Wilmer McLean moved his family 100 miles south after the first battle of the Civil War broke out in his yard — but through a strange twist of fate, Robert E. Lee would surrender to Ulysses S. Grant in McLean's new parlor.

Library of CongressWilmer McLean and his family on the front porch of their house in Appomattox in 1865.

Wilmer McLean holds a strange spot in American history. In an odd twist of fate, the Civil War began in his backyard and ended in his parlor.

The swelling tensions between North and South burst into violence near McLean’s farmhouse in Manassas, Virginia in 1861. Soon afterward, McLean and his family fled.

But they couldn’t outrun the conflict. Union and Confederate forces descended upon McLean once more in 1865. This time, they wanted to make peace. Finally, Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at McLean’s house in Appomattox, ending four years of bloody fighting.

This is the story of how the Civil War followed Wilmer McLean, an ordinary grocer from Virginia.

Wilmer McLean And The Battle of Bull Run

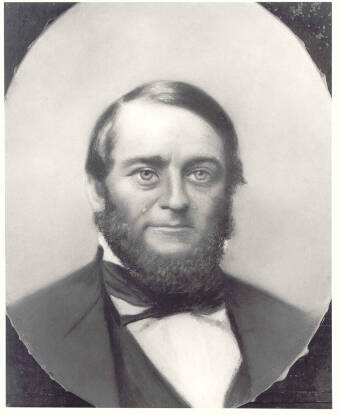

National Park ServiceWilmer McLean was too old to fight in the Civil War, but the war came to him.

By the time the war broke out in 1861, Wilmer McLean had established a quiet, stable life for himself and his family. He had married Virginia Mason, a wealthy widow, in 1853. The couple moved to Mason’s “Yorkshire” plantation in Manassas, Virginia — where a meandering stream called Bull Run cut through their property.

As war loomed, McLean identified with the Confederate cause. At forty-six, he was too old to enlist when the conflict began, but he eagerly gave help to the Confederate troops who soon swarmed the peaceful pastures nearby. Both North and South eyed nearby Manassas Junction, a strategic railroad point, as an important battle prize.

Confederate General P.G.T Beauregard — who commanded the Confederate Army of the Potomac and who had overseen the first shots fired on Fort Sumter — arrived in Manassas in June. Beauregard noted in his report that McLean was among the citizens he encountered who provided valuable information about the area.

McLean did more than provide information. Based on wartime receipts, McLean offered the use of the buildings at Yorkshire to the Confederate troops, including the use of his barn as a military hospital.

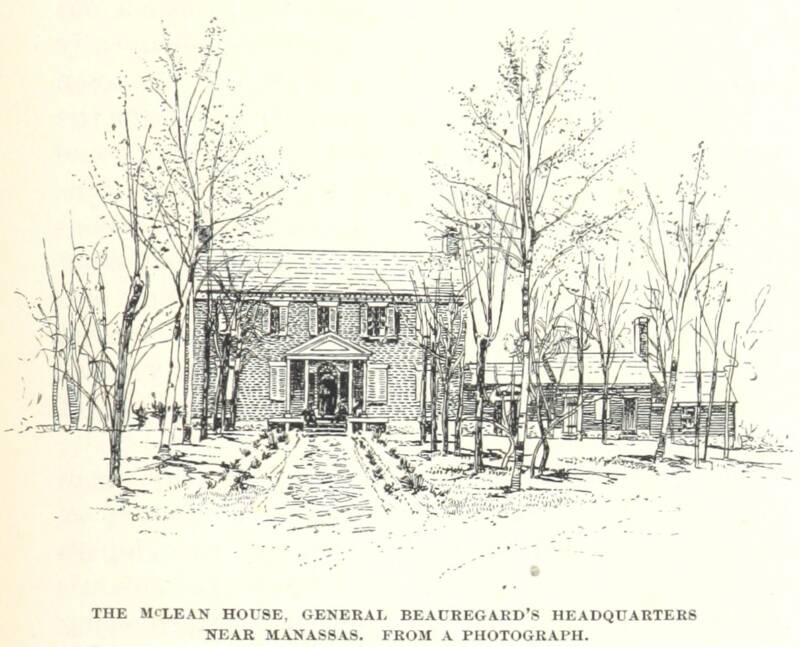

Beauregard praised Wilmer McLean and other Manassas loyalists as “ready to give me their time without stint or reward.” As the battle loomed, McLean moved his family to safety; Beauregard took over their home as his headquarters.

Wikimedia CommonsConfederate forces used Wilmer McLean’s Manassas farm as their headquarters during the First Battle of Bull Run.

The first clash between North and South — called the First Battle of Bull Run by the Union and the First Battle of Manassas by the Confederates — would result in a Confederate victory.

But McLean’s house did not escape unscathed. During the battle, a Union shell smashed through a detached kitchen in the yard, where servants worked to prepare a meal for the troops.

E.P. Alexander, a Confederate soldier who later recounted his wartime experiences in his memoir, Military Memoirs of a Confederate, noted, “our dinner was ruined…the shell passed through both walls falling into the sliced up meat and dished up vegetables and we went without dinner that day.”

Fleeing To Appomattox To Escape The War

When McLean returned to Yorkshire, he found the plantation damaged, his barn full of wounded Confederate soldiers and prisoners from the Union Army. Yet, McLean found even more ways to support the cause.

Until February of 1862, he worked for the Confederate Quartermaster, helping to ensure food supplies reached Confederate troops.

There is some evidence that McLean’s passion for the cause began to fade. Receipts show that he worked less and less for the Confederate Quartermaster. He began to charge the Confederate Army high prices for goods that he procured, leading one sergeant to complain about the, “very exorbitant prices at Manassas.”

McLean later told Alexander that he left Manassas with the hope that he’d never see another soldier.

Wilmer McLean moved his family over 100 miles south to the peaceful village of Appotomax Court House in the fall of 1863. By this time, the Second Battle of Bun Run had brought violence back to Manassas. McLean hoped to find peace further south.

Having left his plantation, he began working as a merchant-trader speculating in sugar. But Wilmer McLean could not outrun the Civil War which had consumed the nation.

As the conflict dragged toward its conclusion, soldiers — many barefoot and in ragged clothes — passed through tiny Appotomax Court House. One resident of the hamlet noted that “From the soldiers who had been passing for a day or two… we learned that there was little hope in prolonging the struggle.”

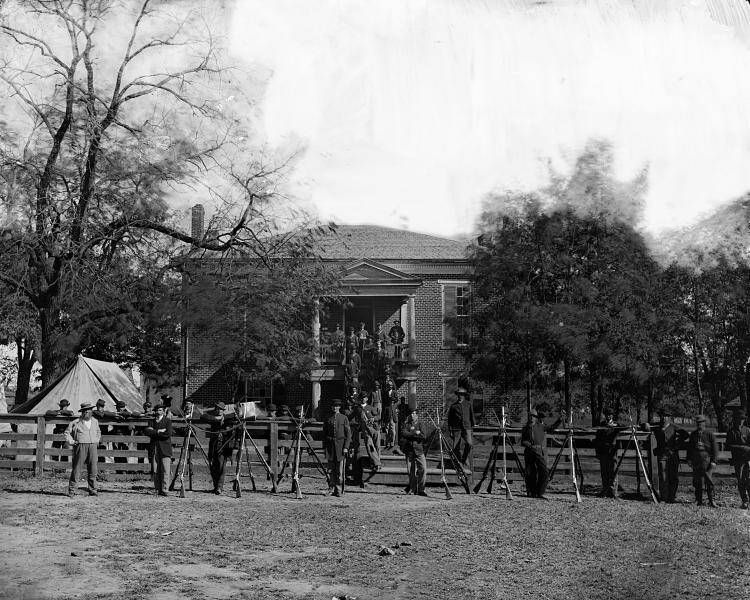

Wikimedia CommonsWilmer McLean moved to Appomattox in 1863 in hopes of avoiding the fighting.

Indeed, the hostilities between North and South had ceased. The two weary armies had set up camp near Appomattox. General Robert E. Lee sent his military secretary, Colonel Charles Marshall, to find a place for Lee and Union General Ulysses S. Grant to confer about surrender.

Marshall rode into town and asked the first white man he spotted — Wilmer McLean — for help. Marshall later recounted that McLean “took me into a house that was all dilapidated… I told him it wouldn’t do. Then [McLean] said, ‘Maybe my house will do!’ He lived in a very comfortable house, and I told him I thought that would suit.”

Marshall portrays McLean as eager to offer his home. However, other accounts have noted McLean’s reluctance to involve himself again in the war.

Wikimedia CommonsRobert E. Lee surrenders to Ulysses S. Grant at the McLean House in Appomattox. April 1865.

In McLean’s parlor, General Robert E. Lee and General Ulysses S. Grant met. Lee surrendered. After four years of violent conflict, the war that had killed 600,000 Americans had ended. Wilmer McLean stood by as a strange bookend to the bloody affair.

Though the surrender might have seemed like cause for celebration, it too damaged McLean’s property. Union soldiers took away his table and chairs where the surrender was signed and cut scraps from his sofa’s upholstery for souvenirs. One soldier even took McLean’s seven-year-old daughter’s ragdoll.

The McLean House Today

Wikimedia CommonsThe reubilt McLean House in Appomattox.

Today, Wilmer McLean holds an odd place in American history. Alexander, noting the coincidence in his memoir, wrote that McLean, “was perhaps the only man who ever had the first major pitched battle of a war fought in his front yard and the surrender signed four years later in his parlor.”

Today, the McLean farm in Manassas no longer exists. The phantoms of the Battles of Bull Run are hidden by the sprawl of urban society, although a historical marker near a CVS parking lot indicates the spot where the McLeans’ Yorkshire plantation once stood.

The Appomattox McLean House faced destruction in the years after the war. McLean, who defaulted on payment for the house, lost it to the bank. The bank sold it at public auction. From there, multiple attempts were made to dismantle the house and move it somewhere to be exhibited to the public.

It lingered in pieces until the 1940s. After a few false starts, the National Park Service opened the site to the public in 1949. Descendents of Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee cut the ceremonial ribbon in 1950, a nod to the adage that history does not repeat — but it does rhyme.

Now that you’ve read about Wilmer McLean, learn about the Confederados — Confederate loyalists who fled to Brazil after the end of the Civil War. Or, see why some states celebrate Robert E. Lee Day — on Martin Luther King Jr. Day.