How "Wild Bill" Hickok rose from humble Quaker roots in Illinois to become a legendary lawman and gunslinger of the Wild West.

In the days of the Wild West, no one was cockier than Wild Bill Hickok. The legendary gunfighter and frontier lawman once claimed that he had killed hundreds of men — a truly shocking exaggeration.

It all started with an infamous article that was published in an 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly. The article read, “Wild Bill with his own hands has killed hundreds of men. Of that, I have not a doubt. He shoots to kill.”

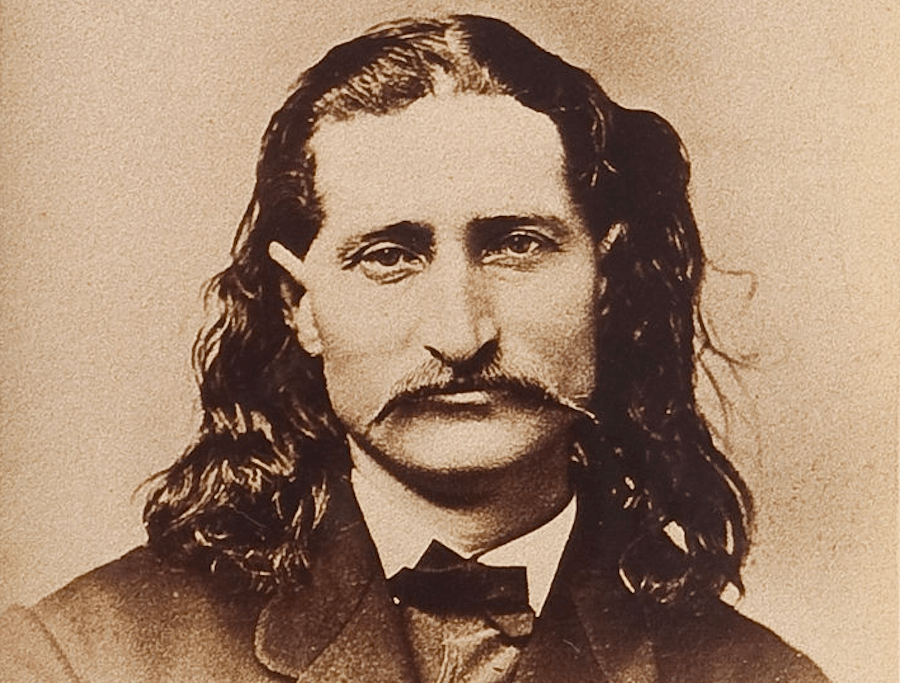

Wikimedia CommonsFrom his life as a frontier lawman to his death in a saloon, the story of Wild Bill Hickok is the stuff of legend.

This article was later credited with turning Wild Bill Hickok into a household name. Hickok soon became a symbol of the Wild West, as he was thought to be a man so feared that people shook whenever he came into town.

In reality, Hickok’s body count was probably far lower than “hundreds.” And to the people who knew him, Hickok wasn’t nearly as fearsome as he seemed on paper. But there’s no doubt that he was a talented gunslinger, and that he was involved in a few famous gunfights. Here’s the truth behind the legend — which endured long after Wild Bill Hickok died.

The Early Years Of James Butler Hickok

Wikimedia CommonsJames Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok before he became a gunslinger. Circa 1860.

James Butler Hickok was born on May 27, 1837, in Troy Grove, Illinois. His parents — William Alonzo and Polly Butler Hickok — were Quakers and antislavery abolitionists. The family participated in the Underground Railroad before the Civil War and even used their home as a station stop.

Sadly, William Alonzo Hickok died when James was just 15 years old. To provide for his large family, the teenager took up hunting. He quickly garnered a reputation for being a meticulous shot at a young age.

It’s believed that because of his pacifist roots — and also because of his steady hand on the pistol — Hickok was able to mold himself into a sort of defender of the bullied and a champion of the oppressed.

At age 18, Hickok left home for Kansas territory, where he joined up with a group of antislavery vigilantes known as “Jayhawkers.” Here, Hickok reportedly met 12-year-old William Cody, who later became the infamous Buffalo Bill. Hickok soon became a bodyguard for General James Henry Lane, a senator from Kansas and a leader of the abolitionist militia.

When the Civil War broke out, Hickok eventually joined up with the Union and acted as a teamster and a spy, but not before he was attacked by a bear on a hunting expedition and forced to sit some of the war out.

While healing from his injuries, Hickok was briefly employed with the Pony Express and cared for the stock at a facility in Rock Creek, Nebraska. It was here, in 1861, where the legend of Wild Bill Hickok first emerged.

A notorious bully named David McCanles had demanded funds from the station manager that he simply did not have. And it’s rumored that at some point during the confrontation, McCanles referred to Hickok as “Duck Bill” because of his pointy nose and protruding lips.

The argument soon escalated into violence, and Hickok allegedly pulled out a gun and shot McCanles dead on the spot. Hickok was brought to trial but acquitted of all charges. Shortly afterward, “Wild Bill Hickok” was born.

How The Legend Of Wild Bill Hickok Took Off

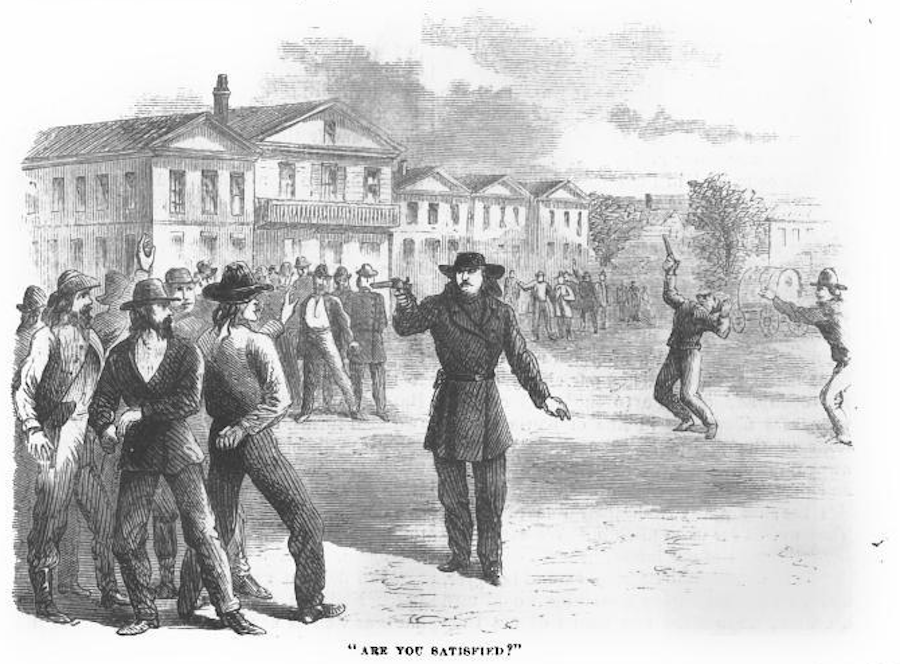

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration from the Harper’s Weekly article that made Wild Bill Hickok a household name. 1867.

To the people of Rock Creek, Nebraska, there was no Wild Bill Hickok — only a soft-voiced, sweet man named James Hickok. It’s believed that David McCanles was the first man that Hickok had ever killed and that it had been in self-defense. Hickok reportedly felt so awful about it that he apologized profusely to McCanles’s widow — and gave her every penny he had on him.

But from that day forward, Hickok would never be the same again. The man that the town thought they knew was dead. His stead there soon became, as one of his neighbors put it, “a drunken, swaggering fellow, who delighted when ‘on a spree’ to frighten nervous men and timid women.”

And after Hickok fully recovered from his hunting injuries, he joined up with the Jayhawkers in the Union Army until the Civil War ended. Around that same time, the marksman picked up a bad habit of gambling — which landed him in a historic duel at the center of town in Springfield, Missouri.

Now called the “original Wild West showdown,” Wild Bill Hickok came face to face with a former Confederate soldier named Davis Tutt. Some believe the two first became enemies over lingering Civil War tensions, while others think they may have been competing for the same woman’s affections.

But either way, what started out as a small argument between the two over a watch and a poker debt somehow escalated into a deadly gunfight — with Hickok emerging victorious. One witness later said, “His ball went through Dave’s heart.” It’s believed to have been history’s first quick-draw duel.

The marksman, a deadly shot, had killed again.

When the reporters came rolling into town, Wild Bill Hickok resolved to craft a new identity for himself as the toughest gunfighter in the Wild West.

A man named George Ward Nichols had caught wind of the quick-draw duel and so resolved to interview the champion in Springfield. Hickok had just been set free by a jury after the Missouri town ruled the duel “a fair fight.”

Nichols wasn’t planning on writing anything more than a short piece on the odd jury ruling. But as he sat down with Wild Bill Hickok and listened to him spin his tales, Nichols became enthralled. Hickok, he knew, was going to be a sensation — regardless of how much of his story was actually true.

Indeed, when the article came out, the people of Rock Creek were shocked. “The first article in Harper for February,” one frontier paper read after the article was published, “should have had its place in the ‘Editor’s Drawer,’ with the other fabricated more or less funnyisms.”

A Short Stint As The Sheriff Of Ellis County

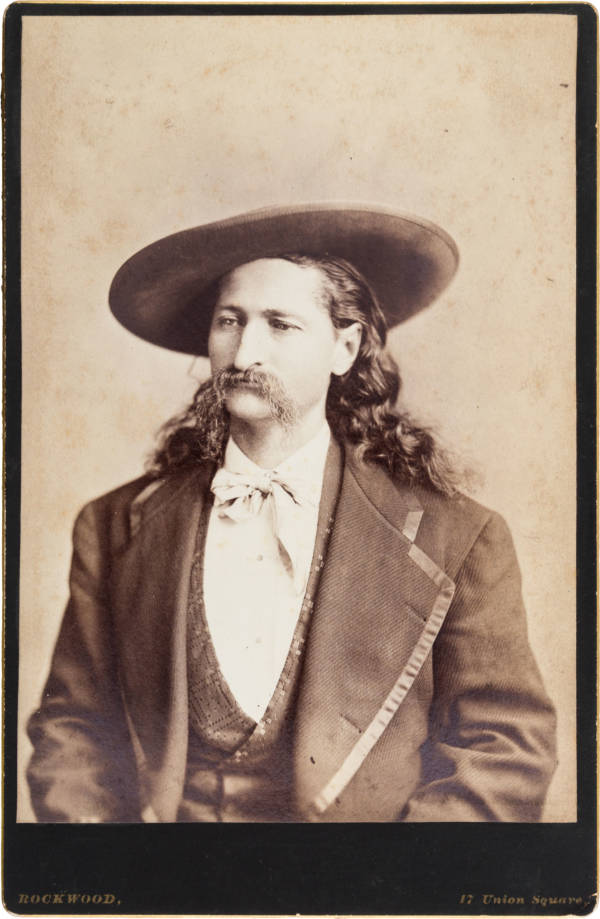

Wikimedia CommonsA cabinet card of Wild Bill Hickok. 1873.

After the duel with Tutt, Hickok met up with his friend Buffalo Bill on tour with General William Tecumseh Sherman. He became a guide for General Hancock’s 1867 campaign against the Cheyenne. While there, he also met Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer, who described Hickok reverently as “one of the most perfect types of physical manhood that I ever saw.”

For a time, Wild Bill Hickok and Buffalo Bill put on outdoor gunslinging demonstrations that featured Native Americans, buffalos, and sometimes monkeys. The shows were ultimately a failure, but they helped contribute to Wild Bill Hickok’s growing reputation in the Wild West.

Ever-traveling, Wild Bill Hickok eventually made his way to Hays, Kansas. There, he was elected the county sheriff of Ellis County. But Hickok killed two men within his first month alone as sheriff — sparking controversy.

The first, town drunk Bill Mulvey, had caused a ruckus about Hickok’s move to the county. In response, Hickok shot a bullet into the back of his brain.

Shortly thereafter, a second man was gunned down by the quick-handed sheriff for talking trash. It’s said that in his 10 months as sheriff, Wild Bill Hickok killed four people before he was finally asked to leave.

The Famed Gunslinger’s Move To Abilene

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Wesley Hardin, another legendary gunfighter of the Wild West.

Wild Bill Hickok next set his sights on Abilene, Kansas, where he served as the town’s marshal. During this time, Abilene had a reputation as a tough town. And it already had a legendary gunfighter of its own — John Wesley Hardin — so tensions were bound to flare between him and Hickok.

It all started when a saloon owner named Phil Coe upset the town by drawing a bull with a massive, erect penis on the wall of his saloon. Wild Bill Hickok made him take it down, and Coe swore revenge.

Coe and his friends tried to hire Hardin to take out Wild Bill Hickok, but he wasn’t too interested in carrying out the murder. However, Hardin went along with the scheme long enough to pull a gun on Hickok.

He made a commotion in the middle of town and, when Wild Bill Hickok came along and told him to hand over his pistols, Hardin pretended to surrender and instead managed to get Hickok at gunpoint.

Hickok, though, just laughed. “You are the gamest and quickest boy I ever saw,” he told Hardin and invited him out for a drink. Hardin was charmed. Instead of killing him, he ended up becoming Hickok’s friend.

The Last Bullet That Wild Bill Hickok Ever Shot

Wikimedia CommonsWild Bill Hickok, near the end of his run as a gunslinger. Circa 1868-1870.

With Hardin refusing to take down Hickok, Coe had no choice but to take him down on his own. Coe put his plan into motion on October 5, 1871.

Coe got a group of cowboys drunk and rowdy enough to fight and allowed them to spill out of his saloon and into the streets, knowing that Wild Bill Hickok would soon come out to see what was happening.

Hickok, of course, did come out. Spotting Coe, he ordered him to hand over his gun before he got involved. Coe tried to pull the gun on him instead, but as soon as the gun started to spin, Wild Bill Hickok shot him dead.

A figure rushed Hickok, and the marshal, who was still keyed up from shooting Coe, turned his gun on the figure and fired.

It was the last bullet that Wild Bill Hickok would ever shoot to kill. For the rest of his life, he would be tortured by the memory of making his way through the crowd to see that the man he’d just shot down was Mike Williams: his deputy, who’d been running over to give him a hand.

How Did Wild Bill Hickok Die?

Wikimedia CommonsCalamity Jane poses in front of Wild Bill Hickok’s grave. Circa 1890.

On August 2, 1876, Wild Bill Hickok died a sudden, violent death while gambling in a saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota. Playing cards with his back to the door, Hickok had no clue that he was about to be murdered.

Jack McCall, a drunk who had lost money to Hickok the day before, stormed in with his pistol, approached Hickok from behind, and shot him dead on the spot. The bullet went through Hickok’s cheek. McCall then tried to shoot others in the saloon, but incredibly, none of his other cartridges worked.

After Wild Bill Hickok died, a pair of aces and a pair of eights were found in his hands. This would later become known as the “dead man’s hand.”

McCall was initially acquitted of the murder, but when he moved to Wyoming and began to brag about how he had taken down Wild Bill Hickok, the county there decided to retry him again. Hickok’s killer was ultimately found guilty, hanged, and buried with the noose still around his neck.

The Wild West lost a legendary figure after Wild Bill Hickok died — even if his background was mostly based on legend. Thanks to his own tall tales, Hickok’s earlier life as a soft-spoken peace-keeper was nearly lost to history. But it seems, even in outlaw country, the truth reigns supreme.

After this look at Wild Bill Hickok, learn about Annie Oakley, the Wild West’s greatest sharpshooter. Then, check out these photos of the real Wild West.