The German vessel Wilhelm Gustloff was carrying up to 10,000 military personnel and civilians across the Baltic Sea when it was attacked by a Soviet submarine on January 30, 1945.

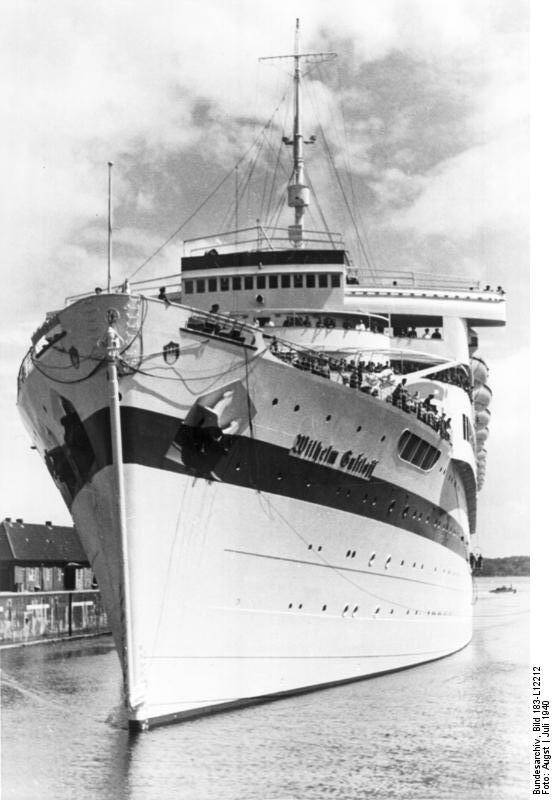

Wikimedia CommonsThe Wilhelm Gustloff in 1939.

As the tides of World War II began to turn against Nazi Germany, its people began to worry. Stories of Soviet revenge had spread among the populace, and as the Red Army encroached upon German territory, some Nazi officials began to share their people’s fears.

In January 1945, they launched Operation Hannibal, a mass naval evacuation of German military personnel and civilians from the ports of East Prussia, which were in the direct path of the approaching Soviets.

Every available ship was called for the operation, including ships like the MV Wilhelm Gustloff, which had been used as a hospital ship and barracks for much of the war. Regardless, the ship began sailing in the Baltic Sea with a mix of German military personnel and civilians on Jan. 30, 1945, in the hopes of taking the people aboard to relative safety elsewhere in Germany.

The ship — originally a cruise vessel for Adolf Hitler’s “Strength through Joy” program — was only designed to carry around a few thousand people. It left port with at least 7,000 people on board, and possibly as many as 10,000. Notably, about half of the passengers on the ship were children.

The same day the vessel took off, it crossed paths with the Soviet submarine S-13, which promptly launched torpedoes at the fleeing ship. This caused it to sink in just one hour — taking at least 6,000 people with it. Some estimates state that as many as 9,000 people perished.

The sinking was the worst maritime disaster in history, with a loss of human life at least four times bigger than that of the Titanic. Yet, in the wake of World War II — and an understandable lack of sympathy for the Nazis — its story was largely ignored or forgotten for decades.

The Wilhelm Gustloff’s Pre-War Service As A Nazi Cruise Ship And Propaganda Tool

The History Collection/AlamyWomen giving the Nazi salute aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff.

Before the outbreak of World War II, the Wilhelm Gustloff was built not as a combat or medical vessel, but as a cruise ship for the Nazi organization Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy). Passengers were carefully selected by the Nazi Party, and there was one large cabin on board that was specifically reserved for Adolf Hitler whenever he wanted to take a trip on the vessel.

As the Royal Museums Greenwich notes, the German ocean liner was actually supposed to be called the Adolf Hitler, but that changed after the assassination of the prominent Swiss Nazi Wilhelm Gustloff. Hitler then decided to name the ship after Gustloff instead.

First launched in 1937, the Wilhelm Gustloff served as an ocean getaway for German workers approved by Nazi officials, featuring cruises that boasted numerous recreational activities. During this time, it was also essentially a propaganda tool. In 1938, for example, the ship carried Austrians on a trip, with the hope that their pleasant experience would encourage them to support the annexation of Austria by Germany.

It even functioned as a polling place in international waters, where Germans and Austrians residing in England could vote on the annexation process. It just so happened, along the way, to rescue 19 British seamen on a sinking vessel, which helped promote a positive image of the Third Reich, as Hitler intended. That said, voting on a cruise ship was a highly unusual move.

Members of the British Parliament noted this, but it was within British law that foreign citizens living in England could vote outside of British jurisdiction. Still, that didn’t write off how unprecedented such a move was. Hindsight, of course, tells us it was an indicator of worse things to come.

Wikimedia CommonsAustrian citizens gathering to hear Adolf Hitler’s imminent declaration of annexation in 1938.

“Is it not without precedent for a foreign government to send a ship into the territorial waters of another country for the purpose of a plebiscite,” asked cabinet member Samuel Hoare at the time, “and does it not constitute a most objectionable form of propaganda, having regard to the circumstances which have led to it?”

Objectionable or not, the propaganda seemed to work. Nearly 2,000 German and Austrian nationals living in England visited the Wilhelm Gustloff to vote, and they overwhelmingly voted in favor of the annexation of Austria. According to The New World, 99.73 percent of those passengers voted for it.

The Wilhelm Gustloff left for Hamburg just days later and continued operating as a civilian ship for the remainder of 1938. By the spring of 1939, however, it — and countless other German ships — were redesigned for war.

The Ship’s Wartime Service And Use As An Evacuation Vessel

Although the Wilhelm Gustloff was initially tasked with transporting the Condor Legion back to Germany after the Spanish Civil War, it was soon set up as a hospital ship for World War II — one that was largely stationary, as well, because it had not been maintained in seaworthy condition.

Along with serving as a place where injured soldiers could be treated, the vessel was also used as barracks. But the ship could not stay docked forever — and the Germans living in East Prussia would soon need to leave as well.

As an Allied victory gradually became more and more apparent and the Soviets closed in on East Prussia, Germany launched Operation Hannibal, an evacuation effort meant to ferry German civilians, soldiers, and equipment across the Baltic Sea, in January 1945. By then, word had spread of the acts of vengeance carried out by Soviet soldiers. They were said to rape or murder any Germans they came across, even if they were civilians, and in the ensuing panic, Germans in East Prussia fled to the shorelines in droves.

Wikimedia CommonsWounded soldiers being treated aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff.

Before long, Hitler sensed the end approaching as well. On Jan. 30, 1945, with the Red Army nearing his doorstep, the Nazi dictator publicly urged that it was up to every German “to do his duty to the last.”

Many Germans in East Prussia believed that other parts of German territory would not be breached. They still felt the Third Reich was strong. Despite Hitler’s urging and the winter weather conditions making travel difficult, they desperately wanted to escape the approaching Red Army.

And so, thousands and thousands of people quickly gathered at ports along the Baltic Sea in the hopes they would be granted passage to safety. But only so many people could fit on the ships at a time.

Even after Admiral Karl Dönitz issued the order to double capacity on all the ships in the fleet — prioritizing the women, children, and elderly — they could still only ferry roughly 30,000 people at a time to start. Of that 30,000, those who had been granted passage aboard the famed Wilhelm Gustloff had considered themselves the luckiest of all.

They were sorely mistaken.

The Deadly Sinking Of The Wilhelm Gustloff

Wikimedia CommonsThe Wilhelm Gustloff was carrying well over its capacity of passengers when it was attacked, sank, and became a wreck on the ocean floor.

Packed to the brim, the Wilhelm Gustloff set off in the Baltic Sea after noon on January 30th, with its precise destination uncertain. While leaving port, Captain Friedrich Petersen anxiously awaited orders of where exactly to land.

The vessel was overcrowded, well beyond its capacity, with anywhere from 7,000 to 10,000 people on board. Passengers on the deck were freezing in the bitterly cold air. Below deck, it reeked of urine, vomit, and sweat. Weather conditions had made it difficult for the crew to get a clear view of the sea before them. And even though Petersen was the ship’s captain, three other captains were on board, each offering his own suggestion for how to proceed.

Petersen was also, notably, less experienced than others on board when it came to warfare. He was advised to sail forward with the ship’s lights off in the shallow waters near the coast, but Petersen, worried about sea mines, instead chose to proceed through deeper waters that had already been checked. He also kept the lights on, fearing a potential collision.

These choices would cost him dearly.

Wikimedia CommonsEvacuation boats crossing the Baltic Sea during Operation Hannibal.

Unknown to Petersen — though perhaps clear to the more seasoned captains aboard — Soviet submarines were patrolling the waters looking for German vessels. One such submarine, the S-13, under the command of Alexander Marinesko, had been out in the waters hoping to find an enemy vessel. In fact, Marinesko needed it. His superiors looked down on him for his problems with addiction, and he was even under threat of court martial.

Then, he saw bright lights on the horizon. The ship that loomed before him was huge — even larger than a typical battleship. He figured it must have been some mighty force or secret weapon. Whatever it was, Marinesko likely assumed that taking it down would be his greatest achievement.

As the submarine silently approached the ship, the passengers aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff were unaware of the danger. Around 9 p.m. — hours after the German vessel departed — the S-13 hit the ship with three torpedoes.

One torpedo ended up striking the crew quarters, killing many people on board who were best prepared to handle such an emergency.

Wikimedia CommonsA Vladimir Kosov painting depicting the destruction of the Wilhelm Gustloff, before it became a wreck on the ocean floor.

As sea water flooded the vessel, passengers flew into a desperate panic.

“The ship is lurching, with almost indescribable noise, and I wonder if the end is near,” recounted one survivor, Hans Rittner. “… There is the smell of carbon dioxide gas in the air, probably from the ship’s fire extinguishers. My lungs burn. We are choking in the dark as the Gustloff plunges lower.”

Within one hour, the Wilhelm Gustloff fell into a watery grave, carrying at least 6,000 and up to 9,000 people down with the wreck. The exact number of victims will probably never be determined, as the estimated total number of people on the ship varies widely. Only 1,239 people were confirmed to have survived the disaster after being picked up by rescue vessels.

Wikimedia CommonsA porthole from Wilhelm Gustloff, salvaged after the wreck was discovered.

While the Wilhelm Gustloff had actually been carrying enough lifeboats and rafts to save 5,000 people on board, most of the lifesaving equipment had frozen to the deck in the cold weather, rendering it useless.

No maritime disaster — not the Titanic, nor the Lusitania — claimed as many lives as the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff.

But despite the harrowing nature of the sinking and the great loss of life, the story of the Wilhelm Gustloff is often overlooked. Perhaps people found it hard to sympathize with the Germans, given the atrocities of the Holocaust. Still, the many children aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff were not responsible for those horrific crimes against humanity — and the youngest among them probably weren’t even aware of them.

Considering the high amount of civilian deaths, some have questioned whether the sinking was a war crime, but it was never declared as such. After all, Marinesko would have had no way of knowing that he was technically targeting a refugee ship, and there were at least 1,000 naval personnel on board, meaning it could easily be viewed as a military target.

Today, the Wilhelm Gustloff wreck sits at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, about 20 miles off the coast of Łeba, Poland. Though some objects have been recovered from the site, most people are prohibited from diving near the doomed vessel. The Wilhelm Gustloff wreck is considered a war grave, and many officials are firm in their stance that the remains of the fallen passengers and crew members should rest peacefully in the ruins.

After reading about history’s deadliest maritime disaster, see our collection of rare Titanic photos from before and after the sinking. Then, read about more of history’s famous shipwrecks.