Even after U.S. Army Lt. William Calley helped perpetrate the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War, most Americans supported him and he faced little punishment for his crimes.

William Calley combed his hair. He ate scrambled eggs and creamed hamburger. Then, he grabbed his ammunition, his rifle, and his cartridge belt and set off for the tiny farming hamlet of My Lai in Vietnam.

It was March 16, 1968. A year and a half later, Calley would be charged, court-martialed, and sentenced to life in prison for what became known as the My Lai Massacre.

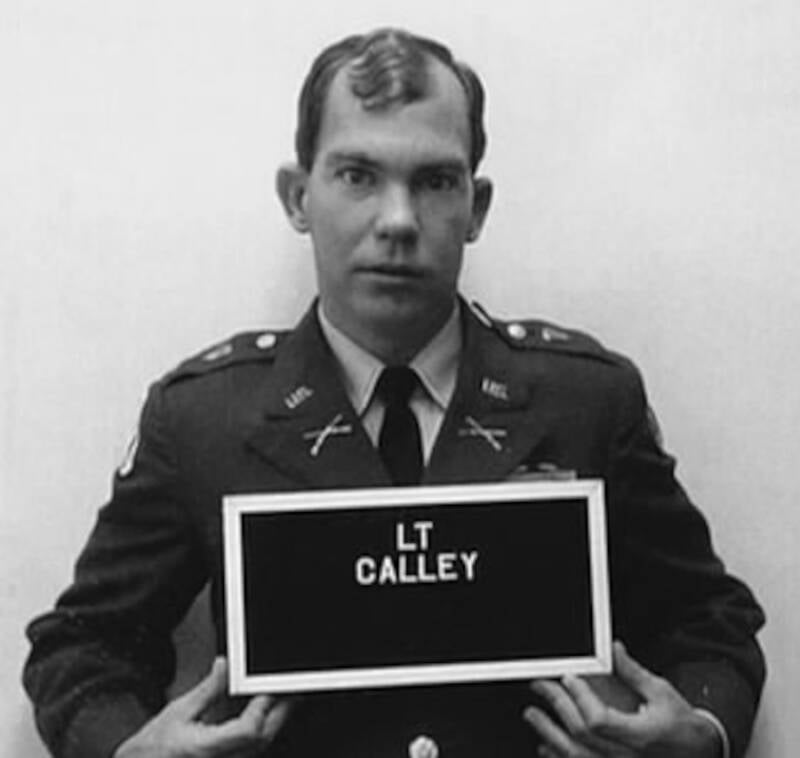

Wikimedia CommonsLieutenant William Calley’s mugshot in 1969.

Although the U.S. Army tried to conceal the truth, it later came tumbling out: Calley and his men had systematically murdered between 300 and 500 innocent Vietnamese civilians and burned their village to the ground.

This is the story of William Calley, the only soldier charged for the My Lai Massacre.

William Calley’s Strange Path To My Lai

William Calley was born in June 1943 in Miami. The son of a World War II veteran, Calley seemed ambivalent about following in his father’s military footsteps. He went to military academies because he’d dropped out of high school. When Calley tried to join the Army in 1964, he was rejected.

But the war in Vietnam drew Calley to the military like a magnet. Upon hearing that the draft board was looking for him, Calley enlisted.

Despite graduating near the bottom of his class at Officer Candidate School (OCS), Calley deployed to Vietnam on Dec. 1, 1967, as a member of the 11th Light Infantry Brigade and a platoon leader in Charlie Company.

U.S. Information AgencySoldiers of the Vietnam Army run across mushy terrain, guns at the ready. Circa 1961.

He was going to Quảng Ngãi Province to fight the National Liberation Front — better known as the Viet Cong.

The fact that he’d ever received a commission was a shock to many. One of the riflemen in his platoon later remarked: “I wonder how he got through [OCS]. He couldn’t read no darn map and a compass would confuse his ass.”

William Calley later described his training as intense and lacking in nuance.

“Nobody said, ‘Now, there will be innocent civilians there,'” Calley wrote in his memoir, Lieutenant Calley: His Own Story. “It was drummed into us, ‘Be sharp! On guard! As soon as you think these people won’t kill you, ZAP! In combat, you haven’t friends! You have enemies!’ Over and over at OCS we heard this and I told myself, I’ll act as if I’m never secure. As if everyone in Vietnam would do me in. As if everyone’s bad.”

After an uneventful couple of weeks, Charlie Company was attached to Task Force Barker, named after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Barker.

Barker had orders to seek out and destroy the Viet Cong 48th Local Force Battalion. The 48th was an unusually effective — and maddeningly elusive — unit. Throughout February 1968 and into March, their booby traps and mines terrorized American forces.

In mid-March, it seemed that Charlie Company might finally have a chance to strike back.

Inside The Horrors Of The My Lai Massacre

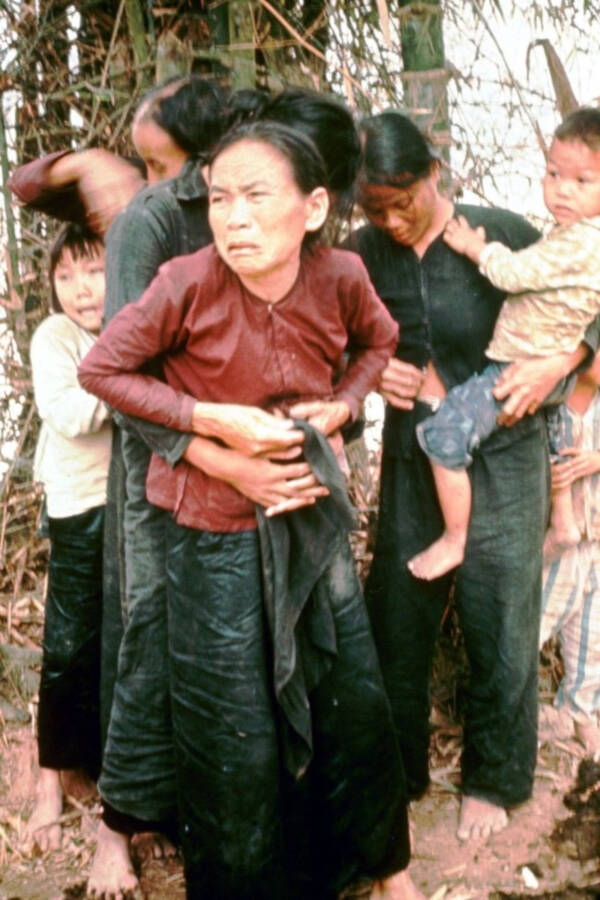

Wikimedia CommonsRonald Haeberle’s photos would become worldwide symbols of the brutality of the Vietnam War.

At a meeting on March 15th, Charlie Company commander Captain Ernest Medina told his men they’d finally have a chance to crush the 48th Local Force Battalion in My Lai, a tiny Vietnamese hamlet.

Medina encouraged his men to be aggressive. He warned them that they would be outnumbered 2-to-1. And he added a revenge element — the day before, a popular member of Charlie Company had been killed by the 48th.

Don’t worry, Medina assured the soldiers, William Calley included. The targets would be “all V.C.’s [Viet Cong’s].” When asked to clarify who the enemy would be, he said that the enemy was “anybody that was running from us, hiding from us, or who appeared to us to be the enemy.”

Medina later testified that Lieutenant Colonel Frank Barker had ordered him to: “Burn and destroy the village; to destroy any livestock, water buffalo, pigs, chickens; and to close any wells that we might find… ”

Library of Congress/Wikimedia CommonsPrivate First Class Nicholas Capezza, seen here setting fire to dwellings in My Lai, later claimed that he saw nothing out of the ordinary that day.

The next morning, William Calley and other members of Charlie Company set out for My Lai by helicopter. They started shooting even before the helicopters had landed.

“Everyone moved into My Lai firing automatic,” Calley later wrote. “And went rapidly, and the GIs shot people rapidly. Or grenaded them. Or just bayoneted them: to stab, to throw someone aside, to go on.”

If the soldiers had stopped for a moment they might have seen that the village was not a bastion for the 48th unit. Instead, it was full of villagers — men, women, and children, many huddled around early morning fires as they made breakfast.

Nguyen Thi Doc, a survivor, was preparing a meal with a dozen family members when she heard the helicopters buzzing overhead.

“[Americans] had been in the village before,” she said. “[They] always brought us medicine or candy for the children. If we had known what they came for this time, we could have fled.”

Instead, she was rounded up with her family, including nine grandchildren, and taken to a field. Then, the soldiers started shooting.

The soldiers tore through the tiny hamlet, killing civilians, raping women, and mowing down anyone who moved with M-16s. They continued to shoot, even as the villagers offered up no resistance.

One soldier, who later died by suicide, recalled that: “I cut their throats, cut off their hands, cut out their tongue, their hair, scalped them. I did it. A lot of people were doing it, and I just followed. I lost all sense of direction.”

At one point William Calley herded a group of villagers into a ditch for execution. A two-year-old boy attempted to crawl out. Calley “picked the boy up, threw him back in, and then shot him.”

By the end of the massacre, hundreds of innocent civilians were dead.

How The U.S. Army Swept My Lai Under The Rug

Wikimedia CommonsAs his troops moved through My Lai, William Calley left a trail of horrific destruction.

The massacre didn’t happen in a vacuum. It didn’t go unnoticed — and it didn’t fail to horrify other soldiers who bore witness to it.

Helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson saw what was happening and tried to intervene. He confronted Calley, who blew him off. “Look Thompson,” Calley said. “This is my show. I’m in charge here. It ain’t your concern.”

As a group of women and children cowered before Calley, Thompson insisted that he back off. “The only way you’ll get them out is with a hand grenade,” Calley said. But Thomspon was able to ferry people to safety.

Thompson reported what he had seen. But the U.S. Army portrayed the massacre as a victory over the Viet Cong. Twenty civilians, the initial investigation reported, had been caught in the crossfire. In other words — move along. Nothing to see here.

But those who knew about the massacre couldn’t forget it so easily. A helicopter gunner named Ronald Ridenhour heard stories from the soldiers who were there.

Ridenhour sent letters to dozen of members of Congress, the State Department, the Defense Department, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He specifically mentioned a soldier named “Kally” who had used his machine gun to massacre civilians.

Ridenhour’s letters prompted a military investigation. Soldiers admitted the truth about what had happened. “We [wiped] out the whole village,” one said. Damningly, a military photographer named Ronald Haeberle even had photos of the aftermath.

Wikimedia CommonsSergeant Ronald Haeberle, seen in the reflection above the man’s body in the well, took photographs of the massacre.

As a result, Calley was charged with the premeditated murder of 109 people. But the military obscured the facts of the case. “An Army officer has been charged with murder in the deaths of an unspecified number of civilians in Vietnam in 1968,” the New York Times reported — on Page 14.

It took an investigative journalist named Seymour Hersh to unravel the rest of it. Incredibly, even after Hersh had discovered that Calley was charged with 109 murders, major publications passed on the story. He brought the scoop to the Dispatch News Service, a small, antiwar outlet in D.C.

On Nov. 12, 1969, the story broke — and spread like wildlife through a country already agitated by a swelling antiwar movement.

William Caley And The Uncomfortable Legacy Of A Wartime Massacre

Wikimedia CommonsA monument to the massacre at My Lai.

Multiple other soldiers were tried for participating in or trying to cover up the massacre. None were punished. Only William Calley, on March 29, 1971, was found guilty. He was charged with the premeditated murder of at least 22 Vietnamese civilians.

Remarkably, Calley’s conviction was not met with roaring approval from the American public. A 1971 Gallup poll found that 79 percent of Americans, pro- and anti-war alike, felt Calley had been unfairly sentenced.

Tens of thousands of people wrote Calley letters of support. The public pressured the White House to give Calley a pardon. Politicians, sensing the direction of the wind, piled on as well. Governor Jimmy Carter urged his fellow Georgians to “honor the flag as [William Calley] had done.”

A song written in Calley’s honor sold hundreds of thousands of copies. It went:

“My name is William Calley, I’m a soldier of this land

I’ve tried to do my duty and to gain the upper hand

But they’ve made me out a villain, they have stamped me with a brand

As we go marching on

I’m just another soldier from the shores of U.S.A.

Forgotten on the battlefield 10,000 miles away.”

President Richard Nixon had initially called the My Lai massacre “abhorrent to the conscience of all the American people.” But he too changed his tune to align with public sentiment. He reduced William Calley’s sentence to house arrest.

Calley’s term was cut from life to twenty years, then from twenty years to ten. Calley served only three and a half before he walked free.

William Calley kept out of the public eye until 2009, when he finally apologized for his actions at a Kiwanis Club meeting in Columbus, Georgia, stating:

“There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai. I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

A scapegoat, a murderer, or all of the above? However William Calley is remembered, one thing is for certain. His name will always be tied to My Lai, that tiny hamlet in Vietnam, and the day he summoned hell on Earth.

After reading about William Calley, take a closer look at the shocking reality of the Vietnam War in these declassified photos. Then, check out these 27 facts about the Vietnam War that you never learned in school.