular in the U.S. by then, and had even been used previously by defenders of John Adams for a song called “Adams and Liberty.”

Within days, The Baltimore Patriot reprinted Key’s poem, calling it a “beautiful and animating effusion” destined “long to outlive the impulse which produced it.” Renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner” by November, this song spread across papers nationwide.

How The Song Became The National Anthem Of The United States

While it took more than 100 years for “The Star-Spangled Banner” to become our national anthem, the song was well-received soon after its publication. Played during various events, including Independence Day celebrations and political campaigns, people were rather enamored with the tune.

By the time of the Civil War, members from both sides of the conflict tried to claim the song as their own. For example, The Richmond Examiner editorialized in 1861 that the tune was “Southern in origin, in sentiments, in poetry, and song. In its association with chivalrous deeds, it is ours.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe song officially became America’s national anthem in 1931.

Meanwhile, physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was so eager to claim it for the North that he added a new stanza, which described “the millions unchained who our birthright have gained.” This revised version somehow found its way into schoolbooks in a surprising variety of states like New York, Indiana, and Louisiana in the early 1900s.

As World War I saw Brits and Americans form an alliance, pacifists criticized “The Star-Spangled Banner” for its anti-British roots. Nonetheless, President Woodrow Wilson ordered it to be played at military events. Meanwhile, a group of Columbia University professors tried to organize a contest to find an alternative.

“America the Beautiful” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic” were certainly on its heels, but “The Star-Spangled Banner” made major strides at the end of World War I when it was played at the 1918 World Series game between the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox.

A Maryland native, Congressman John Charles Linthicum began promoting legislation to recognize the song as the national anthem of the country. His attempt on April 15, 1929 did the trick, with a petition of support earning 5 million signatures in 1930. On top of that, more than 150 organizations released endorsements for the song and up to 25 governors sent letters and telegrams in support of the tune.

Wikimedia CommonsThe flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the national anthem at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History and Technology.

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary originally thought the song was too difficult to be sung by common folk. To prove them wrong, Elsie Jorss-Reilley and Grace Evelyn Boudlin sang it to them on January 31, 1930. The Committee voted in favor, sending the bill to a receptive House and Senate.

On March 4, 1931, President Herbert Hoover officially made “The Star-Spangled Banner” the national anthem of the United States.

Revisting The Legacy Of Francis Scott Key

Some people believe that an artist and their art can be separated. But others are disturbed that Francis Scott Key, the man who wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was also a slaveholder. While he reportedly freed seven of his household slaves and wasn’t physically cruel, his authorship of a song about freedom is painfully ironic at best.

On the other hand, Key biographer Marc Leepson explained that Key “strongly opposed international slave trafficking on humanitarian grounds, and defended enslaved people and free blacks without charge in D.C. courts.”

Nonetheless, Key’s own words in “The Star-Spangled Banner” remain a focal point of critique — as his third stanza proclaims, “No refuge could save the hireling and slave, from the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave.”

It remains unclear today exactly what Key meant by those words. Some believe that since he was a slaveholder, he was simply delighting in the fact that his slaves couldn’t escape.

Others think that he was condemning the American slaves who escaped by fighting alongside the British. Yet others are convinced that Key was using the word “slave” as a rhetorical device to describe the Brits themselves.

Regardless of Francis Scott Key’s intentions, these words have angered people for decades — and it’s one of the many reasons why some Americans think it’s time for a new national anthem.

After learning about Francis Scott Key, the man who wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner,” discover who actually wrote the Declaration of Independence. Then, learn about William Levitt and the racist origins of America’s suburbs.